Hewlett-Packard: A tale of three cities

Six decades after Hewlett-Packard Co. opened in Loveland, Northern Colorado campuses face different futures

Sixty years after Hewlett-Packard Co. employees first began moving into Building A on the company’s new Loveland campus in October 1962, the company that once grew to employ more than 9,000 workers in Loveland, Fort Collins and Greeley does not have the presence that it once did.

Today, HP’s successor companies — Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Co. (NYSE: HPE) and HP Inc. (NYSE: HPQ) — occupy 580,000 square feet in Fort Collins, with HPE employing 800 people. (HP Inc. did not respond to requests for information.)

But HP’s legacy extends far beyond that footprint, from spinoff companies that continue to employ thousands of workers to the real estate that HP left behind.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Much of the Fort Collins campus is now owned by Broadcom, which essentially is a spinoff of a spinoff, i.e. HP’s spinoff of Agilent Technologies Inc., which then sold its Semiconductor Products Group to an investment group, creating Avago Technologies Inc., which acquired Broadcom in 2015.

No HP employees remain at the Loveland site, where it all started, but another spinoff of a spinoff — Keysight Technologies Inc. (NYSE: KEYS), which grew out of Agilent in 2014 — maintains an operation there.

In Greeley, nothing remains of an HP operation that was once the center of the city’s nascent tech sector.

HP’s three Northern Colorado campuses have witnessed far different fates since the company began divesting local operations, and selling local properties, with tech remaining the driving force in Fort Collins, and tech and manufacturing enjoying a resurgence at what was the Loveland campus. Greeley, however, has seen demolition of the long-vacant HP building, with the bulk of the acreage transformed for residential, retail and other uses.

Loveland

Hewlett-Packard Co.’s history in Northern Colorado began in Loveland, but it almost didn’t start that way. Loveland had to compete with Boulder for an HP expansion, but problems with potential Boulder sites — and a strong pitch from Loveland civic and business leaders — prompted Colorado native David Packard and other HP executives to select Loveland instead, according to an HP Computer Museum post on the history of the Loveland plant.

The plant — with a temporary building opening in 1960 and the first permanent building in 1962 — initially produced power supplies but eventually began producing desktop computers and calculators. HP’s Loveland operation also produced a variety of computer peripherals, including printers and instruments, such as voltmeters.

The campus — on the northeast corner of South Taft Avenue and 14th Street Southwest — remained a bastion for HP’s global operations for decades, but change began in the late 1990s.

HP spun off Agilent in 1998, and by 2005 only 500 people remained at the Loveland site, according to the HP Computer Museum.

The Thompson School District acquired one building on the former HP/Agilent campus in 2004, an 88,000-square-foot building at 800 S. Taft Ave. that was formerly home to Colorado Memory Systems Inc., which built the structure in 1984. Colorado Memory Systems was founded by former HP employee Bill Bierwaltes. The company manufactured computer tape backup systems and was acquired by HP in 1992.

The school district purchased the building for $4.7 million and now uses it for its headquarters.

Just to the east is Keysight Technologies, at 900 S. Taft Ave. Keysight spun off from Agilent in 2014, developing test and measurement equipment.

Keysight’s Loveland building encompasses more than 139,000 square feet.

Kari Fauber, vice president of Keysight’s global partner sales and ecommerce, told BizWest in an email that the Loveland facility is “primarily a research and development site, but also hosts teams from legal, sales, marketing, finance, logistics and services.

“Keysight delivers advanced design and validation solutions that help accelerate innovation to connect and secure the world,” she said. “Keysight’s dedication to speed and precision extends to software-driven insights and analytics that bring tomorrow’s technology products to market faster across the development lifecycle, in design simulation, prototype validation, automated software testing, manufacturing analysis, and network performance optimization and visibility in enterprise, service provider and cloud environments.”

Keysight’s customers span the worldwide communications and industrial ecosystems, aerospace and defense, automotive, energy, semiconductor and general electronics markets, Fauber said.

Keysight also maintains operations in Colorado Springs and Boulder. It acquired Eggplant Software Inc., with U.S. headquarters in Boulder, in 2020 for $330 million.

