Exclusive: Inside Woodward’s months-long quest to build a COVID-19 ventilator

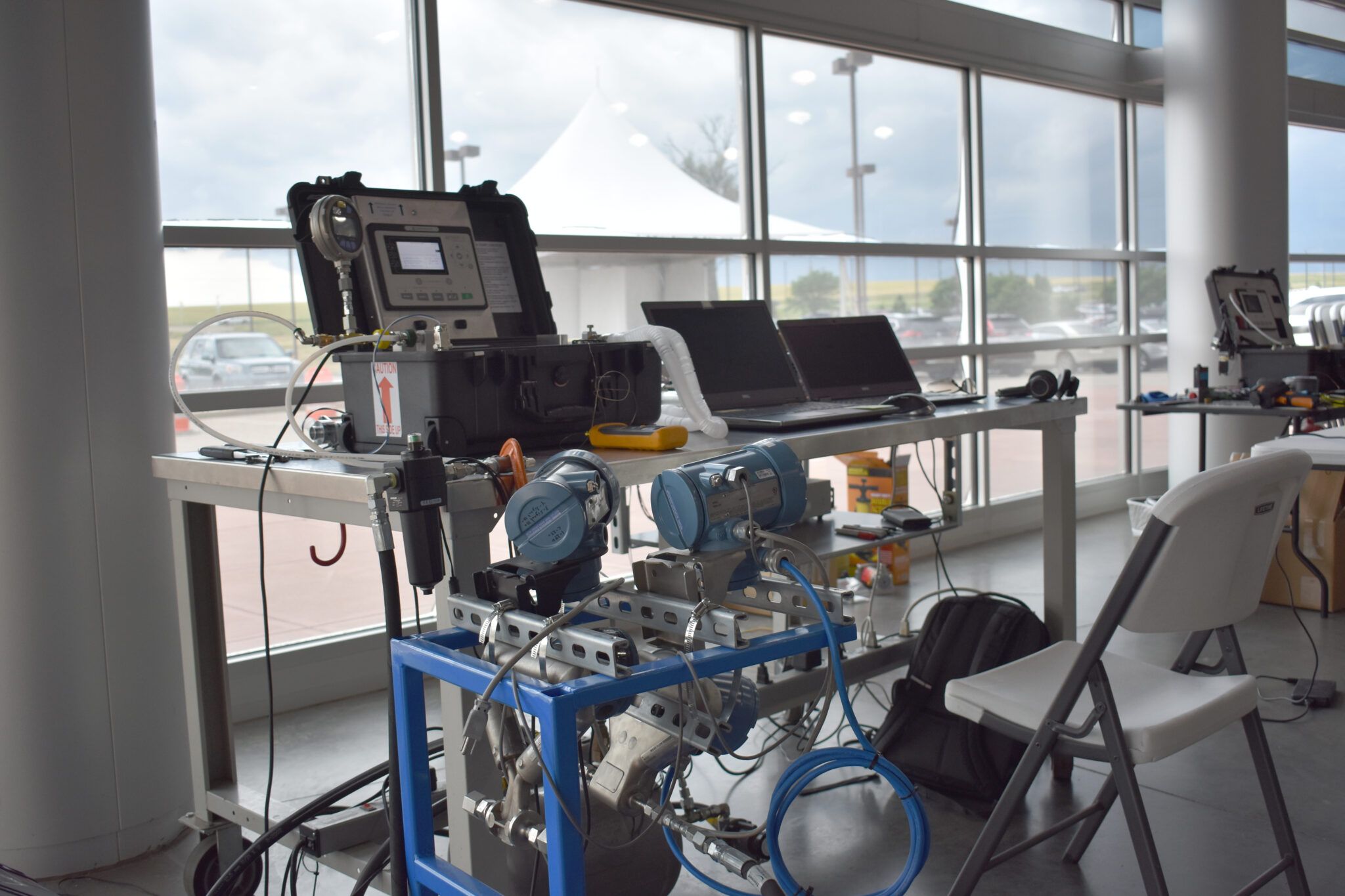

WINDSOR — In the foyer of what used to be a car dealership along U.S. Highway 34, a black plastic tub about the size of a small suitcase pumps air and oxygen into a pair of blue plastic lungs. The faint sound reminiscent of Darth Vader echoes across the room.

