Confluence: Colorado River won’t support today’s usages

LOVELAND — Solving issues surrounding water shortages for people and industries dependent upon the Colorado River depend on first discerning what caused the problem in the first place.

And the answer to that is fairly clear: More water is used than the river will supply.

“Climate change is a hard truth we have to face, but that’s just one part of the problem,” said Amy Ostdiek, the section chief of interstate, federal and water information at the Colorado Water Conservation Board. “The key issue is that there are entities on the river that have not accepted that reality and have continued to use the same amount of water despite the declining reservoirs. It’s a matter of how much is going in and how much is going out,” she said.

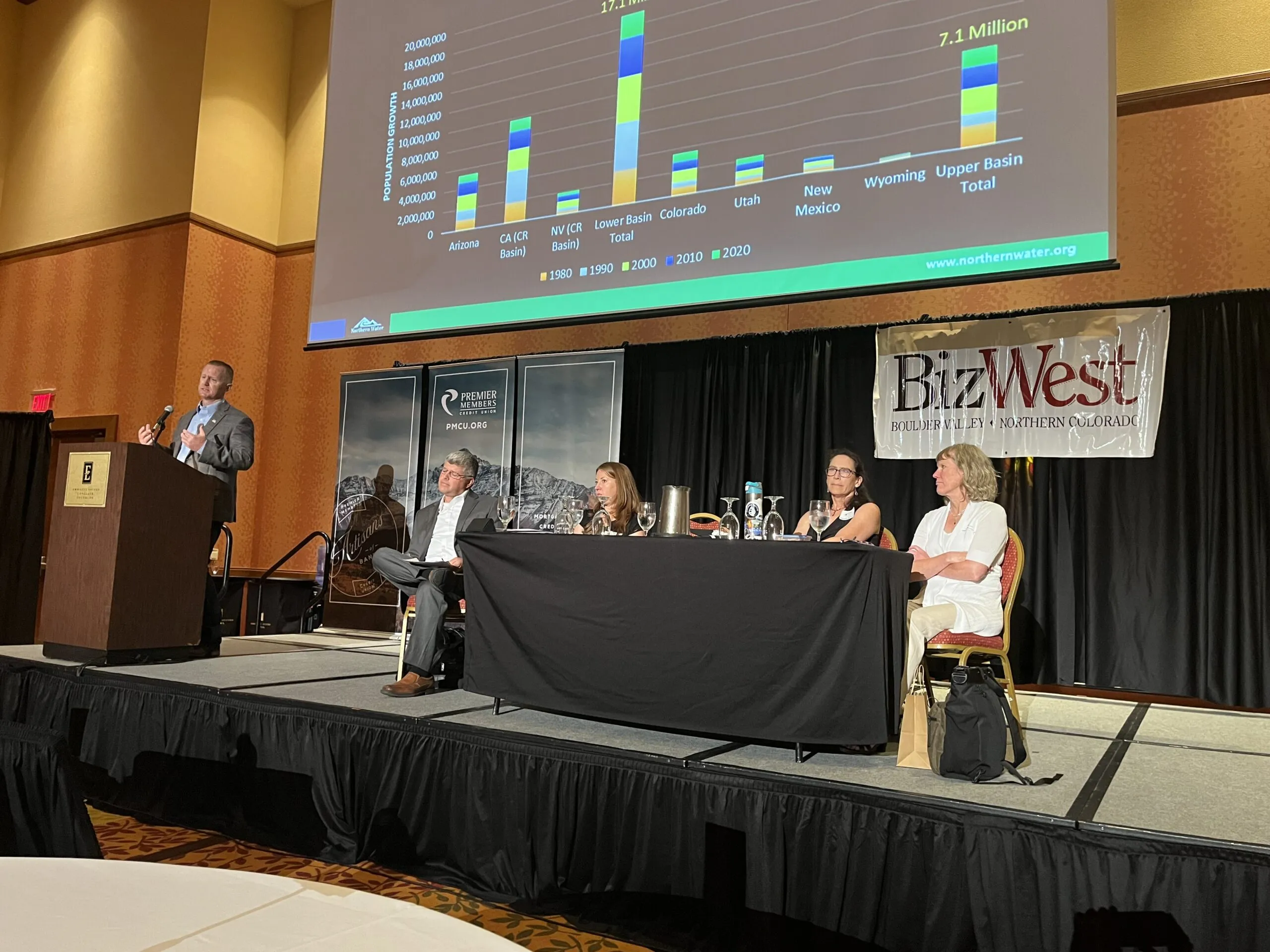

Ostdiek was one of a panel of speakers at the Confluence — Colorado Water Conference who addressed issues surrounding the Colorado River. The BizWest conference was Wednesday at the Embassy Suites Loveland Hotel and Conference Center.