Keysight employs 14,300 worldwide and employed about 300 people in Loveland at the time of the spinoff from Agilent. The company recorded revenue of $4.94 billion in 2021.

With Agilent’s retrenchment in Loveland, the company negotiated a deal in May 2011 to sell the bulk of the Loveland campus to the city for $5.8 million.

Plans to revitalize the campus were ambitious, with the Colorado Association of Manufacturing and Technology eventually selecting the site in June 2011 for an Aerospace and Clean Energy Manufacturing and Innovation Park, known as ACE. The project was touted as creating up to 10,000 jobs.

But the proposal faltered early on, with developer United Properties withdrawing from the project in August 2011, citing unattainable timelines.

Loveland then selected Bowling Green, Kentucky-based developer Cumberland and Western to develop the property, with the city selling the property to the company for $5 million.

Plans for the ACE park formally ended in March, when CAMT withdrew from the project.

Even before that, Cumberland and Western had rebranded the site as the Rocky Mountain Center for Innovation and Technology.

Cumberland and Western invested in upgrades to the property, including some tenant finishes, and successfully lured Lightning eMotors Inc. (NYSE: ZEV) as a tenant. In April 2016, Cumberland and Western announced that EWI, a Columbus, Ohio-based organization that promotes manufacturing technologies, would open an applied research center at RMCIT.

But it all wasn’t enough, and Cumberland and Western opted through commercial brokerage CBRE to put the property on the market for $22.8 million in October 2020.

Loveland site sells, rebrands

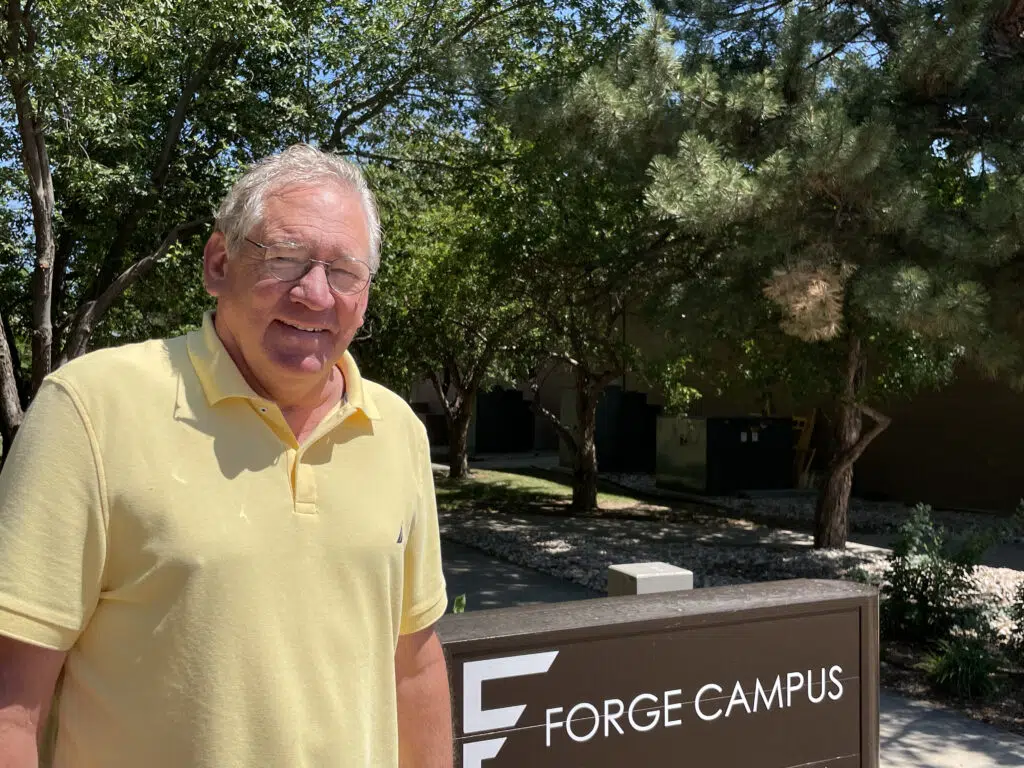

Cumberland and Western eventually found its buyer, although not for the full asking price. In late October 2020, a group of local business owners, led by Jay Dokter, Josh Kamrath and Dan Kamrath, purchased the 811,000-square-foot property for $15.5 million under the entity RMCIT LLC.

