Closing the Boulder Municipal Airport: Flight of fancy or city’s best option for housing?

Proposal ignites dogfight over airport’s future

BOULDER — Boulder is a great place to live — just ask U.S. News & World Report.

But Boulder can be a difficult place to live. And for many, this beautiful city where the median sales price for a home has exceeded $1 million for nearly this entire decade, is an impossible place to live.

What if Boulder leaders decided to roll the dice on an uncertain gambit to secure for Boulder’s Regular Joes and Janes the chance to buy a quality home at a fraction of that price?

SPONSORED CONTENT

What if that roll of the dice meant closing the Boulder Municipal Airport? Fighting the federal government? Losing millions of dollars in funding, shrinking sales-tax deposits into city coffers and shedding local jobs?

Those, the parties involved in a brewing dogfight over the future of the airport argue, are the stakes.

Runways or driveways?

A pair of separate but complementary petitions — Repurpose Our Runways and Runways to Neighborhoods — would ask voters to approve a plan to decommission the Boulder Municipal Airport, or BDU, and use the land to build homes. They recently received more than 8,000 (yet-to-be-certified by the Boulder City Clerk’s office) signatures between the two.

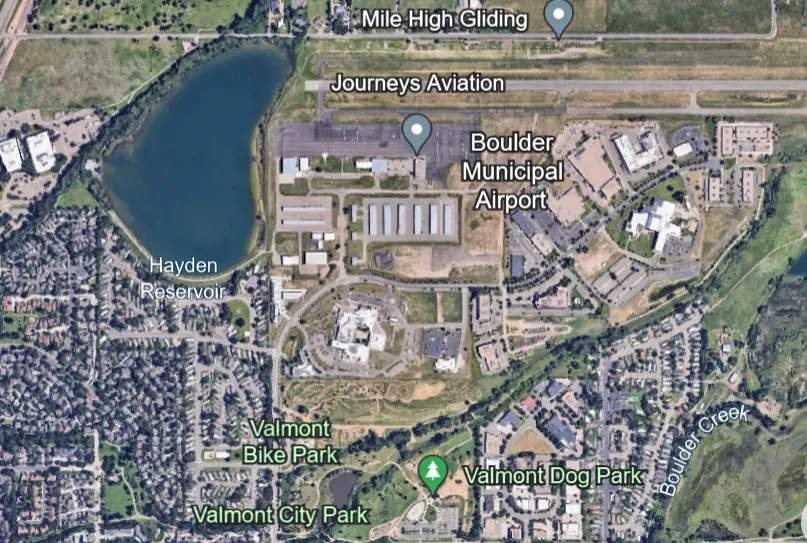

The soonest the airport, which is tucked away on about 180 city-owned acres between neighborhoods and business parks in east Boulder, could be closed is 2042, so any new homes on the site are likely at least two decades away from welcoming their first occupants.

“The city of Boulder is at a crossroads. We have an opportunity right now to re-examine land use at the airport site,” the Airport Neighborhood campaign, which supports both petitions, urges on its website. “We need to seize this moment to reconsider how these 179 acres of public land can best contribute to the Boulder of the future. Now is the time to reach the voters of Boulder with a vision of new neighborhoods that are affordable to our families, nurses, teachers, fire-fighters, police officers, day care workers, elder care workers, and other essential workers and service workers.”

While there are certainly critics, the concept of the city decommissioning BDU and selling the land at below-market rates to developers who would pledge to build “missing-middle” housing — homes for workers who wouldn’t qualify for government housing subsidies, but can’t afford entry-level market-rate units — has caught on with some Boulder officials, and the idea is being evaluated by city staff.

“We’re never going to get $399,000 starter homes again. You used to be able to do that at Table Mesa, but those days are gone. But the possibility of $499,000 or $599,000 townhouse or home is not out of the realm of possibility — if the land is cheap,” Boulder City Councilmember Mark Wallach told BizWest.

Crossing your fingers and hoping that affordable housing will simply materialize based on some evolution in market conditions is “like praying to the gods for rain; you’re not going to get it. You can’t get it. The conditions are simply not possible to create this kind of housing,” Wallach said. “You can only do it if something changes in the development formula. You’re not going to get people to build the houses at minimum wage because these are professionals. You’re not going to get the banks to lend at 1% because that’s not what the market conditions provide. The only thing you can change is the cost of land, and the only way you can change the cost of land to the developer is by making it available because you are the government.”

