Measuring impact of alternative work

Challenge remains with emergence of the gig economy

Technological advances combined with shifts in the way Americans view work and employment have bolstered a narrative that would suggest nearly everyone is supplementing their income — or making their entire living — driving for Uber.

While millions of Americans are indeed working in nontraditional jobs, measuring the size and impact of the alternative or gig economy remains a challenge for economists.

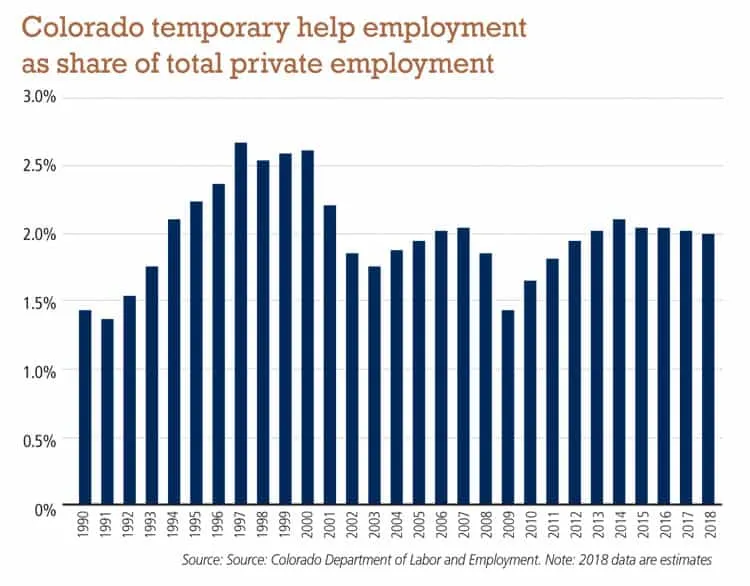

Workers in temporary help services industries — defined by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics as “establishments primarily engaged in supplying workers to clients’ businesses for limited periods of time…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!