Parallel runways

Boulder airport decommissioning, Area III Planning Reserve plans take off in tandem

BOULDER — At first glance, the Boulder Municipal Airport and the Area III Planning Reserve site have little in common.

One is, well, an airport. The other is a nearly 500-acre parcel of undeveloped land just north of Boulder city limits in unincorporated Boulder County.

But as momentum for a plan that would see the airport decommissioned for the purpose of building much-needed housing, the two properties have become linked.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Let’s talk about the Boulder Municipal Airport, or BDU, first, and then discuss how it relates to Area III.

Despite opposition from aviators and business groups including the Boulder Chamber, a plan to shutter the airport and use the land to subsidize the construction of below-market rate homes recently achieved a key win.

In late June, a pair of separate but complementary petitions — Repurpose Our Runways and Runways to Neighborhoods — received enough signatures to potentially appear on the November ballot.

Housing advocates, including petition organizers with Airport Neighborhood Campaign, argue that decommissioning the airport would offer a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to provide below-market housing that’s accessible to the type of middle-class worker who can’t afford a million-dollar-plus home and doesn’t qualify for traditional subsidized housing.

“The Airport Neighborhood Campaign would like to thank the voters of Boulder who signed our petitions and all of our volunteers. Because of you, residents of the city of Boulder will be able to vote this November on whether to repurpose the Boulder Municipal Airport site into new mixed-use neighborhoods with 50% affordable housing on site,” the campaign recently posted on its website.

Easing Boulder’s housing-affordability crisis — the median sales price for a single-family home in the city was nearly $1.6 million in May — is “not out of the realm of possibility — if the land is cheap,” Boulder City Councilmember Mark Wallach told BizWest in a June interview. Because the city owns the airport land, it could, in theory at least, provide parcels to developers on the cheap in exchange for a pledge to build below-market-rate homes.

Crossing your fingers and hoping that affordable housing will simply materialize based on some evolution in market conditions is “like praying to the gods for rain; you’re not going to get it. You can’t get it. The conditions are simply not possible to create this kind of housing,” Wallach said. “You can only do it if something changes in the development formula. You’re not going to get people to build the houses at minimum wage because these are professionals. You’re not going to get the banks to lend at 1% because that’s not what the market conditions provide. The only thing you can change is the cost of land, and the only way you can change the cost of land to the developer is by making it available because you are the government.”

The soonest the airport, which is tucked away on about 180 city-owned acres between neighborhoods and business parks in east Boulder, could be closed is 2042, so any new homes on the site are likely at least two decades away from welcoming their first occupants.

Still, by garnering enough signatures to put the concept of decommissioning BDU to the city’s voters, supporters of the plan took a key step forward.

Now that the petitions have been certified, the Boulder City Council has a chance to weigh in on the next steps. Here, according to the City Clerk’s office, are the potential outcomes:

- Council places the measure (closing the airport for the purpose of building homes) on the ballot as an initiated measure.

- Council proposes amendments to the measure and the committee (the groups that brought forward the petitions) agrees; it is placed on the ballot as a referred measure.

- Council decides to adopt the measure and it does not go to the ballot.

- Council decides to amend the measure and the committee does not agree with the amendments. Both measures are placed on the ballot as competing measures.

The Boulder City Council is expected to begin taking up the issue on July 25 (a hearing previously set for July 17 was rescheduled) and must provide the Boulder County Clerk and Recorder with a ballot order by early September.

While few argue that Boulder wouldn’t benefit from additional housing options for workers and families, the airport decommissioning plan doesn’t lack for critics, many of whom argue that the proposal isn’t feasible and could prove economically harmful both to businesses and city coffers.

“There seems to be a huge rush to go to the ballot before we know what the actual consequences are of decommissioning the airport,” Jonathan Singer, chamber senior director of policy programs, told BizWest in late June. “By all indications, decommissioning of the airport could be a very costly mistake that would hurt the city and our community to the tune of tens of millions of dollars over many years.”

