‘It takes a village’

Collaborations called key to providing affordable housing

LOVELAND — Whether it’s rewriting land-use codes to increase density, passing tax increases, forming metro districts or relying on philanthropy, addressing the region’s growing need for affordable or attainable housing has proved ever more vexing.

But as government officials, developers, nonprofit directors and students who attended BizWest’s Northern Colorado Affordable Housing Summit on Thursday at Loveland Yards agreed, not much can be accomplished unless all sides communicate, cooperate and innovate.

Or as Doug Dohn, owner of Fort Collins-based Dohn Construction Inc., put it, “It takes a village.”

SPONSORED CONTENT

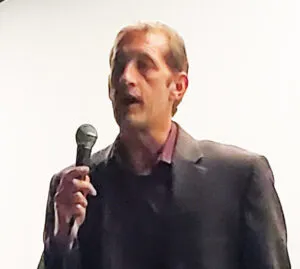

Before the diverse group of stakeholders at the summit separated into brainstorming conversations to bat ideas around, they heard keynote speaker and moderator Pete Thrasher, director of the Everitt Real Estate Center at Colorado State University’s College of Business in Fort Collins, plead, “Don’t let this die in this room.

“The whole point of this,” Thrasher said, “is, can we figure out how to solve this issue. If this was easy, it already would have been solved.”

Thrasher brought Northern Colorado’s affordable-housing crisis home with a series of startling statistics that told the story.

“Most people think about affordable housing as subsidized housing,” he said, but “the true definition of affordable housing is not using more than 30% of your gross income for housing costs plus utilities.”

According to standards set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Larimer County’s area median income is $118,000, while Weld County’s is $114,500, Thrasher said.

“At 30% of AMI, you’re going to see those folks in homeless shelters, transitional housing or permanent supportive housing,” he said. “Affordable” rental housing targets people making between 30% and 50% of an area’s AMI, he said, and first-time home ownership is at 50% and above. “From 60% to 100% AMI, that’s your middle income.”

But can those families afford housing in Northern Colorado?

A family of four at 80% of AMI — that’s a household income of $7,921 per month or $95,050 a year — could barely cover housing costs plus utilities, he said.

“That family can actually afford a home priced at $376,000 in Fort Collins,” Thrasher said, “and there’s very few homes for sale in Fort Collins right now for $376,000 or less.”

The situation is more dire if a homeowner’s association is involved, he said. “The average HOA fee is $250 a month, so now we’re talking about that family can only afford a home for $333,000 — and Fort Collins only has 55 homes available below that price.”

Considering that the statewide average cost to build a house is $434,000, a middle-income family can only afford one for $334,000, and middle-income families make up “44% of our whole marketplace,” Thrasher said, “that’s our ‘missing middle’ And what do you do in these rural areas when the cost of the buildings themselves on resale are less than what it costs to build the product?”

He said one-third of residents in Loveland are “housing burdened,” meaning they use more than 30% of their income for housing and expenses.

“In order to afford a median home in Larimer and Weld, as a household you need to make 196% of household AMI,” Thrasher said. “You’d have to have two earners in your household at middle income to get up to a household income of 196% AMI.”

How do those families cope?

“There’s this whole thing called ‘drive until you qualify.’ That definitely happens,” Thrasher said. “People are saying, ‘I can’t afford Larimer County, I’m going to Weld County. No? That’s OK. I’m going to keep going east. I hear Kansas is cheaper.’”

The problem in driving home the impact of the housing crisis to a voting and taxpaying citizenry, he said, is that they’ll say, “I own a home. Why should I care about affordable housing?”

One reason Thrasher gave involves students from housing-burdened families who can barely afford adequate school clothing, much less other school supplies and sports equipment.”

“Think about what that cycle does for that one kid,” Thrasher said. “If you can give some of those kids and these families this housing stability, it can kind of circumvent the cycle a little bit.

“It builds stronger individuals, it builds stronger families, it builds stronger communities. And that’s why.”

The availability of land and water, utility access, the time it takes to bring a property to market and a plethora of government regulations aren’t the only obstacles to affordability, Thrasher said. Nodding to many of his CSU students in the room who will aspire to be first-time homebuyers, he said, “If people age in place, it doesn’t leave vacancies for the people coming in.”

The situation isn’t all doom and gloom, however, Thrasher said.

“There are a lot of solutions already out there people have been trying, and we need to continue to innovate and think about more and more solutions,” he said, stressing that coming up with them was the whole point of Thursday’s workshop exercises, which brought government officials, nonprofit representatives, developers and students together at each of a score of round tables.

Ideas generated at the tables included forming regional advisory boards to coordinate efforts between cities, streamlining the approval process, and addressing legislation such as the Construction Defect Action Reform Act that has especially hindered the construction of condominiums. Adopted in 2001, the act was intended to regulate claims when a purchaser is claiming construction defects. Though later amended, the law has restrained construction of condos.

Thrasher said fee reductions, tax abatements and fast-tracking approval processes could be part of the answer, along with increased funding opportunities through the state’s Proposition 123. Passed by Colorado voters in 2022, the measure made several hundred million dollars in affordable-housing funding available. The state Department of Local Affairs and Office of Economic Development and International Trade oversee the money, which is provided through grants and loans to nonprofit agencies, community land trusts, private entities and local governments. That’s “one important fix,” Thrasher said.

However, panelist Kristin Fritz, chief real estate officer for Housing Catalyst in Fort Collins, wasn’t quite as enthusiastic.