City officials “will discuss the future of the airport” during a Boulder City Council meeting set for July 18, Boulder communications program manager Aisha Ozaslan told BizWest in an email.

“Community members are entitled to petition the city of Boulder as part of their democratic rights, and we are aware of ongoing petitions related to the Boulder Municipal Airport,” she said. “We value community input and recognize the community’s interest in the airport, as well as the various sentiments, hopes and visions the community has for the future of the airport site.”

Possibility or pipedream?

If Boulder officials and voters decide that there was consensus support for closing the airport, would such a move even be possible? It depends on whom you ask, but most agree that it would mean picking a fight with the Federal Aviation Administration.

“The FAA has written multiple letters to the city and have made it pretty clear” that the agency is not on board with decommissioning the airport, Boulder City Councilmember Matt Benjamin said. “… Is the community really prepared to get into a long-term, protracted legal battle with the federal government?”

The agency’s “policy (is) to strengthen the national airports system and not to support the closure of public airports,” according to a letter to city staff from John Bauer, the FAA’s Denver Airports District manager. “The FAA has rarely approved an application to close a federally obligated airport. Such approvals were granted only in highly unusual circumstances where closing the airport provided a benefit to civil aviation such as funding a replacement airport in the community.”

Because the country’s airports are part of a national transportation network, even small operations such as BDU serve important functions as nodes in a wider system, said Jan Burton, a pilot who flies out of BDU and a member of Boulder Aviation Association, an airport advocacy group. “You can’t just pull out one airport and say that it’s not important to the network.”

Portions of the BDU site — about 44 acres — were acquired with federal grant funds in 1959, 1963 and 1977, and “grant assurances associated with land purchased with federal aid do not expire and the land must be used in perpetuity for its originally intended purpose.”

But, Wallach said, there’s a catch: This regulatory policy was adopted by the agency years after those three land acquisitions.

“The FAA is an advocacy organization for the pilots. Their position, as I can understand it, is that they can retroactively author those covenants to provide that we must operate (the airport) in perpetuity. …The FAA doesn’t like to recognize it, the pilots don’t like to recognize it, but those covenants are dead,” he said.

If the city were to decide to decommission the airport, the FAA’s position is that it must reimburse the federal government at “fair market value” for the land Boulder acquired with federal grants. On the open market, land in Boulder often fetches more than $1 million per acre.

“It’s not a question of appraising the land and having to pay that money. The covenants say that in the event we don’t want to use it as an airport, we have to sell the land at its highest and best use, well, at its market value. Which leads me to believe that it can be market value at whatever we choose to zone it,” Wallach said. In other words, if the city zoned the property in such a way as to require developers to build below-market homes, the land itself would be valued below the market rate, significantly lowering the reimbursement total the city would owe the federal government.

“In the worst-case scenario, we would sell the (44 acres acquired with federal grants to developers), we would pay the feds, (developers) would build (market-rate) housing and we would get tens of millions of dollars for our inclusionary housing fund or 25% onsite affordable housing,” Wallach said.

The remainder of the site would be “free and clear” for the city to build “housing for which we can’t produce and there are no subsidies to produce, unless the subsidy comes in the form of the land,” he said.

Others disagree with the decommissioning proponents’ assessment of the situation. Burton said closing the airport could represent a “potentially $200 million boondoggle” for the city and its taxpayers.

“Let’s not forget the fiscal side of this, which we have to be very concerned about,” Benjamin said. “My colleagues on City Council and members of our community should really take into account the sobering news that our fiscal projections are not great over the next couple of years when we could see stagnating or declining revenue. Even if we were, let’s just say tomorrow, to prevail and sever our ties with the FAA and reclaim that property, we would still have to operate an airport for 18 years and cover all of those expenses.”

If the city was on the hook for millions of dollars in airport expenses now paid by the federal government, “we cannot do the other things that our community is asking us to do.”

‘Valuable resource’

Even if the BDU were to close and the city was not responsible for millions of dollars in reimbursement payments, Boulder would be losing its airport along with the businesses and jobs that rely on it.

Would those losses be worth it if hundreds of new homes could be built? Again, it depends on whom you ask.

The airport is a “valuable resource that serves an immense number of local businesses,” Benjamin said.