Repurpose Our Runways “is a very dangerous ballot measure for the city of Boulder. The ballot team has offered no plan. No plan to pay for legal expenses or airport operational expenses. No legal plan. No off-ramp if things don’t go well,” Jan Burton, a pilot who flies out of BDU and a member of airport advocacy group Boulder Aviation Association, told BizWest in a July email. “It’s a gamble that could take 20 to 40 years and hundreds of millions of dollars to implement their ideas. We encourage Boulder voters to reject these ballot measures outright.“

In a statement posted to the Boulder Chamber website, the group said that “many companies and scientific institutions rely on access to the airport for their research and development activities (aside from businesses that use the airport for flight training and recreation). These companies and institutions tell us they will have to move their activities and/or businesses to other communities with the closure of the airport.”

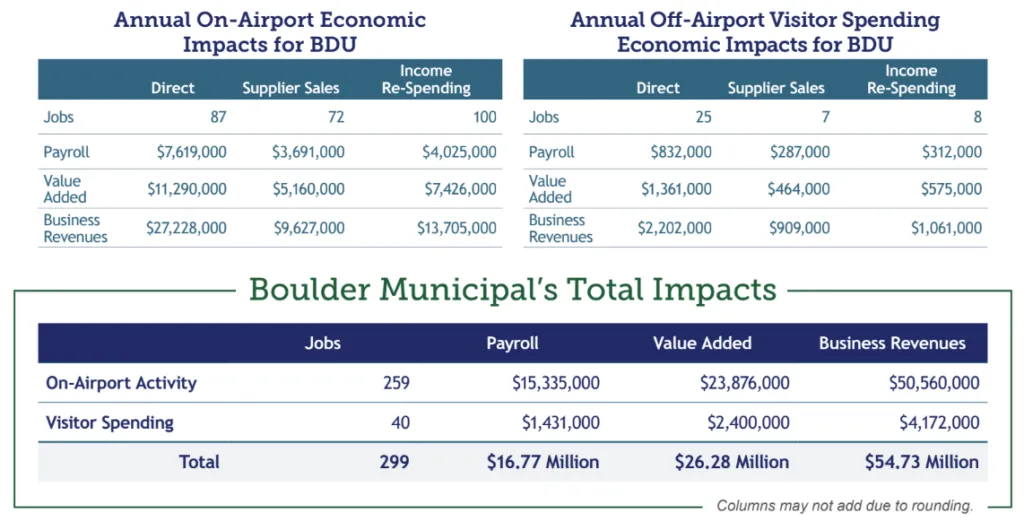

Boulder Municipal Airport, according to the Colorado Department of Transportation’s 2020 Colorado Aviation Economic Impact Study, the most recent dataset of its kind, supports 299 jobs and is responsible for nearly $97.8 million in total economic impact. That metric includes payroll, business revenues and contributions to gross regional product from both on-site businesses and visitors who travel through BDU.

Opponents of decommissioning note that the Federal Aviation Administration, which provided the city with grant funds in 1959, 1963 and 1977 to purchase a total of about 44 acres on the airport site, is unlikely to simply rubber stamp a closure. An attempt to close the airport, the say, will result in a long and expensive legal battle with the federal government.

The FAA’s “policy (is) to strengthen the national airports system and not to support the closure of public airports,” according to a letter to city staff from John Bauer, the FAA’s Denver Airports District manager. “The FAA has rarely approved an application to close a federally obligated airport. Such approvals were granted only in highly unusual circumstances where closing the airport provided a benefit to civil aviation such as funding a replacement airport in the community.”

Supporters of decommissioning counter that the FAA’s interpretation of Boulder’s obligations to the federal government is flawed and argue that a lawsuit won’t be nearly as costly as some fear.

Because the country’s airports are part of a national transportation network, even small operations such as BDU serve important functions as nodes in a wider system, Burton told BizWest in a June interview. “You can’t just pull out one airport and say that it’s not important to the network.”

