Liquor stores at a crossroads

A Longmont intersection is a symbolic battlefield in the war between Colorado’s independent alcoholic-beverage retailers and large grocery chains

Few shots are ever heard at the busy northwest Longmont intersection of Hover Street and 17th Avenue. And yet it’s a battlefield in a larger statewide war.

Independent liquor stores have operated for more than a decade near three of the junction’s four corners. But when the Safeway on the southeast corner began selling wine as well as full-strength beer thanks to new Colorado legislation, the trio of alcoholic-beverage retailers had to rethink their business strategies as well as their futures.

Economically as well as geographically, these neighborhood liquor stores are at a crossroads.

How we got here

Until the last decade, Colorado limited grocers to selling low-alcohol beer that contained no more than 3.2% alcohol by weight. That made shopping centers that included a supermarket a prime location for a nearby liquor store, and “mom-and-pop” alcoholic-beverage retailers thrived near almost every one of the state’s large chain grocery stores.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Retailers, including grocery stores, were limited under Colorado law to one license to sell full-strength alcohol. That meant that only one Colorado location for a chain grocer could sell full-strength beer, wine or spirits, with their other locations limited to offering 3.2% beer.

The Colorado Retail Council and the Colorado Consumer Choice Coalition, which organized a “Colorado Consumers for Choice” campaign, argued that Colorado should join 45 other states that allow grocery stores to sell full-strength alcohol.

In 2016, Gov. John Hickenlooper signed Senate Bill 16-197 into law, striking down a Prohibition-era law and allowing grocers, gas-station convenience stores and drugstores to sell full-strength beer beginning Jan. 1, 2019. Senate Bill 18-243 expanded the allowances two years later. The legislation was nominally popular in a state such as Colorado, with its large numbers of tourists and transplants who moved here from states where grocers could sell full-strength beer, wine and spirits.

According to the Colorado Department of Revenue, liquor licenses issued to grocers and convenience stores between 2017 and 2021 increased 17.3%. Although state data indicates the number of liquor stores operating in Colorado didn’t change much during that period, many independent liquor retailers saw SB 16-197 as the beginning of the end, paving the way for voters’ narrow approval of Proposition 125 in 2022 to allow wine to be sold by the food retailers as well, beginning March 1, 2023.

The major grocery chains supported Prop.125 and spent millions to get it passed.

“Customers have told us they want the convenience to be able to pick up a bottle of wine to have with a nice steak or a bottle of champagne for a special occasion,” Kris Staaf, a Safeway spokesperson, told The Denver Post. “We are really excited.”

Rick Reiter, campaign director for Wine in Grocery Stores, told the Colorado Sun, “Consumer habits are evolving, and it was inevitable that either this election, or one soon thereafter, that Colorado would become the 40th state to have wine in grocery stores.”

Other proponents pointed out that times change, and that liquor stores had been living in an entitled, legally-protective bubble too long.

‘We’re done, folks’

