Let me go naturally

Green burial, water cremation, body composting offer alternative exit options

In the group Blood, Sweat & Tears’ 1968 hit song “And When I Die,” David Clayton Thomas sings, “All I ask of dying is to go naturally.”

The Grammy-winning Canadian vocalist is alive and well at 81. But if he would come to Northern Colorado or the Boulder Valley when his time is nigh, he might just get his wish — courtesy of businesses such as Goes Funeral Home in Fort Collins or The Natural Funeral in Lafayette.

Colorado for the better part of the past century has been a mecca of environmental consciousness and innovation, so it seems only natural that it would move beyond greener energy, foods and medications — and into the beyond itself. After all, studies have shown that traditional coffin burials and flame cremations aren’t the most environmentally friendly of procedures.

SPONSORED CONTENT

According to recent research by scientist Mary Woodsen at Cornell University, the $16 billion U.S. funeral industry conducts traditional burials by using 4.3 million gallons of embalming fluids per year, including about 827,060 gallons of formaldehyde, methanol and benzene, as well as about 1.6 million tons of concrete for vaults, 90,000 tons of steel and 20 million board feet of casket wood — enough to build about 1,600 homes. Those caskets and vaults, she found, leach iron, copper, lead, zinc and cobalt into soils.

Conventional flame cremations, she found, pump between one and six grams of mercury into the atmosphere, depending on how many implants or fillings the deceased had.

Instead, some families are choosing a greener way for their loved ones to return to the earth.

In the town of Crestone in Saguache County, the departed can be consumed in the nation’s only open-air public cremation pyre. In Fremont County, meanwhile, families can bury their loved ones as they are — wrapped in a biodegradable shroud with no embalming fluids, caskets or vaults – at the Colorado Burial Preserve in the hills near Florence.

“It’s just going back to the earth, like many, many people around the world do,” said Stephanie Goes, who co-owns Goes Funeral Home along with her husband, Chris. “They don’t do all the things we do in this country.”

Stephanie Goes liked the idea so much that she worked with the city of Fort Collins to create the Garden of Harmony, a section of Roselawn Cemetery where such burials could take place.

“It’s considered a hybrid cemetery because there’s traditional graves and burials with vaults and caskets, and then there’s a green section,” she said. “We tried to get something more on the lines of a conservation burial ground, but the city was not willing to go in that direction. So what we were able to get was this section. In time, maybe we’ll get something like Soapstone Prairie, that type of natural area where you’re a little bit more in nature than next to a regular cemetery. That was my original goal, but I had to step back from that and allow the city to decide they would go with this, not what I originally proposed.”

Added Ren Scherling, Goes Funeral Home’s general manager, “Something like the Colorado Burial Preserve, but so you don’t have to drive all the way to Florence.”

Roselawn is certified with the Green Burial Council, which has been working since 2005 to make burial sustainable for the planet, meaningful for families and economically viable for providers. The town of Wellington also maintains a natural cemetery with no vault requirements, but it’s not certified with the council.

“If you have a large-enough piece of land and you have a location properly selected regarding your neighbor’s property, you can do it on that private land too,” she said. “But it has to be outside city limits. The cities will not allow you to do this on land inside the city limits.”

The Goes family and Seth Viddal, co-owner and CEO of The Natural Funeral, also have added different green options that are more elaborate, time-consuming and expensive — but in the end leave survivors with some tangible and useful keepsakes. Both offer alkaline hydrolysis — more commonly known as “water cremation” — and Viddal also has introduced natural organic reduction — known as “body composting.”

Viddal explained the difference simply: “Water cremation is a process of chemistry,” he said. “Natural reduction is a process of biology.”

Water cremation can trace its roots to 1888, when the process was patented by British farmer Amos Herbert Hobson as a method to process livestock carcasses into plant food.

Colorado legalized the process in 2011 when the Legislature changed the definition of cremation.

“It’s legal in 28 states, including two states that we border that I’ve worked in before, Wyoming and Kansas, where it’s been legal for a long time,” Scherling said, “but there are no active facilities there, no active funeral homes that have a unit onsite like we do.”

Chris Goes said he first heard about it about eight years ago.