As for opportunities to provide housing, the city has “other alternatives,” Burton said, “that are better than closing down an economic generator such as the airport.”

That’s where the Area III Planning Reserve enters the picture.

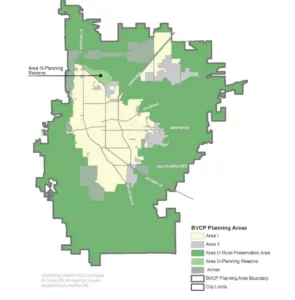

Created in 1993 with an eye toward Boulder’s future growth needs, the Area III Planning Reserve sits on 493 acres just north of U.S. Highway 36. The city owns nearly 220 acres — of that, nearly 190 acres was purchased for the purpose of building an urban park and about 30 acres were purchased with affordable housing funds — with most of the remainder held privately.

The property has been identified as potentially ripe for residential development by city officials, some of whom believe that the Area III Planning Reserve is more appropriate for such development than is the Boulder Municipal Airport site.

The Area III Planning Reserve land could “be ready for development in the next five to eight years, where we will be able to put thousands of units to meet some of our community needs,” Boulder City Councilmember Matt Benjamin said in a June interview. “That should be our focus.”

That timeline, however, could prove overly ambitious.

Boulder staffers, along with consultants from AECOM Corp. (NYSE: ACM), are currently in the preliminary stages of a service-area expansion study for Area III, but it could be years before new neighborhoods are built and residents move in.

“We would probably see nothing (built) at least until the end of the decade,” Boulder senior planner Sarah Horn told city officials during a late June update on Area III.

A service-area expansion “means making the city geographically larger by adding more area, which necessitates the provision of urban services to serve the subsequent increase in population,” Horn said. That could include water, sewer, stormwater, transportation and emergency infrastructure and services, which are currently limited or nonexistent in Area III.

Preliminary work on the service-area expansion study only contemplates the city-owned acreage in Area III, not the private land. “There will come a point where you’d definitely want to reach out (to the private-property owners) to understand their interests,” AECOM vice president Chris Brewer said.

The privately owned parcels “present a potential opportunity for future development, but also a potential constraint since they’re not controlled and owned by the city,” AECOM principal Deanna Weber said.

Wallach, who has signaled support for building homes on the airport site, said, “If we want to see a great deal of affordable and/or middle-market housing developed at this site, we’re going to need to use government-owned land to do it.”

That would mean either limiting development to only the portions of Area III already owned by the city or negotiating with the area’s private property owners to acquire more public acreage.

Preliminary work on the study, which is expected to be presented in more detail to Boulder leaders this fall, does not anticipate that large-lot, single-family homes would be built in Area III. Rather, it assumes a mix of attached-housing types with ground-floor retail and free-standing commercial spaces. The total commercial space envisioned could total as much as about 1 million square feet of neighborhood retail businesses, offices and flex buildings that could employ more than 3,000 workers.

“On the lower end, we’re anticipating approximately 4,300 housing units” and more than 9,000 residents for the city-owned acreage, Weber said. Higher-density scenarios contemplate about 6,700 homes and 14,500 residents.

“We need more housing of the right kind and we’re willing to expend considerable effort to develop new land to get it,” Boulder City Councilmember Ryan Schuchard said, but Area III isn’t the only location where housing could be built. “I would like to see as we go into future analysis additional consideration of the under-used area within the city for infill … especially parking lots and other paved surfaces where creative arrangements could be made.”

Regardless of the study’s findings, many decisions from Boulder officials and many years of additional planning from city staff and developers are likely necessary before Area III could be developed.

“It’s definitely not a foregone conclusion what we’re going to do here,” City Councilmember Lauren Folkerts said. “There is still a lot of thinking to go into this.”

At first glance, the Boulder Municipal Airport and the Area III Planning Reserve site have little in common. One is, well, an airport. The other is a nearly 500-acre parcel of undeveloped land just north of Boulder city limits in unincorporated Boulder County.