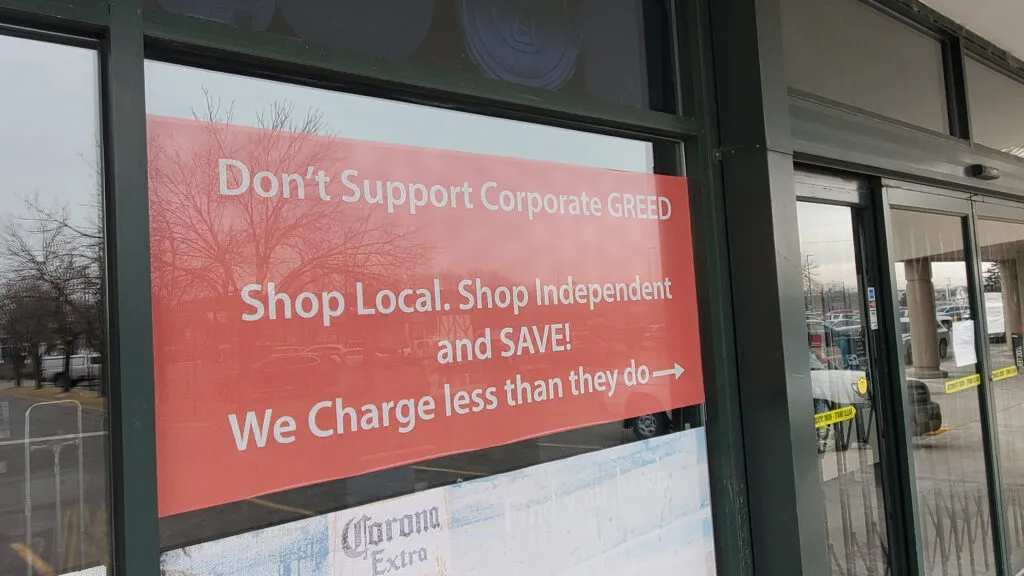

But one of the most outspoken independent liquor retailers to oppose Prop. 125 was Three Rivers Wine & Spirits, 1020 Ken Pratt Blvd. in Longmont, which posted a large, red sign in its window imploring customers not to “support corporate greed” and pointing out that “we charge less than they do,” with an arrow pointing at the Safeway just to the east.

It wasn’t enough. On Jan. 7, Three Rivers posted on its Facebook page that “corporate greed has won again. The lobbyists have paid our politicians, transplants have voted to make our state like their old ones, and Colorado now steps in line to destroy independent small business in favor of the grocery store chains and price club retailers.

“We’re done, folks. Going out of business. Everything has got to go.”

Eleven days later, it was over. The large retailer announced that it was permanently closed, then listed the names of the Colorado lawmakers who sponsored SB 16-197 and SB 18-243, “the initial bills to start destroying our industry. … They started the ball rolling by giving beer sales to all grocery stores and convenience stores, removing the 1,500-foot distance restrictions required for two locations to sell full-strength beer and wine, and giving the big corporations increased numbers of licenses for full retail liquor-store operations. … Welcome to the America where our politicians are completely for sale.”

Tom Wark, a wine-industry public-relations specialist, wrote in his “Fermentation” blog that “the voting public has sympathy for the little guy. That makes this kind of ‘David vs Goliath’ argument against wine in grocery stores slightly more effective. But you have to do some pretty serious demonization of the grocery stores that folks visit regularly and are dedicated to in order to sour those consumers on the very same places they visit multiple times a week and to which they have formed a bond.”

Still, the petition gatherers who stood outside Thompson Valley Liquor in Loveland to collect signatures to place Proposition 125 on the ballot were telling “flat-out lies,” said store manager Anthony Romero.

“They would paint it as something that would be good for the economy,” he said. “The fact is that it will create one job for every 12 lost.”

Added Mat Dinsmore, managing partner for two much larger liquor stores, Wilbur’s Total Beverage in Fort Collins and Wyatt’s Wet Goods in Longmont’s Village at the Peaks, “I guarantee King Soopers has not hired a single one of our people to offset the layoffs.”

Dinsmore said the Three Rivers owner’s online rant, and an even more earthy sign on that closed store’s door, “couldn’t have hit the nail on the head more directly.

“We told the story for a decade what these changes would do,” Dinsmore said. “If you want a case study of what buying an election looks like, this is it, $32 million.

“This is a quantum shift in how business has been done,” he said. “It worked for 100 years and everybody played by the same set of rules. That has now shifted.”

Thompson Valley Liquors, just a storefront away from a large King Soopers grocer, will close in mid-April, and many of the shelves in the 10,000-square-foot store already are half-empty. But Romero was still ringing up customers on a busy Saturday night.

He’s down to four employees now, when he usually had 10 to 12, Romero said, the result of an overall decline in sales he estimated to be around 30%.

“One thing that caught us by surprise was how much our beer sales took a hit” when King Soopers started selling wine, he said. He attributed the change to female shoppers.

“Women who would buy beer for their husbands would buy from us because they could also buy their wine here,” he said. “When wine went into the grocery store, they bought their beer and wine there while they shopped for food.”

