Brewers find climate changing

As a science fiction-themed brewpub that was launched in late February in east Longmont, Outworld Brewing’s mission is to boldly go where no taproom in the region has gone before.

As a science fiction-themed brewpub that was launched in late February in east Longmont, Outworld Brewing’s mission is to boldly go where no taproom in the region has gone before.

But will it live long and prosper?

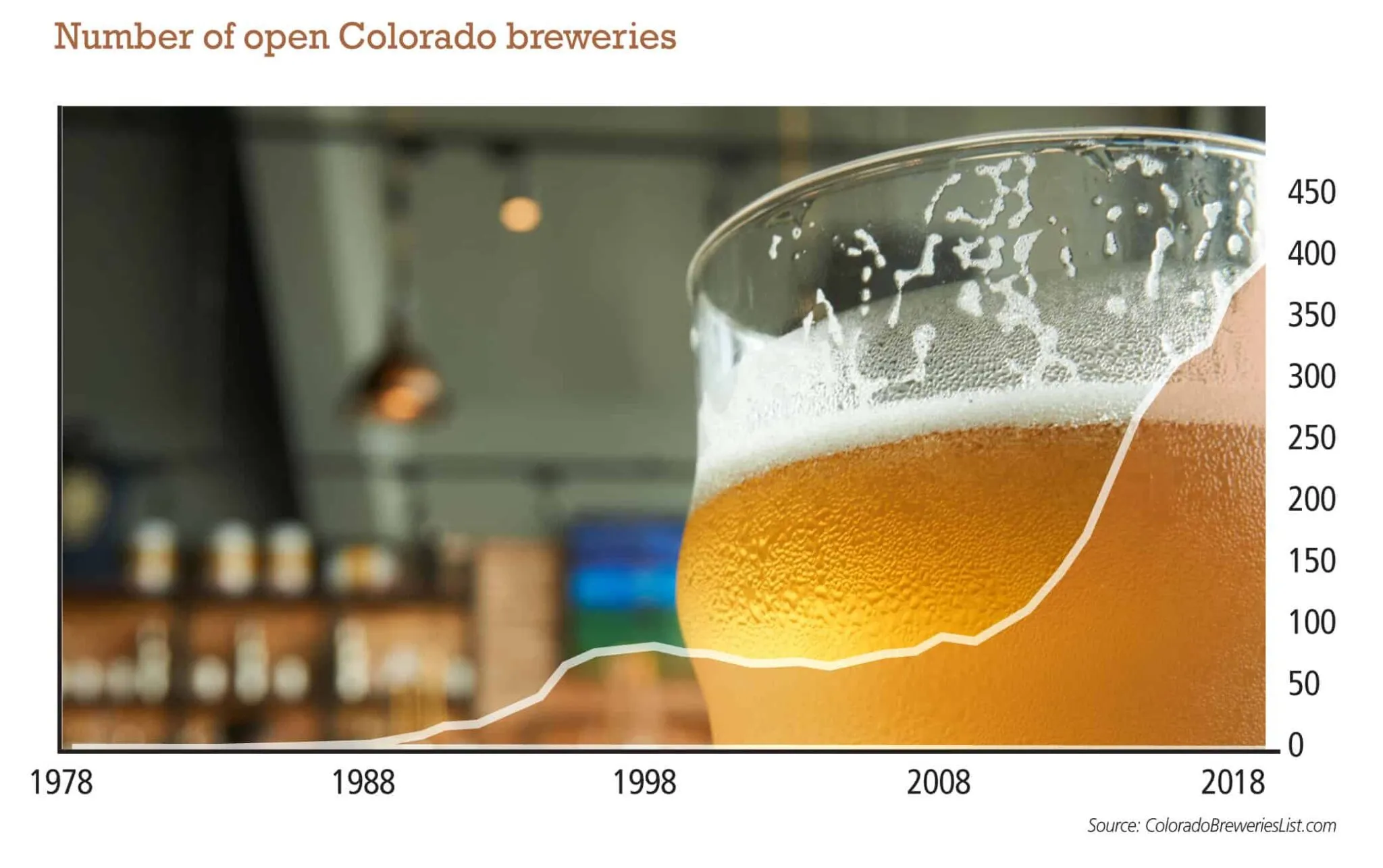

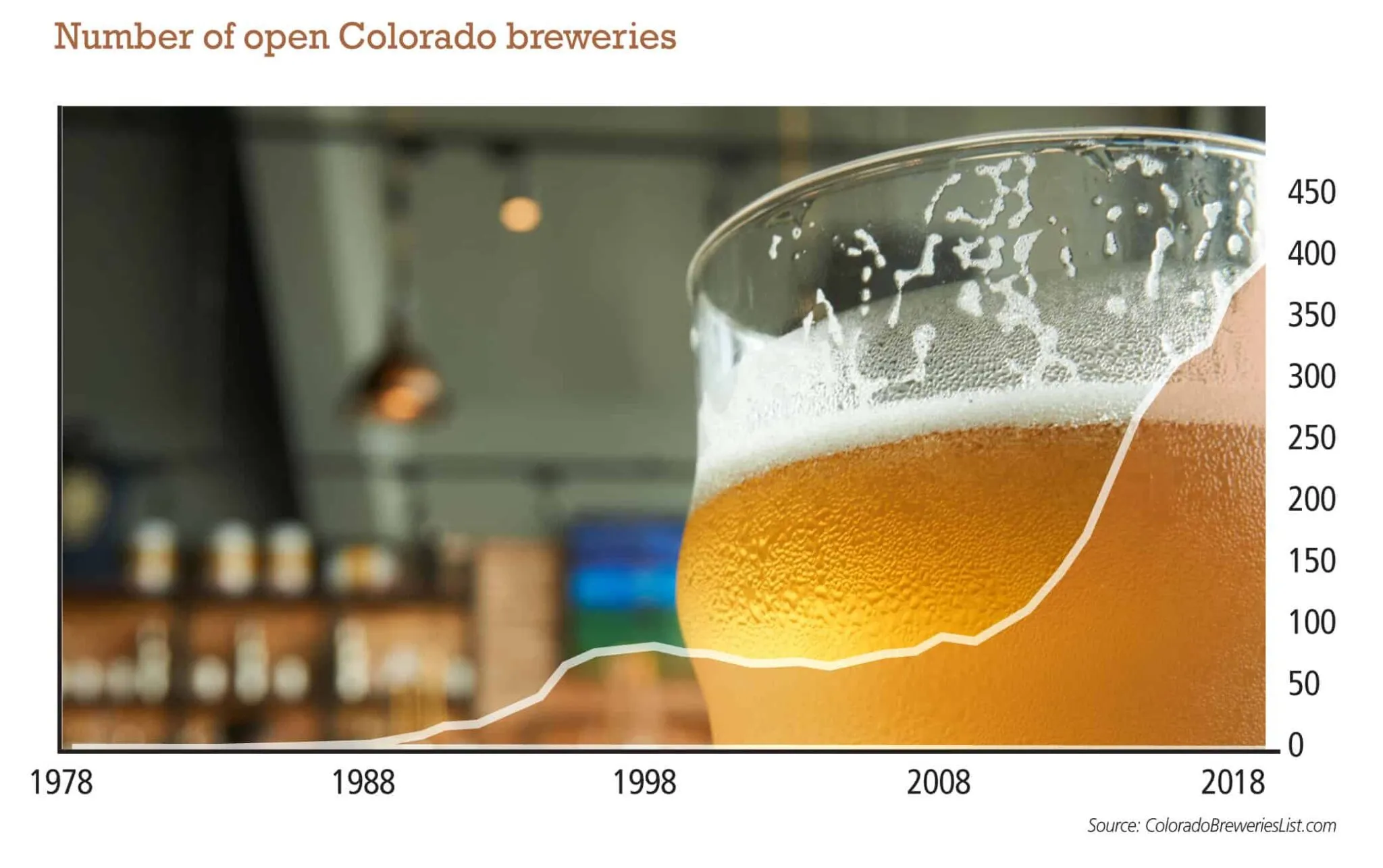

“Things have gotten a lot more competitive,” said Bart Watson, chief economist for the Boulder-based Brewers Association, “particularly on the Front Range, where we have one of the highest brewery densities in the country, if not the world.”

Outworld is steering into a maelstrom of competition in the Boulder Valley…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!