The Colorado River panel was led by Ted Kowalski of the Walton Foundation. Kowalski heads up the foundation’s work concerning the river, “the lifeblood for the Southwest United States. It supports a $1.2 trillion economy, is hugely important for agriculture, for 30 tribal nations, two Mexican states and seven U.S. states,” he said.

In referencing the Colorado River Compact, a 1922 document that divided the river flows equally between the upper basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico, and the lower basin states of California, Nevada and Arizona, Ostdiek said that the compact has always projected allocations greater than what the river would produce, but the basic underpinning of the agreement was that of equity — each basin would have access to half the river’s flows, whatever that might be.

In the upper basin, water usage was dependent upon snowpack. In years when snow was below average, water availability was curtailed to align with supply.

In the lower basin states, the massive Lake Powell and Lake Mead reservoirs were established to capture flow in wet years so that the lower basin states could continue to use what local water rights might suggest should be available.

With long-term drought conditions, those reservoirs have been overextended, setting up a conflict over the river’s available supply.

“The framers (of the compact) intended that the water be divided equally between the two basins. What we’ve seen is that the uses have been far from equal. Lower basin states have been using about 10 million acre feet of water a year. The upper basin has used 3½ million to 4 million acre feet a year,” Ostdiek said.

“The overuse has driven the entire system into crisis. The compact is still in place; we’re not negotiating it,” she said.

In 2022, the federal Bureau of Reclamation said the basins needed to conserve two to four million acre feet of water a year. No long-term plan has come forward to permanently reduce usage of water from the river.

“We have to get the lower basin into check. Water users in the lower basin are not more important than water users in the upper basin,” Ostdiek said.

Kyle Whitaker, water rights manager with the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, continued along those lines. He said usage between the upper and lower basins combined has been fairly consistent at 13.81 million acre feet, while over the past 10 years, the river has produced an average of 11.7 million acre feet. The difference between those numbers has been pulled from Mead and Powell.

He said the 1980s were consistently wet years, but the basins cannot plan for a return to those times. “We have to plan for them not coming back,” he said.

The river, which flows from Rocky Mountain National Park on the other side of the continental divide to the Pacific Ocean, does not exist along the Front Range, but the Front Range is affected because of 24 transbasin diversions that bring about half of the Front Range’s water from the western slope to the eastern slope.

About 25 million more people live in the Colorado River’s basins now than did prior to 1970. It takes about two million acre feet of water just to provide sanitary and drinking water uses to that population growth.

In the upper basin, “we’ve adapted by drying up agriculture. The lower basin hasn’t made that adjustment because of the reservoirs,” he said.

“If we have new demands (for water), it’s going to have to come out of existing demands, because we can’t change the supply side.”

Alexandra Davis, the assistant general manager for water supply and demand for the city of Aurora, said that Aurora water is meeting needs by diversifying its portfolio and forcing changes to how water is used, particularly with landscaping.

The problem isn’t going to go away, she said, because of climate change, which will result in less snowpack, earlier runoff, increased evaporation, decreased soil moisture and more.

Upper Colorado River basin provides 25% of Aurora’s supply. It is fully reusable.

“Every river is dealing with climatic impacts, not just the Colorado,” she said.

Taylor Hawes, director of the Colorado River program for the Nature Conservancy, said planning is essential. “When we are faced with a water crisis, and we don’t plan, there are two losers, the environment and water users.

She offered some thoughts to consider:

- “We are completely connected when it comes to the Colorado river being a statewide resource. Fifty percent of the Front Range’s water comes from the Colorado River.

- “Cities have resources to try new things. They have the money and political will to implement things. Farmers do not.

- “We have to be looking for win, win, wins. We have to find multibenefit projects.

“It is a false choice to say we have to choose farms over fish. Our environment is the canary in the coal mine. How do we keep the environment resilient,” she asked.

“The river that we depend on depends on us to get it right,” she said.

LOVELAND — Solving issues surrounding water shortages for people and industries dependent upon the Colorado River depend on first discerning what caused the problem in the first place.

And the answer to that is fairly clear: More water is used than the river will supply.

“Climate change is a hard truth we have to face, but that’s just one part of the problem,” said Amy Ostdiek, the section chief of interstate, federal and water information at the Colorado Water Conservation Board. “The key issue is that there are entities on the river that have not accepted that reality and have continued to…