“Every time a new exciting funding source becomes available, another one goes away,” she said. “It’s just another justification that we don’t need to use that resource any more because now we have this new gap funding.”

But all — on the panel of executives as well as at the tables — agreed with Deb Callies, the City of Greeley’s director of housing, that “partnerships are the key.”

Callies emphasized “how important attitude is in these partnerships,” especially “the attitude between government and private developers. If you can get past some of this kind of us-versus-them kind of relationship that has happened, then we can come to the table and really problem-solve together.”

From an economic-development standpoint, added Nicole Staudinger, president of FirstBank in Northern Colorado, “we really need to figure out how we’re supporting these builders and developers in bringing products that are affordable to shore up the missing middle.”

One of those developers, Landon Hoover, president and owner of Hartford Homes, agreed, calling out what he called the attitude of some city officials that “you have to protect the public against developers. I think we have to break that line of thinking and say how do we collaborate.

“I’m not saying get rid of any protections,” Hoover said, but added that overregulation is “going to make the problem worse, not better.

“City officials are giving us way too much credit,” he said. “We are not very sophisticated. What we do is, we add up the costs, then we put a margin on top, then that’s what we sell. If we can sell more at that, we sell more at that. If we can provide housing at a more affordable rate and hit our margins and sell more of it, we’ll do that all day long.”

Hoover challenged everyone in the room to examine their goals.

“Cities need to really define their priorities, and you have to live by those priorities,” he said. “Many of our communities say affordable housing is a top priority, yet they implement energy codes that increase the cost of housing by 8, 10, 11 grand overnight.

“It’s OK if we want energy efficiency or if we want a level of service above other communities, but we can’t say affordable housing is our priority then,” Hoover said. “If we’re implementing energy codes, then we need to say energy efficiency is our priority over affordable housing. That may be a fine prioritization, but our community has to be genuine in that. If we say affordable housing is our priority, then we’ll make the hard tradeoffs. We’ll take the leadership that it takes to not do something that’s good.

“If you try to do everything that’s good,” he said, “you’re going to end up with none of it.”

Hoover also argued that subsidies are not the way to solve the affordable-housing crisis. “They may be part of the solution, but we cannot subsidize our way out,” he said.

He pointed to Fort Collins’ strategic housing goal of having 10% affordable housing in the city by 2040. “Right now there’s only 5% of the existing housing stock,” he said. “By 2040, they want to make up that 5% and have 10% new. That’s 6,500 units out of 25,080 by 2040; 26% of the new housing stock has to be affordable.

“What level of subsidy would it take to take the market rate cost down to affordable? A $150,000 subsidy,” he said. “And with $150,000 times 6,500, we have a billion-dollar challenge in Fort Collins alone.”

Hoover pointed to some bright spots in Fort Collins, including the collaboration between Hartford, Habitat for Humanity and the Odell family of brewing fame, which donated the land for the Tapestry project.

“This partnership took about two years to form,” Hoover said, “and it took some radical generosity on the part of the Odell family.”

In answer to Larimer County Commission chairman John Kefalas’ question about what incentives could be useful for developers to build smaller-sized homes, Hoover pointed to the Bloom development, where Hartford is building 900- to 1,500-square-foot cottages on 26-by-90-foot lots. “Bloom’s a great example of Fort Collins using metro districts as incentives,” he said.

Once approved by city councils, metropolitan districts permit developers to set up mini-governments that have taxing and bonding authority. Metro districts have flexibility to use bond and tax money for a wide range of infrastructure and amenities. Eventually, the boards that control metro districts are made up of property owners in the district, but initially the developer controls the boards and typically will obligate the district using the bonding authority permitted by law.

Still, “this problem can’t be solved just through tax credits, through grants, through subsidies, through philanthropy,” Hoover said. “It’s going to take a lot more bold strategies in order to do it. I would argue that it’s not a subsidy challenge. I think this is a cost challenge.”

Fritz agreed, citing increases in the costs of materials, fee hikes, higher interest rates and higher land prices. “That gap has only gotten bigger,” she said. “If we want to prioritize affordable housing, there are a lot of partners that are going to have to be involved.”

The hard questions, she said, are, “how do we maximize the resources that are available? How do we be strategic about the limited resources so that we’re not just in competition for these limited resources that are available? There’s not enough to go around.”

Costs were reduced in Fort Collins, Hoover said, when “we had building codes changed, we had land use codes changed, we had energy codes updated.”

Eric Hull, director of real estate development for the Loveland Housing Authority, cited the work of an affordable-housing task force in that city that crafted “really exciting amendments to the city’s unified development code that supports and fosters more affordable and attainable housing.”

“The good news is that construction costs are starting to stabilize,” Dohn said. “The bad news is that the supply is going down as demand is going up.”

Cheri Witt-Brown, CEO of Greeley-Weld Habitat for Humanity, solved at least one piece of the supply problem by getting Habitat into the developing game and created one of the West’s largest affordable-housing projects.. Habitat’s Hope Springs development in Greeley is bringing more than 300 affordable apartments, a park and a child-care center within walking distance to schools, grocery stores and mass transit. The development also includes 174 single-family housing lots from Habitat.

“The key in government is customer service,” Callies said. “Think of a developer as your customer. We’re not going to swing the hammer; we need you to. So how do we come together and work for these goals?”

Whether it’s rewriting land-use codes to increase density, passing tax increases, forming metro districts or relying on philanthropy, addressing the region’s growing need for affordable or attainable housing has proved ever more vexing.