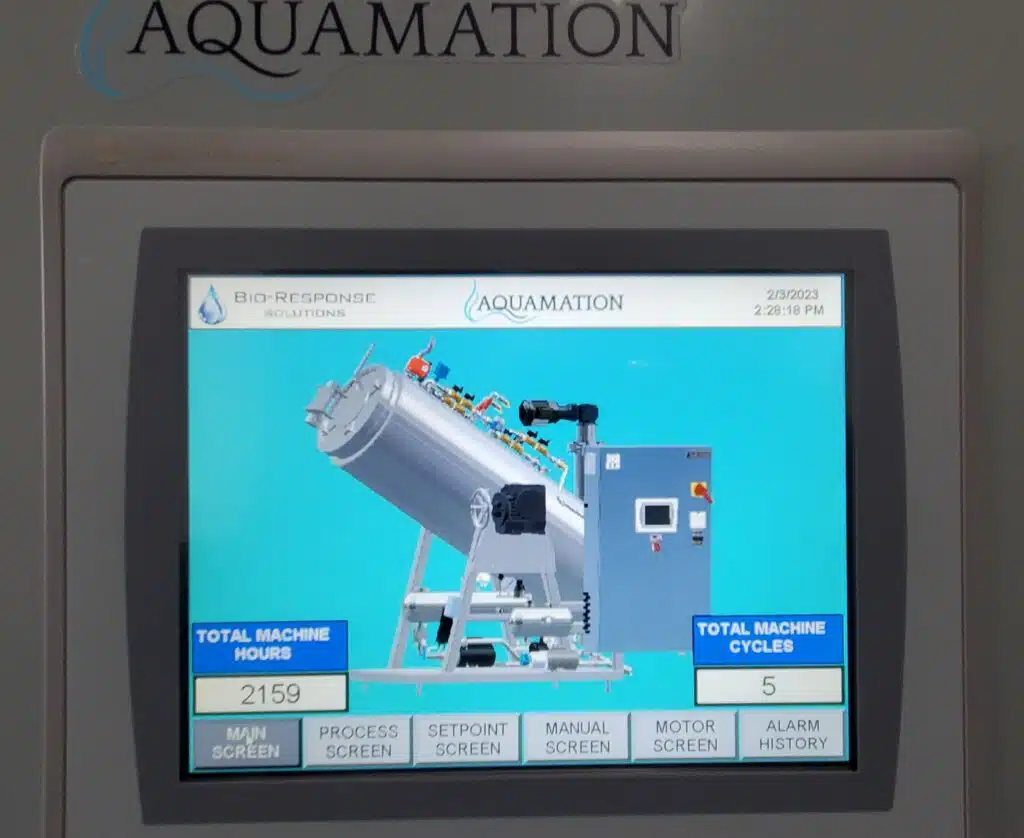

“It took me four years to study it and make sure it was something I would be comfortable with offering to the public,” he said. “Its green nature is what really pushed me over the edge. About three years ago, we finally made the decision to do it, and it’s taken this long — we’ve only had it offered since Dec. 1.”

Goes did two water cremations in December, two in January and one so far in February.

“One of the reasons I became so gung-ho about water cremation was cost,” Chris Goes said. “Regular casket burial could be $6,000, $8,000, $10,000. Green burial comes down to maybe $5,000. Water cremation is $3,200. Some people say ‘I love the idea of a green burial but I can’t afford it.’”

He said statistics show 60.5% of families are interested in exploring green funeral options because of their potential environmental benefits, cost savings or some other reason — up 6 percentage points from 2021.

The National Funeral Directors Association 2022 Consumer Awareness and Preferences Report showed that 57.5% of families nationally would choose one form of cremation over a traditional burial, compared with 36.6% for traditional burial.

“At the beginning of my career in 1982, maybe 5% of the folks we helped preferred cremation,” Chris Goes said. “Here in Northern Colorado, it’s now 80%, 85% for cremation instead of burial.”

He cited Colorado’s environmental consciousness as a large part of the reason.

Natural gas is used in traditional flame cremations, he said, and the process lasts around three hours, whereas with water cremation, “using that kind of energy is what we’re avoiding. Less energy in, less output.”

Flame cremation emits mercury and other gases into the atmosphere, Scherling added. “With water cremation, depending on the higher or lower temperature setting, we’re reducing not only the emissions but the overall process anywhere between 70% and 90%.”

Chris Goes, whose family owned a funeral home in New Jersey, opened the Fort Collins mortuary 26 years ago “with Stephanie’s blessing and my heritage.”