Dokter, CEO of Loveland-based Vergent Products Inc., and his partners began working to increase occupancy from an anemic 16%.

The new owners quickly got to work, rebranding the property as the Forge Campus in March 2021.

“We just observed all of the potential that didn’t happen and thought, ‘We could do that,’” Dokter said. “What we saw was 40 to 50 companies in here, collocated, creating an innovative tech environment. And the price was right, too. So we knew that it wasn’t as risky. We also saw building prices were going up for a lot of commercial.”

Cumberland and Western’s initial approach to the property was to secure a single, large occupant, Dokter said.

“I think there was a fair amount of activity. They seemed to be going more for the grand slam, one occupant, and that market is extremely limited,” he said, adding that Cumberland did refocus to allow smaller companies in.

The vision of Dokter and his partners was clear from the beginning: Create an environment in which occupants would build an innovation ecosystem, interacting and feeding off of one another.

The owners moved one of their own companies into the Forge — Bongo, which provides video-assessment solutions for experiential learning. The investors also plan to relocate another of their companies, Vergent Products, a contract design and manufacturing company, into the facility within a couple of years.

Dokter said one of the key advantages of the Loveland property was the maintenance that Cumberland and Western provided for almost a decade.

Often, vacant properties are allowed to decay, with damage by weather, vandalism and neglect. Not so with the Loveland site. Cumberland and Western continued to employ a team of one part-time worker and three full-time workers to maintain the property and conduct real estate tours.

“The cool thing with Cumberland and Western is that they spent a lot of money maintaining the property,” Dokter said. “I never forget, the first time I came here to get a tour … there was a nice man waxing the floor over here in an empty building — one of those machines that go back and forth in an empty building. That impressed me that it was quite preserved.”

“Big buildings like this, you don’t just shut the lights off and walk away,” said Rob Blauvelt, property manager for the Forge and one of the full-time workers who maintained the property during the Cumberland and Western years.

Cumberland and Western maintained a contract for upkeep of the 22 acres of roof. Landscaping was maintained, although at a lower level than when the property was occupied. Cracks in parking lots were filled. HVAC systems were maintained.

“It was three and a half people watching an empty building for 11 years,” Dokter said.

The property’s 16% occupancy at the time of purchase included 12 tenants, but that number has doubled to 24. Another five tenants are housed on-site in The Warehouse accelerator, a nonprofit organization that occupies 48,000 square feet of donated space.

Allison Seabeck, executive director of The Warehouse, said the organization has three alumni members and three off-site members, along with the five onsite members.

A capital campaign has raised $1.1 million out of a $4.8 million capital raise, allowing the organization to add a staff member and proceed through Phase I of its construction plan, creating space for nine companies.

Phase II of the capital campaign entails raising another $1.25 millon, including $750,000 to create space for 15 more companies, including installation of a series of “garage pods” in the accelerator space, providing turnkey manufacturing space for startups that need access to manufacturing floor space, equipment, ample power, compressed air and other features.

Future expansions will include further buildout, including community space, a training room, additional equipment, a share marketing studio and other amenities.

Including The Warehouse, occupancy at the Forge stands at 54%, Dokter said, with other leases pending.

One recent addition is Veloce Energy Inc., a Los Angeles-based company that produces modular devices to make electrification easier.

Veloce moved its Colorado location from north Fort Collins into the Forge campus in May. The company employs 12 people locally.

Additionally, E.I. Medical Imaging, a trade name for OrcaWest Holdings Inc., will move into the Forge. E.I. Medical Imaging develops real-time ultrasound devices for use by veterinarians and livestock producers.

Lightning eMotors, which Cumberland and Western first brought to the site, has expanded rapidly, growing from 142,386 square feet when Dokter and his team acquired the property to 250,000 square feet and 260 employees. The company provides commercial electric vehicles for fleets and went public in 2021.