Chris Fine, executive director of the Colorado Licensed Beverage Association, said his group estimates that one in every four — or maybe even one in every three — of Colorado’s approximately 1,600 independent liquor stores could close as a result of the legislation and ballot issue. That would mean 400 to 600 shuttered retailers.

Half of the stores his organization represents are owned by women, Fine said, and many owners are people of color who speak English as their second language.

At the crossroads

That’s the case on the southeast corner of 17th and Hover in Longmont, where Cambodian immigrant Sophanna Thann came to the United States in 2003 and opened Centennial Square Liquors in 2013, separated only by a Dollar Tree outlet from the 42-year-old Safeway store on the north end of the strip shopping center.

Thann estimated that his overall sales have been down 30% to 40% since the grocer next door put wine on its shelves.

“It’s been very bad business. I can see the slowdown a lot, especially wine and beer. Wine has been affected most,” he said, possibly experiencing the same effect Romero did in Loveland. “My wine is not making any profit right now. It’s a very small margin.”

As for beer, he said, “Modelo and Corona I’m still selling, but microbrews hardly at all. I’m still doing OK on spirits.”

Sales before last Thanksgiving were down 30% from the previous year, Thann said. “Christmas was down 20%, but I closed early, about 9 o’clock. New Year’s Eve, I was down 45% even though I stayed late. That’s terrible.”

How can his little store survive another year?

“I have no idea,” he said. “We try to work more hours, stay later. We find a way to lower the price, get customers into the store.”

Unlike Three Rivers and Thompson Valley, however, Thann said closing is not an option.

“I have no choice” but to stay open, Thann said. “My life is, I own this business to support my family.”

To the north, across 17th, general manager Rick Hines runs the far larger Hover Crossing Wine and Spirits at 1844 Hover St. The store has a customer loyalty program, holds periodic wine tastings, and occasionally invites independent producers of wines, ciders, spirits and craft brews in to give customers some branded swag and tastes of their products in hopes that they carry cans or bottles to the cashiers.

“We do tastings every Friday, some Saturdays, a few Thursdays as well,” Hines said. “We do tastings whenever the vendors are able. It broadens people. People get stuck with just one thing, but if we put liquid to people’s lips, it changes people’s minds. You might have an impression of what you think this might taste like, but until you actually have it … You may not want to commit to spending $20 on something, but if you get a free sample, you can see if you like it. It’s a good driver of us. It drives sales and gives us a little influence.”

And yet, Hines said, the store’s future might be as hazy as some of Oskar Blues’ India pale ales.

“Because the wine sales started [in grocery stores] in March, it hasn’t been a full calendar year yet, but just over that nine months of 2023, we’re single-digits down, pretty close to 9% down,” Hines said.

“The hits have been across the board just because total foot traffic is down, but even after all of that, wine is the biggest sector for loss,” Hines said. “And then this ‘dry January’ was a big deal; we had double-digit losses for January. It’s an Irish tradition; basically people take January off from drinking. It started around 2013 and finally made its way over here. We would see some effects of that throughout the years, but this year has been especially dry.

“Hopefully, February is a lot better than January,” Hines said. “If January is any indicator for this year, then no, we won’t survive. We might have six months left.

“Our store, we’re very blessed with our loyalty program and loyal customers and such, but it is definitely taken a percentage.”

To stay above water, Hines has been running Hover Crossing at “skeleton-crew” staff levels, but added that “I haven’t had to lay off. I have staffing issues as it is, and most of the people here — 14 or 15 — are part-time anyway.

“I’ve had a bunch of people quit and move on,” he said. “As those people are going away, it kind of worked out. We beef up staffing for the holiday season, but since January and February are so slow, it kind of helps to have people go away after that. Some of the people who have stayed, I’ve increased their hours.”

Purchasing has been affected as well, Hines said.

“We have not ordered some of our larger vendors’ distributors,” he said. “Some of our large bills, we’ve just not paid them and not ordered that particular week just to levelize the bill.”

Hines has little choice but to bank on hope.

