Amundson: Local events take a toll

Editor’s note: This is the fifth in what was supposed to be a series of five columns leading up to the retirement of the author. As retirement day draws closer, he determined that he wanted to write a sixth, which will appear in the June edition.

The role that journalists play in a community, providing accurate, timely, independent information cannot be overstated.

Whether it is coverage of floods or fire — the most common disaster stories we hear in this region — or something more sinister, journalists provide the first line of communication that public members often clamor to read.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Here’s one from Loveland’s history.

On Tuesday, Jan. 3, 1989, in what became known as the “Riverhouse Incident,” a former U.S. soldier who had served in Vietnam and suffered from post-traumatic syndrome got into an argument with his ex-wife west of Loveland at her home.

Wayne Strozzi, 35, reportedly physically abused her. She called 9-1-1, and he left, heading east on U.S. Highway 34, where he stopped at the Riverhouse Restaurant.

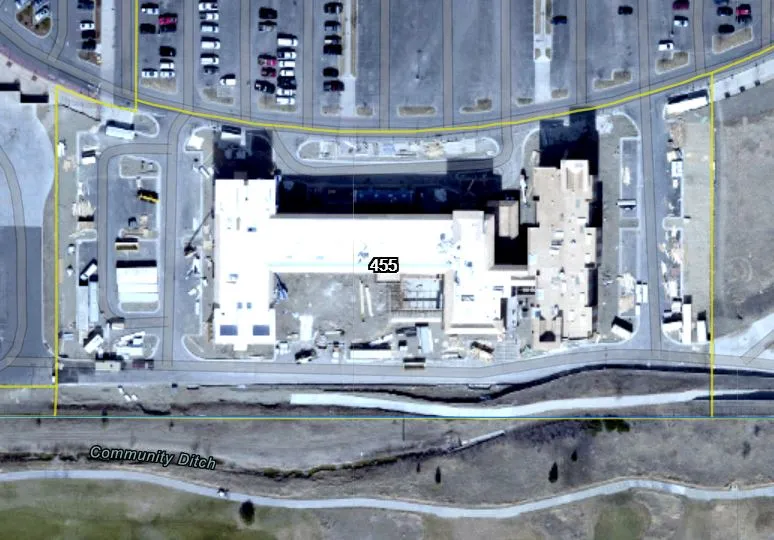

The restaurant, now a private home hidden by a cinderblock wall, was at that time a popular steakhouse. Sitting on a hill overlooking the Big Thompson River, the restaurant featured a downstairs or basement dining area popular for private gatherings. It opened to the river behind.

Upstairs was the main dining room. Bruce Copp was the owner and operator.

Strozzi entered the street-level upstairs and took about 20 patrons hostage as police began to gather.

I was managing editor of the Reporter-Herald at the time. As the newspaper owners expected, I was always connected via, at that time, pager, two-way radio, portable police scanner and, of course, land-line telephone. Company vehicles also had radios and scanners.

Lehman Communications Corp., which owned the newspaper, had invested years prior in a two-way radio system. It had base stations at the Reporter-Herald and the Longmont Times-Call and a repeater on Horsetooth Mountain that would enable coverage from Cheyenne to Stapleton Airport. Each of the newspaper’s photographers was equipped as well with all the communications gear. Each of us had call signs, and I’ve long-since forgotten mine.

Photographer Joel Radtke may have been the first to hear of the incident, but Publisher Ed Lehman also was listening in on the scanners and radios. Joel left immediately for the Riverhouse and managed to get in close before police closed off U.S. 34. He was our eyes on the scene and was sending out reports to me. Well, sort of.

Radio communication west of Loveland was spotty at best, and it turned out that Ed in Longmont could hear Joel better than I could, so Ed would relay the information to me and reporters on the outside.

The tragic night unfolded rather quickly. Strozzi made demands, police set up a command post outside, and one of their number climbed with a sniper rifle onto the bluff across U.S. 34 and above the restaurant to the north.

Police were able to evacuate the patrons in the private party on the lower level and sent them to a nearby home for shelter.

But those on the upper level were trapped and panicked, as you might imagine.

As detailed in a massive post-incident report — a paper copy was 12 to 18 inches thick — the sniper was given the go-ahead to shoot if he had a shot, and he did. Strozzi was hit in the chest. As he fell, he shot hostage Sally Mills, 40, who died at the scene.

Customer Fenton Crookshank, the general manager of Deines Lumber Co., jumped out a bathroom window. Another police officer mistook him for Strozzi, fired and killed him.

Strozzi, it was later determined, shot himself after killing Mills.

He was still alive at that point, and Joel captured a photograph of him being taken out on a stretcher. He later died at McKee Medical Center.