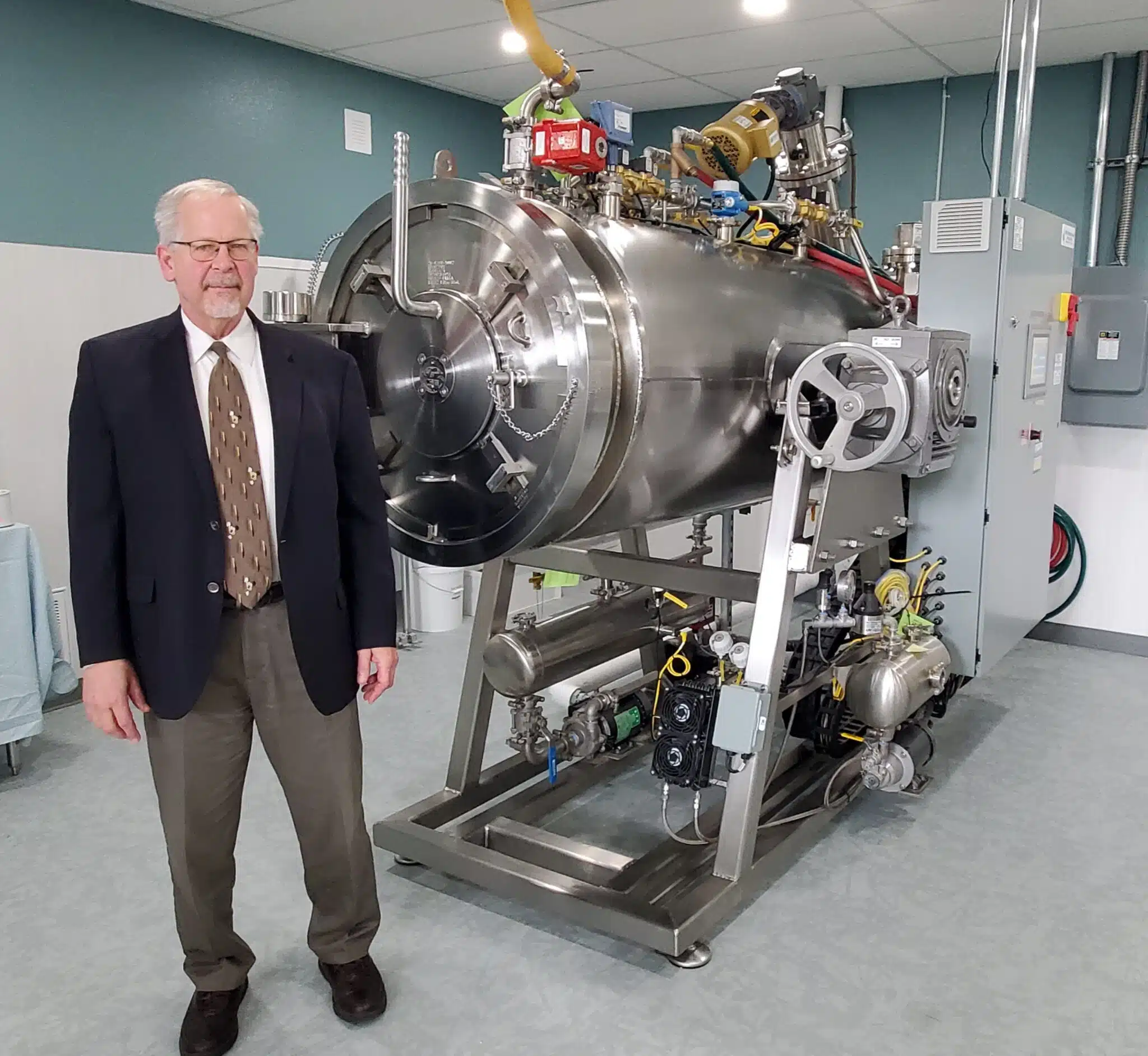

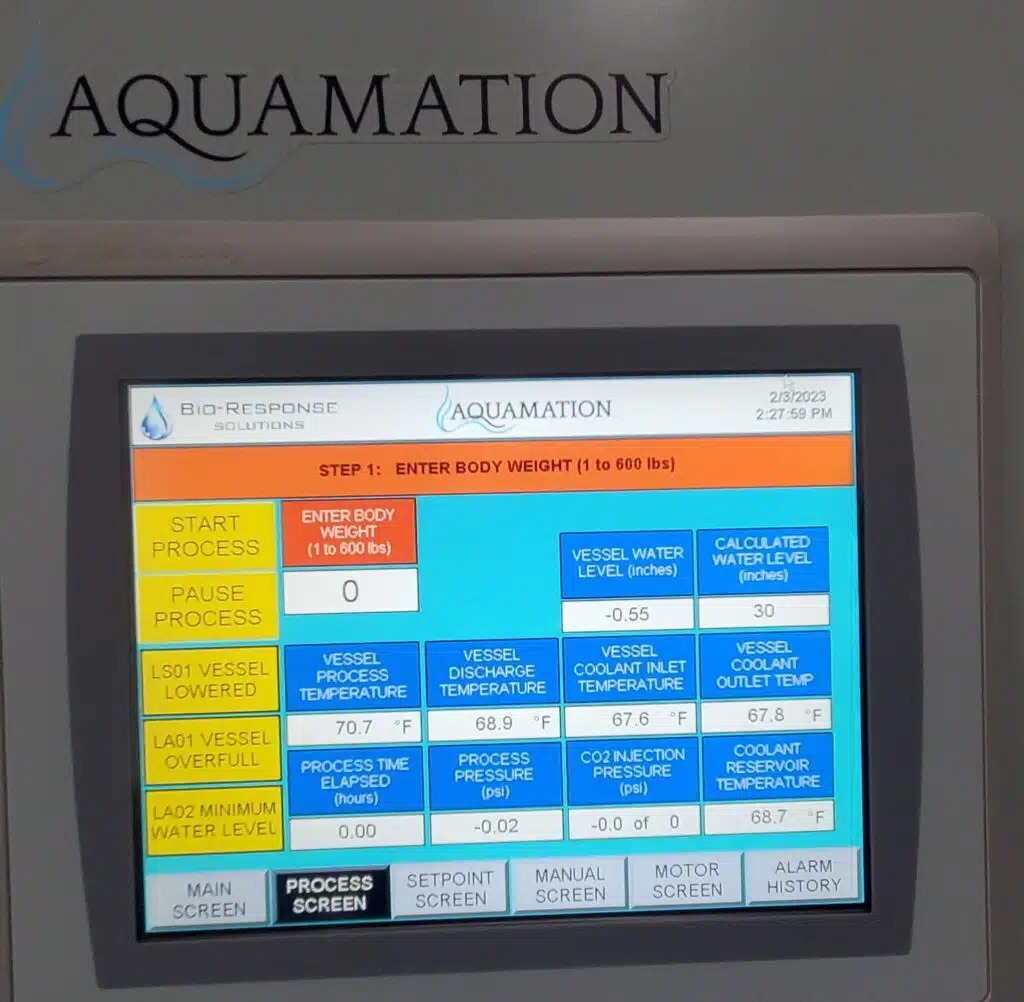

They liken the process to natural decomposition, but with a technology that speeds up the process using heated water, potassium hydroxide and the same alkali components found in the soil. At Goes, a body is placed into a rounded stainless-steel chamber in an Aquamation machine built by Bio-Response Solutions, based in Indiana — a state where the process is not yet legal. That company designed, sold and installed the first single-cadaver alkaline hydrolysis system in 2005 at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

The process, Scherling said, requires “time, temperature and turbulence.” The time can range from six to as much as 14 hours, he said, depending on the size of the person and the water temperature used, which can range from 170 to 212 degrees – as opposed to the 1,600- to 1,900-degree heat needed for flame cremation. The turbulence the machine creates, he said, is “the physical agitation that needs to happen in order to make sure every inch, every fiber is treated accordingly, so the process can be successfully completed and finalized.”

Through this process, any trace of DNA is removed and a person’s body is reduced to fragments of bone, which are gently pulverized into an ash-like substance — whiter in color and more powdery in consistency than the actual ash created by flame cremation — and are then returned to the family in an urn of their choosing.

The residual water used in the process is “treated with CO2 to adjust the PH level, and then it’s safe to go back into the system” as effluent, Scherling said.

Officials at Fort Collins’ Boxelder Water Treatment Plant “have been very thorough and worked with us on the whole process,” Chris Goes said. “Three years ago, before we were ready to actually do this, we thought we’d better check with them. Back then, they were fine with it, but now they’re really scrutinizing it closer. In fact, I just got more approvals, the signed agreement from Boxelder. We had permission to start, but they wanted to make sure they could test the effluent to make sure it is what we told them it was or what we were told would be going into the system.