“We definitely need an uptick in sales, for sure,” he said. “But we’ll see. People might party hard for the Super Bowl or get some Valentine’s gifts of booze. That would be nice as well. The next 90 days will be the true tell.”

Across Hover, on the intersection’s northwest side, and tucked into a strip center near a physical-therapy clinic, a bicycle shop and a soon to open “Thai 303” restaurant, Quick Liquors at 1751 Hover St. is the farthest of the three stores from Safeway, although it’s just south of a Rocket gas station and convenience store that also stocks beer and some wine.

It also seems to feel it’s farthest from the controversy, at least according to daytime manager Angelica Garcia. When asked which of her sectors had been affected most, her answer was quick and definitive:

“Nothing. Honestly nothing,” she said.

“We thought it was going to affect us, but it didn’t. It’s been steady,” Garcia said. “We’re the store that keeps things steady. We have a good relationship with our customers, so they like to come in here, whether it’s to buy something or chat with us. We have our loyal customers that just come in here every day. Nothing has affected us. They’d rather come in here and support us than going to the grocery store.

“Maintaining our relationship with our customers has helped a lot. Just having conversations with them and being friendly,” she said. “Of course, first impression is why they come back. All of our staff is very friendly, so that’s what we like, and we like to get our staff quick. We’re called Quick Liquors. We’re not called Slow Liquors. We’re called Quick Liquors for the reason that we can keep the line going. I don’t stop.

“I can’t say enough that the customer service is the big part in our store,” she said.

Garcia, who has been working at Quick Liquors for three years, said the store’s owner and staff knew the statewide measures allowing beer and then wine into food retailers was going to pass, “and we honestly tried to keep our prices maybe a dollar cheaper or at the same price as the grocery store,” she said, “but even if we have to make a dollar change higher than the grocery store, they still come here.”

Part of that first impression, she said, is keeping the store shelves looking full and healthy. Indicating the store’s north wall, which featured multicolored boxes of wine, Garcia pointed to an empty space that troubled her.

“I have this filled up at the beginning of the week, our boxed wine. And it’s now empty,” she said. “I’m going to have to order again on Tuesday. That’s already in the grocery store, but we continue to sell boxed wine. My boss doesn’t like to have any empty holes, because if we have empty holes, that means we aren’t selling, we’re not making money. So next week we’re going to have to refill all those empty holes.”

Vote ‘with your pocketbook’

Dinsmore is more worried about the “holes” left by closing stores.

Wholesalers he talks to have told him that “anywhere between 90 and 130 stores have closed across the state so far,” Dinsmore said.

“We had an economist do research right before COVID, when beer went into grocery stores in 2019,” he said. “We watched stores exit or people on the verge even then.

“COVID threw a lifeline to a lot of people. Our retail went up at the expense of our restaurant friends. It bought some people some time,” Dinsmore said. ‘But wine is a bigger part of the market, and a bigger revenue hit. I think 300 to 600 stores could close in a three-year period. Time will tell.”

Dinsmore said he gets phone calls from frantic store owners, pleading, “Hey, will you buy my remaining inventory?”

“There’s not a way to do that,” Dinsmore said, “but it is happening,”

Wilbur’s and Wyatt’s aren’t too big to feel the pinch as well.

“It’s hurt us, across the board,” he said. “Most of your stores can compete on service, selection and, give a buck or two, on price, but that convenience factor has hurt, and our customer counts have suffered. There’s even some big stores in Denver that may not be here this year.”

Some of those big stores were in favor of other issues on the 2022 ballot. Total Wine & More, which has three stores in metro Denver and nearly 250 across the country, was responsible for most of the money pumped into the campaign for Proposition 124, which would have let a liquor retailer run eight stores in a market immediately and an unlimited number by 2037. Colorado voters soundly rejected that one.

And Bart Watson, chief economist for the Boulder-based Brewers Association, pointed to what he saw as a silver lining in the two bills passed by the Legislature and the voter-approved Proposition 125.

“I think beer moving to grocery stores has been more positive for a lot of craft brewers,” Watson said. “We saw that with state tax figures. With more people shopping, they have more options.