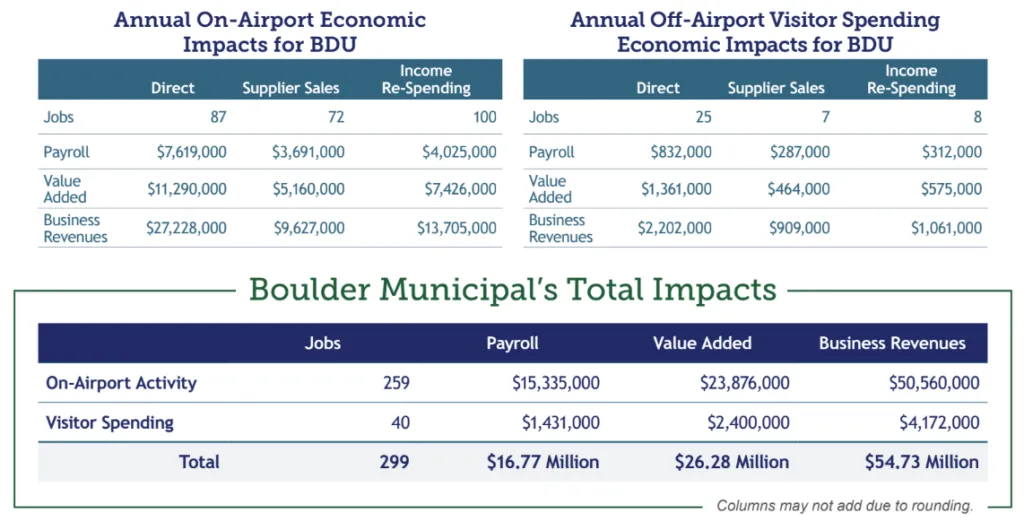

Boulder Municipal Airport, according to the Colorado Department of Transportation’s 2020 Colorado Aviation Economic Impact Study, the most recent dataset of its kind, supports 299 jobs and is responsible for nearly $97.8 million in total economic impact. That metric includes payroll, business revenues and contributions to gross regional product from both on-site businesses and visitors who travel through BDU.

“Each individual airport contributes to the statewide economic impacts that result from on- and off-airport activities. In addition to the on-airport and visitor components, the state benefits from the activity that is generated as a result of air cargo,” the CDLE study said. “These statewide benefits represent aviation’s economic contribution to Colorado’s economy. Beyond these quantifiable impacts, there are many more health, safety, and mobility benefits that are experienced due to airport activity.”

The local business community has “concerns that we think are important to consider from a business and economic perspective,” Boulder Chamber president and CEO John Tayer said. Chamber officials “are now working toward a formal position” on the decommissioning issue.

In addition to the economic considerations, the airport plays an important public-safety role in the community, its defenders say.

The Army Corps of Engineers “used Boulder Airport to rescue people from the mountains over and over” during the devastating flooding in 2013, said Burton, who is a former Boulder City Councilmember in addition to being a pilot. “It’s also the location of Boulder’s MedEvac” operation, which flies patients to hospitals around the region. “That’s an important community aspect.”

The Boulder Municipal Airport could play a role in next-generation, clean-air travel for commuters and in the evolution of drone transit for goods and materials, Tayer said. “We might look back at closing the airport as something that limits us in terms of access to the center of the community for those kinds of services.”

An alternative site for housing?

Opponents of decommissioning the airport point to the Area III Planning Reserve, a vacant 500-acre parcel in Boulder County just north of Boulder city limits, as a more-appropriate location for residential development.

With an eye toward potentially annexing the property, Boulder staffers, according to a city memo, are conducting a study of the area “to help the community and decision-makers understand the scope and extent of providing city services to this area and weigh the potential costs and benefits of expanding services here for future generations.”

The city has “other alternatives,” Burton said, “that are better than closing down an economic generator such as the airport.”

The Area III Planning Reserve land could “be ready for development in the next five to eight years, where we will be able to put thousands of units to meet some of our community needs,” Benjamin said. “That should be our focus.”

Throughout the city, “there are great opportunities for further infill development and for the development of Area III that we want to partner on,” Tayer said. “Let’s work together on those opportunities. If we look down the road and realize that those don’t meet our needs, we could revisit this decommissioning proposal.”

To “whimsically” decide to close the airport would be “shortsighted,” Benjamin said.

“I’ve never heard of an airport reopening. If we were to close it, it’s gone and it doesn’t come back.”

A pair of separate but complementary petitions — Repurpose Our Runways and Runways to Neighborhoods — would ask voters to approve a plan to decommission the Boulder Municipal Airport and use the land to build homes.