“We were not going to put a deposit on the equipment until we knew that Boxelder was going to approve this process. So they checked it left and right, stem to stern. Now they’re saying OK, now we want to really see where the rubber hits the road, that the actual effluent is what we’re told it is. They’re very happy with it.”

Not all that water ends up as effluent. Sometimes, families want some of it.

“The families request it like anything else,” Scherling said. “As easy as we can receive a lock of hair or obtain a fingerprint or a handprint, we can certainly set aside whatever a family wants.”

Stephanie Goes said those families receive the water “in little 12-ounce mason jars. One family wanted 12 of them. We tell them you don’t pour it right on your plants; you have to dilute it one part to 10. You have to mix it with warm water to make sure it’s best for your plants.”

Whereas a body can remain clothed for flame cremation, Scherling said, “we can’t do that with water cremation” because, as Stephanie Goes explained, “Otherwise, they don’t break down in the machine.”

“Anything like cotton or polyester or synthetic materials have to be removed prior to the process taking place,” Scherling said. “We do have silk shrouds, silk body bags that can accommodate and naturally break down during that process — whether it’s silk or a few select materials that are from a different strand of proteins.

“We’re left with bone fragments and what I call surgical metal: rods, pins, screws, artificial hips, knees, elbows, shoulders, pacemakers, etc. That is what we separate before we place cremated remains into an urn.”

With flame cremation, Chris Goes said, those artificial items “survive and come out charred. With water cremation, they come out pretty and shiny. They survive the process.”

Generally, those items get recycled, but some families want them back.

“It’s usually the 8- or 10-year-old boy who says ‘I want that from grandpa,’” Chris Goes said, and Scherling added that “family members make them into anything from wind chimes to ornaments to artwork. These are not hypotheticals; these are actual requests — and it’s not my position to tell you what you should do with it.”

Goes Funeral Home charges around $2,180 for flame cremation and $3,180 for water cremation, Scherling said. It performs about 30 flame cremations a month.

“We are still going to continue to offer flame cremation, because this particular process, just like any process, everybody has their own thoughts about it,” Stephanie Goes said. “They may not like the water part, they may like the flame part. We’re not going to replace our flame crematory with this, but what I would hope is that we can reduce the amount of cremations we’re using in our flame crematory because that essentially helps our environment. We’ve had a lot of cremations during the COVID time, and it’s put a great strain on our crematory. This will actually kind of help that.”

Some opposition to water cremation has been on religious grounds. The Catholic Church in the United States has opposed both water cremation and body composting, contending that the processes don’t “treat the body with respect.” And Scherling noted that some Hawaiians believe even bones still possess a spirit.

Most of the reservations Chris Goes has heard, however, center on the fact that “it’s new, it’s foreign. They’re not used to it. But honestly, 50 or 60 years ago, flame cremation was new. Now, most people use cremation in some form or another.”

As yet, only two other facilities in Colorado offer water cremation. One is called Be a Tree Cremation in Denver, where, Stephanie Goes said, the owner “takes the effluent and gives it to people at home. She works with a nursery to have a tree planted in memory of their loved ones, they use the water to nourish it.”

The other is The Natural Funeral in Lafayette, where Viddal also is the state’s only provider of natural organic reduction — a human-composting process approved by the Legislature in 2021. He plans to open a second location on March 1 at 1440 Boise Ave. in Loveland, the former location of Viegut Funeral Home.

“The law was passed Sept. 7, and we processed our first person on Sept. 21,” Viddal said. “We had already built our first vessel in anticipation of this becoming law.” That first body, he said, was “a 19-year-old young man who died in an accident. We told his family, ‘If you’ll trust us with your son, we’ll shepherd him through this process.’”

He calls the vessel a “chrysalis.” The first one was built of plain wood, he said, but “with the new vessel, we’ve beautified the exterior. The new vessel is constructed out of reclaimed beetle-killed pine wood.

“This is not yard composting where we’re adding leaves in a pile in the woods,” he said. “We surround the body in the vessel with bulking agents — wood chips, straw and alfalfa — in order to complete this transformation.”

The hermetically sealed vessel is rounded on either end so it can be periodically rotated.

“We created the interior to have a pod that is removable,” he said. “Using a lift, I can pull the pod out.”

The vessel is monitored for oxygen, temperature and moisture content. “When the computer says it’s time to roll the vessel, we put it where we can roll it.”