“This wasn’t universally good or bad; that was based on the size of the craft brewers and their ability to access chain grocers,” Watson said. “Smaller brewers weren’t big enough, so as the foot traffic went down it was a little more negative. And in general, distribution is challenging for craft brewers right now. There’s a lot of brands.”

He sees the current climate as an opportunity for brewers to reassess how they get their product to market.

“It’s making brewers rethink how they distribute,” Watson said. “Maybe they’ll put more emphasis on their taprooms or their draft sales.”

Dinsmore wasn’t so sure.

“Craft brewers, they’re getting f***ed,” he said. “Unless you’re Odell or New Belgium, good luck.

“The local distilleries and wineries we all supported aren’t going to get the same support by a grocery store” that they get from us,’ Dinsmore said. “We supported them and even self-distributed all over Colorado — Fort Collins, Greeley, all the way to Lyons and Denver.”

Between Wilbur’s and Wyatt’s, Dinsmore said, “I am down at least 40 team members from a year ago, about 35%. This has impacted our revenue, and the only things you can cut are variable costs: head counts and inventory. Leases are fixed, and if you stop advertising, that’s the kiss of death.”

At his two stores, “wine took a bigger hit, a larger chunk of our business,” Dinsmore said. “In a lot of neighborhood stores, beer was the bigger hit. Either way, it’s death by a thousand cuts.”

He said right-sizing a business “is a lot easier to say it than do it.”

For liquor stores big and small, he said, a lot of the future depends on customers.

“We may have lost at the ballot box, but you can vote every day with your pocketbook,” he said. “You can support local, or you can support Cincinnati or Bentonville,” the corporate homes of King Soopers parent Kroger and Walmart, respectively.

“I get convenience, but where I buy, it matters when you think of these stores as part of your community,” Dinsmore said. “If they suck, don’t buy there. If I suck, don’t buy here.”

At his two stores, he said, the game plan is to focus on competing on price, paying attention to products’ “days on the floor,” giving better customer service and providing “a differentiating experience. We are going to provide a better experience.”

It’s a bittersweet time for Dinsmore.

“I love what I get to do,” he said. “I worked with my dad and opened Wilbur’s in 2000. He retired two years ago. I can’t say I’d want my kids to go into the business.”

A study by Colorado State University economics professors Nathan Palardy and Marco Costanigro that was released last March, just as Proposition 125 was taking effect, found that a pivot in strategy could be the best prescription for liquor stores.

While grocery stores certainly carry some craft brews, their shoppers are much more likely to be looking to grab a six-pack of Coors Light than a growler of their favorite hometown nanobrewery’s latest seasonal offering, Costanigro told BizWest last year.

The CSU study found that “liquor stores often carry a wide assortment of all alcohol types and provide knowledgeable staff that can help consumers make a selection. Consumers, therefore, may or may not change market channels depending on preferences and the purpose of the shopping trip.”

What’s next?

What will the future bring?

Dinsmore is pessimistic. Because of the throngs of newly arrived Coloradans who are used to all alcoholic products including hard liquor being sold in grocery, drug and convenience stores, he said, “there will definitely be a push at some point, legislatively or to a ballot,” to make that happen here.

“In Colorado, the number needed for a ballot measure is so easy to hit, the threshold is so low,” he said. It’s beer and wine today, he added, but what tomorrow? “Hard liquor? Pot? Mushrooms?”

Back at the crossroads of Hover and 17th, Hover Crossing’s Hines has no idea what tomorrow will bring for independent liquor stores.

“There are many people who have been in this industry a lot longer than I have who are scratching their heads,” he said. “I don’t think anybody can foretell what’s going to happen.”

Thompson Valley Liquors’ Romero has no such uncertainty, however.

“My short-term plan is to do construction with a buddy,” he said. “My long-term plan is to open up a bar.”

Independent sellers of beer, wine and spirits in the Boulder Valley and Northern Colorado are trying to cope with the impact of beer and wine sales at large grocery chains. Some of them aren’t making it.