All the details were not available until months later after the investigations concluded, but the R-H had the immediate details that the community was desperate to hear. The story was picked up across the country with the New York Times and Washington Post among those that carried a report.

Our story also had that photograph, which I opted to publish.

It was generally our policy at the time not to publish pictures of dead people. In this case, because Strozzi was alive at the time the photo was taken (but not at the time of publication) and because of the severity of the situation, I opted to publish.

That decision was not without consequences. Strozzi’s daughters called me the next day to complain. They were high-school aged and extremely well spoken. And angry. They left me with some regret.

We had other photos but none that told the story better. Still, I sometimes still question that decision.

Such situations are more common in newsrooms than many might believe. In community journalism, the reporter or editor or photographer might have personal knowledge and personal connections that make telling the story difficult.

Here’s another story, which I still consider to be the most personally impactful of my career and one that I hesitated to place in this column, because the story remains raw to me and to the families and friends of the story’s subject, who still live in the community.

It was Monday, April 16, 1996, and reporter Sara Quale returned to the Reporter-Herald newsroom from her city hall beat to say that someone, a police officer, was found dead in his office. She said he was a captain.

There were only two captains at that time, and one of them was a close friend to many of us and universally well-liked. Captain Dave Davison had committed suicide with his service weapon in his office at the police department, leaving behind a grieving family, just days before the birth of his first grandchild.

I was the president of the Kiwanis Club that year, and Dave was on the board. He attended the club board meeting just days before. He had also been president the year I joined, a fellow softball player, an active participant in everything we did as a club. He was Mr. Kiwanis.

I called each of the 50 club members to tell them of what had happened. The club helped at his funeral, which was the largest funeral I’ve ever attended. Police officers came from every corner of the state, of course.

His widow, Lana, played Celine Dion’s “Because You Loved Me” at the service, the first time I had heard that piece and one that brings back that day every time I hear it.

Dave left three letters, none of which were made public, although at least one made its way into court documents later; none, I’m told, provided an answer to the question we all had although he did make reference to depression and stress. We did the best we could to tell the story, to help a grieving community.

The Kiwanis Club at the time had arranged for Tom Sutherland, the Colorado State University college professor who had until just prior to this been held captive in Lebanon, to give a program the following Saturday night. I had contacted former Associated Press reporter Terry Anderson, who had been held with Sutherland, for introductory material. (Anderson died in April this year, also bringing back memories of this time.)

I called Sutherland to cancel the event, but he encouraged me not to. “I have something that will be helpful,” he told me.

You see, Sutherland had attempted suicide while in captivity but didn’t complete the act. He wanted to share his story of desperation and despair and how he overcame it.

Prior to coming to BizWest, I worked for a couple of years with my good friend Richard Ballantine, the publisher of the Durango Herald. Richard had a philosophy that newspapers ought to report suicides the same way it reports other deaths, including citing suicide as the cause of death in obituaries when the information could be found. While most newspapers report on suicides only if they happen in a public place, Richard believed that the stigma attached to suicide needed to be broken down because ultimately mental illness and behavioral health are root factors when they occur. Those things need to be addressed and understood.

I learned through a recently published biography on the Ballantine family that Richard’s birth father, Richard Gale, committed suicide after returning from World War II — a likely result of what we now call Post Traumatic Syndrome. Richard Ballantine was just six months old at the time.

Why tell this story? Well, it’s the nature of what it means to be a community journalist. Events can’t be controlled; they need to be reported; and they take an emotional toll along the way.

Not as severe a toll as those experienced by family members, of course, but a toll nonetheless.

Kari Wall, Dave Davison’s daughter, founded the Dave Davison Foundation seven years ago. Each June, the foundation conducts a craft and car show in the parking lot of the Cactus Grill to raise awareness about mental health.

Read Ken’s previously published columns from this series.

Truth: Stranger than fiction

https://bizwest.com/2024/01/05/truth-stranger-than-fiction/

Collaborative journalism: A joint effort to protect a community

https://bizwest.com/2024/02/02/collaborative-journalism-a-joint-effort-to-protect-a-community/

Amundson: Not always what it seems

https://bizwest.com/2024/03/08/amundson-not-always-what-it-seems/

Amundson: Stories some don’t want told

https://bizwest.com/2024/04/02/amundson-stories-some-dont-want-told/

Amundson: Local events take a toll

https://bizwest.com/2024/05/03/amundson-local-events-take-a-toll/

Amundson: Career focused on community journalism

https://bizwest.com/2024/05/30/amundson-career-focused-on-community-journalism/

Amundson to retire from BizWest after 51 years in journalism

https://bizwest.com/2024/05/31/amundson-to-retire-from-bizwest-after-51-years-in-journalism/

The role that journalists play in a community, providing accurate, timely, independent information cannot be overstated. Here’s one from Loveland’s history.