The temperature inside the chrysalis is “always fluctuating,” Viddal said. “It’s room temperature to start. When we close that lid, it raises the temperature about 10 degrees a day. By three days, it’s 100, and by 10 days it’s 150 to 160 degrees. Regulations say the interior temperature must reach 131 degrees and remain there for 72 straight hours. We run each vessel through three heat cycles, and as soon as it goes under 130, we roll it.”

That rolling, he said, “excites the microbes, and they find new matter to biologically process. They reposition themselves, and the temperature rises.”

Depending on the size of the person, the process can take anywhere from 2½ to six months, he said. “We test the soil for stability, lack of pathogens and maturity of the compost, and at that time we know it’s ready to return to the family. You hand a wife or a parent back the living soil, and it is a special moment.”

A 200-pound body inserted into the chrysalis would be packed with four times its weight in the bulking agents, he said, “but a lot of that is moisture — 60% of a body — that’s going to evaporate. At the end, that’s going to be about 600 pounds of soil — no pathogens, no human DNA, only soil.”

The family might receive up to 16 bags of what Viddal calls “living soil.”

“It’s a way to gift their body back to the earth that’s very meaningful to them,” he said. “They can use it on rose bushes, oak trees or their flower gardens. About half the families take the soil back and use it in their own gardens, but some families donate it to animal sanctuaries or flower farms.

“I would love to come back in the form of bouquets,” he said.

Regulations passed by the state prohibit the use of the human compost on edible food crops, however. “The state, for health reasons, recommends using it on ornamental trees, flowers and grasses,” Viddal said, “but not on a crop you intend to consume.”

When a body goes into the vessel, he said, “we call that a laying in. When we take that out, we call that a laying out. We provided our 50th laying-in service last week.”

The process costs around $7,900, he said, including the managed biological process, transportation, the death certificate and returning the soil to the family.

The most opposition Viddal encountered was in 2018 when he wanted to open the facility in downtown Lafayette and neighbors complained to the City Council that it would be “unsettling” to have “hearses” and “dead bodies” near restaurants, ice cream stores and brewpubs — even though Blunt Mortuary has existed for many decades in Colorado Springs’ touristy Old Colorado City district.

“This process is radically new,” Viddal said. “It’s only legal in six states, and there are only options in two of them” — including Washington, which was the first to legalize it in 2019.

To educate lawmakers and potential customers about the process, Viddal is part of a group that has formed the National Organic Reduction Association, which will hold a conference March 16-17 in downtown Denver to “tell the story of who’s doing it, how to prepare, the cost and how much the family is involved,” Viddal said. “We’ll bring together the scientific and academic community to explain that this is safe and it works.”

From that conference, Viddal and others will head to Estes Park for Frozen Dead Guy Days, a festival born from the story of Bredo Morstoel, a Norwegian man who was cryogenically frozen and stored in a Tuff-Shed above Nederland in hopes that someday the technology would be developed to revive him. The Natural Funeral is a co-sponsor of the event, and Viddal said he has even offered to transport Morstoel’s body to Estes Park.

“I hear about cryogenic freezing periodically, but it’s not available in my world,” Chris Goes said. “Sending people into outer space for their final disposition could be next. Twenty years from now, who knows?”

For now, Goes has more of a challenge with his family name.

“It comes up all the time, and I love it,” he said. “It’s certainly a name they won’t forget. I imagine a name like Goes would turn some people off, especially when we say it’s like ‘There he goes.’ But Goes means goose in Holland, and we’ve even had a goose around here.”

What Scherling loves, he said, is “working for people who are so progressive and want to not push it on families and persuade or convince or talk people into something like water cremation. But the fact that we can offer it and help families confidently understand and make those informed decisions about whether it’s flame cremation, water cremation, burial, green burial, anything and everything in between — at least we can offer our families everything we can, and that’s the perfect place to start.”

In the group Blood, Sweat & Tears’ 1968 hit song “And When I Die,” David Clayton Thomas sings, “All I ask of dying is to go naturally.”

The Grammy-winning Canadian vocalist is alive and well at 81. But if he would come to Northern Colorado or the Boulder Valley when his time is nigh, he might just get his wish — courtesy of businesses such as Goes Funeral Home in Fort Collins or The Natural Funeral in Lafayette.

Colorado for the better part of the past century has been a mecca of environmental consciousness and innovation, so it seems…