The Forge thus far has a mix of large clean-tech and other manufacturing companies.

“They’re more complimentary than you would think,” Dokter said of the tenant mix. “That is the whole idea. We want to do more and more mixing and explaining who does what.”

With Vergent Products, Dokter already has two clients within the Forge, with another three potential clients. That cross-pollination can be seen among other tenants as well, he said.

One additional amenity will foster even more interaction: The Forge soon will reopen the old HP cafeteria, bringing a variety of local restaurant and catering companies in to provide a mix of dining options.

Blauvelt stressed the quality of the construction that is attractive for potential manufacturers.

“What you have here are structurally sound buildings with solid floors, with a massive amount of power, a massive amount of heating and cooling water, a good amount of compressed air, infrastructure for process vacuum … and you have a campus that’s just inviting as a workplace,” Blauvelt said.

“This thing has awesome bones,” he added, “and it’s really easy to fit a business into here. It’s not very challenging to fit a complex operation into this space.”

And that 22 acres of roofs? Future plans call for installation of solar panels, further emphasizing the site’s focus on clean technologies.

Stability characterizes Fort Collins site

No city in Northern Colorado has maintained as much of HP’s legacy operations as has Fort Collins, a site that opened in 1978 and employed as many as 3,200 HP workers at its peak.

In fact, HP — both Hewlett Packard Enterprise and HP Inc. — remain prominent employers on the campus, located on the northeast corner of East Harmony and Ziegler roads — with HP Inc. leasing space within Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s two buildings on 71.5 acres.

Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s operations there employ 800 workers and are varied.

“The Fort Collins site houses a range of business units and functions — from servers to R&D to marketing. It’s a multi-use facility and not dedicated to any specific part of the company,” Adam Bauer, a spokesman for HPE, said in an email to BizWest.

The Fort Collins campus sits on the East Harmony Road corridor, the focal point of a cluster of high-tech companies that includes Broadcom, Intel Corp., Advanced Micro Devices and others. “Certainly, having other tech players with whom we partner and do business in close proximity helps create an ecosystem that is mutually beneficial,” he said. “That’s true in Fort Collins, Silicon Valley, Houston — everywhere we have a large presence.”

Bauer said that Fort Collins “is an important location for HPE, and again, is host to a range of business units and functions that span the company. It remains one of our biggest employment hubs in the U.S. and is an important part of our history. We do not anticipate any change to Fort Collins’ role in the company at this time. We actually are in the process of renovating the site to accommodate our hybrid, Edge-to-Office working model that arose out of the pandemic.”

HPE leases space to HP Inc., which did not respond to BizWest requests for comment. The city of Fort Collins estimates that HP Inc. employs 1,100 local workers, but that number could not be verified.

HPE in April 2019 sold a building on the Fort Collins campus — at 3420 E. Harmony Road — to an entity owned by McWhinney Real Estate Services Inc. of Loveland for $21 million. Bauer declined to speculate on any plans to sell additional properties.

“We continuously evaluate our real estate portfolio based on a variety of criteria including usage, opportunities for cost optimization, and other factors,” he said. “I can’t speculate on future real estate transactions.”

The McWhinney building is largely vacant, although fully leased. Madwire formerly occupied the third floor and a first-floor gym space, but the company has put the space on the sublease market, although it continues to pay rent.

Additionally, Comcast Corp. (Nasdaq: CMCSA) has vacated 80,000 square feet within the building. The company had opened a call center in 2016, with plans to house up to 600 employees.

But those plans changed in September 2019, when the company announced closure of the operation. Comcast’s lease expires in 2027, with the space put up for sublease.

A federal contractor based in Maryland, ASRC, or Arctic Slope Regional Corp., leased 31,000 square feet of the Comcast space in August 2020. The company operates as a contractor to federal intelligence, aerospace and health-care information-technology agencies.

Micro Focus, a spinoff of Hewlett Packard Enterprise, occupies about 16,000 square feet in the building.

Peter Kast, a broker with CBRE who is listing space in the building for sublease, said the campus and other corners of East Harmony and Ziegler roads benefit from infrastructure put in place to serve HP.

“If you look at it from an infrastructure point of view, it’s one of the few places in town that has redundant fiber and redundant fiber, so people like this that have needs for those kinds of things, there’s not that many choices, so in terms of an infrastructure location, it’s great,” he said.

He noted that HPE, HP, Broadcom, Intel, AMD and other high-tech companies in the area capitalize on a concentration of skilled workers.

“The thing that’s so attractive about Fort Collins for these guys is the intellectual capital, the people who do this kind of work, who are trained to handle, whether it’s software or hardware design,” he said. “We’ve got a ton of people who do chip design in this town.”

The biggest player in that space locally is Broadcom, which has continued to invest in its Fort Collins operation. Although the city of Fort Collins estimates that Broadcom employs 1,150 workers locally, the company told BizWest in 2019 that it employed 1,747, including 1,313 employees and 434 contingent workers.

Broadcom owns a large swathe of the former HP campus, with its predecessor, Avago, completing several major expansions.

The company, in its most-recent quarterly report filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, cited ongoing supply-chain disruptions brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and highlighted the importance of the Fort Collins operation.

“We have been, and expect to continue, experiencing some disruption to parts of our global semiconductor supply chain, including procuring necessary components and inputs, such as wafers and substrates, in a timely fashion, with suppliers increasing lead times or placing products on allocation and raising prices,” the company reported, noting shutdowns at key suppliers and service providers around the world.

“Any similar disruption at our Fort Collins, Colorado manufacturing facility would severely impact our ability to manufacture our film bulk acoustic resonator (“FBAR”) products and adversely affect our wireless business,” the company said.

Despite those challenges, Broadcom, HP and related companies remain key components of the Fort Collins economy.

SeonAh Kendall, senior economic manager for the city of Fort Collins, said Hewlett Packard, Broadcom and other companies in the East Harmony Road corridor are “going strong.”

“We are seeing that they’re kind of staying in the area and growing with spinoffs in there as well,” she said. “I do think that it is a critical piece for us in terms of the employment as well as the contributions that the companies as well as employees have in our community.

“There are opportunities for additional growth in those locations,” she added, “and opportunities for a lot of collaboration. I think one of the greatest strengths is that we’re able to retain the talent here. Sometimes, we have seen folks leave AMD and go to Intel, or leave Intel and go to HP and vice versa.”

She noted that companies in the area work closely with Colorado State University, Front Range Community College and the Poudre School District on issues such as talent and retention.

Greeley facility sees different fate

Greeley’s Hewlett-Packard facility was the last to be built, the first to close and the only one to be torn down — at least most of it.

The facility, opened in 1984, focused on scanners, tape drives and other devices, but HP closed the operation in 2003, shifting what was then 800 workers to other locations. About 640 workers were transferred to Fort Collins, with another 165 shifting to Flextronics International Ltd. Flextronics purchased DII Group Inc., which was buying HP’s tape-storage manufacturing business.

HP put the property on the market and seemed to attract widespread interest at first, including for a potential expansion of Aims Community College. But that and other deals fell through, prompting HP to sell the building to a group of local investors. HP sold the 355,000-square-foot property on 157 acres in August 2004 to Boomerang Properties LLC, headed by local investors Bruce Deifik and Jeff Bedingfield, a Greeley attorney. The purchase price was $8 million, far lower than HP’s $14 million asking price.

“Up to this point, HP has not been willing to divide the property or divide the facility,” Bedingfield told the Northern Colorado Business Report, a predecessor to BizWest, in August 2004. “Their desire is to sell everything and let the buyer determine how best to use it.”

Boomerang intended to subdivide the HP building to support perhaps four smaller tenants.

“There’s been a lot of talk that you can’t get big blocks leased, that the best thing is to bulldoze the facility,” Bedingfield said in 2004. “It’s too fine of a facility to begin talking about any kind of changes to that place, other than demising it into large blocks.”

But the new owners also envisioned that surrounding acreage would be transformed into residential neighborhoods, retail centers and office uses.

The project soon was taken over by City Center West LP, a Denver development company affiliated with Westside Investment Partners Inc., which acquired the building and adjacent acreage for $8.36 million in 2007. Some holdings were owned and developed under the umbrella of BV Retail Land Holdings LLP.

City Center West began selling acreage for retail, residential and other uses:

- In 2011, the company sold 12 acres to a North Colorado Medical Center/Banner Health entity for $2.34 million. Banner continues to own the vacant land.

- In 2014, City Center West launched a commercial development on the northeast corner of 71st Avenue and West 10th Street, eventually adding a Bank of Colorado branch, McDonald’s, Breeze Thru Car Wash and a Les Schwab tire center.

- Developers of a self-storage facility purchased land along 71st Avenue. That property now houses Boomerang Self Storage.

- A memory-care facility, Windsong at Northridge, was built along 71st Avenue.

- A chunk of the HP building — the cafeteria and events center — was redeveloped into the West Ridge Academy at 6905 Eighth St.

City Center West continues to own residential land on the former HP campus but sold the remaining vacant building and some acreage to LaSalle Investors LLC, a unit of Waltel Cos. Inc. LaSalle demolished the remaining HP building, preparing the site for future development.

But the company faces opposition to plans to rezone the property from Industrial – Low Intensity to Residential – High Density. About 10 neighboring residents voiced opposition to the rezoning request at a June 7 Greeley City Council meeting.

Residents voiced fears that LaSalle planned to build a large apartment complex on the property, which they said could exacerbate existing traffic problems.

Several City Council members also voiced opposition to the R-H zoning, preferring a less-intensive Residential – Medium Density zoning.

“It’s just too intense right now,” Councilman Dale Hall said. “I’m uncomfortable making this R-H. I’m OK with Residential Medium Intensity.”

In the end, LaSalle’s attorney asked that the council continue the discussion to the July 19 City Council meeting.

Greeley’s westward expansion

Why Greeley’s HP facility faced such a different outcome than campuses in Fort Collins and Loveland can be attributed to a variety of factors.

First, the technology sector in Greeley has never developed to the scale of Fort Collins’ or Loveland, which enjoy closer proximity to Colorado State University. Even before HP’s closure, Greeley had seen the departure of home-grown printed-circuit-board manufacturer EFTC Corp., founded in Greeley as Electronic Fab Technology Corp., which left for the north Denver suburbs.

But the greatest factor seems to be the pattern of Greeley’s residential and commercial growth, which has pushed inexorably westward for several decades.

Benjamin Snow, director of economic health and housing for the city of Greeley, said the area around “the core of the apple,” meaning the HP building, has transformed.

HP’s Greeley facility was once on the city’s outskirts, with little nearby retail and far less residential development.

“When you look at what’s happened over the last 10 years out there, it has sort of defaulted to what I would describe as typical suburban growth,” Snow said, pointing to the King Soopers and other retail development across 10th Street, as well as retail and residential projects on former HP land surrounding the building.

He noted that for years, he and his predecessors in the economic-development community sought to preserve the industrial zoning for the building as a way to balance the city’s housing stock with a solid employment center.

“It just never took,” he said. “We never could get a secondary use in there … At some point, you have to listen to the market signals.”

Although many potential users toured the facility, one obstacle, he said, was that the building had fallen into disrepair.

“Once people went in, because that building essentially had been neglected and abandoned for so long … it was kind of a magnet for that kind of vandalism. There was evidence that people were inside the building at different times.”

“Greeley has tried for 20 years to get some industrial users to reinhabit, to reanimate that building, to no avail,” he said.

Additional reading: “HP in Colorado,” Measure (HP’s inhouse publication), November-December, 1982.

Sixty years after Hewlett-Packard Co. employees first began moving into Building A on the company’s new Loveland campus in October 1962, the company that once grew to employ more than 9,000 workers in Loveland, Fort Collins and Greeley does not have the presence that it once did.

Today, HP’s successor companies — Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Co. (NYSE: HPE) and HP Inc. (NYSE: HPQ) — occupy 580,000 square feet in Fort Collins, with HPE employing 800 people. (HP Inc. did not respond to requests for information.)

But HP’s legacy extends far beyond that footprint, from spinoff companies that continue to employ thousands of workers…