It is the sound of potentially thousands of saved lives.

In this building, Fort Collins-based aerospace manufacturer Woodward Inc. (Nasdaq: WWD) is deep in the approval process for turning its existing airplane engine controllers into ventilators that could keep seriously ill COVID-19 patients from joining the more than 120,000 Americans who have died from the disease.

The commonality between airplane engines and human lungs

The concept behind the ventilator is simple: When patients can’t breathe on their own power, a machine will force air into their lungs for them. The four-stroke engine works partially in the same way when a fuel injector sprays a specific combination of air and fuel into a compression chamber.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Within Woodward’s “Aether 100” ventilator, a series of wires and tubes sprawl in and out of the system, measuring pressure and air-oxygen ratios within the lungs inflating and deflating on the table.

Inside, a series of small engines are pumping pressurized air through the breathing tubes, measuring various levels of pressure, flow rate and oxygen to make sure the ventilator isn’t giving the patient too little air, or pushing too much air into a lung that’s beginning to recover some of its power.

A screen in the middle of the case shows off the status of the lungs, spitting out data that the company needs to submit as it tries to land emergency-use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Doug Salter, a Woodward vice president for corporate technology and the project’s lead, said the hardware governing this process is almost the same as the company’s existing generator set control used to determine the amount of air and fuel injected into a chamber. With a few tweaks, this system now measures and injects the correct blend of air and oxygen into the lungs.

“All we’ve done differently is put a different cover over the top of it, and everything else is the same,” he said.

The race to repurpose

As Colorado and much of the U.S. began to order residents to stay home whenever possible in mid-March, an enormous amount of strain came onto the existing supply chains for ventilators and personal protective equipment. While dozens of companies across Colorado shifted production to making cloth masks, face shields and other medical necessities, very few had the capability to develop a ventilator.

In late March, Gov. Jared Polis tapped state universities to see how they could find ways to produce those goods within Colorado’s borders. Bryan Willson, executive director of Colorado State University’s Energy Institute and a longtime collaborator with Woodward, called CEO Tom Gendron and asked the manufacturer to join the effort, Salter said.

Two days later, on a Wednesday, the engineer team first met to brainstorm ways to repurpose their equipment and winnowed the options down to two, which were prototyped. On the next Saturday morning, they had their first prototype ventilator running and going through the first rounds of stress testing.

Salter later reached out to an old Cub Scout friend of his who works as an intensive-care pulmonologist to fine-tune the ventilator’s performance. “He was on the phone with us after a 24-hour shift for two hours on a Sunday night, just answering our questions,” he said.

Woodward also tapped its employees on the other side of the world to help out with the plan. While the engineering team in Colorado slept, the company’s software engineering group in Germany looked at the progress made stateside and developed new software, working straight through the four-day Easter weekend to finish their code.

A week later, Salter gathered the team on a Saturday morning and told them he wanted a usable ventilator ready by 4 p.m. that afternoon. The engineers missed the deadline by three and a half hours, but by then, the machine was ready to go down to the Anschutz campus in Denver for pre-clinical testing on live animals.

Waiting for the feds

Although the prototype was ready in a matter of days, the regulatory process from the FDA has considerably slowed the project. Even under the emergency-use authorizations that the department has widely used to approve coronavirus tests, treatments and equipment at a faster timeline than normal, Woodward’s ventilator has gone through rounds of testing and review to make sure it actually works.

The company started by building to U.S. Federal Aviation Administration specifications for aerospace parts, Salter said. Instead, Woodward hoped that the level of stringency there will be a better early starting point toward reaching medical device-quality rather than shooting for that level in the first go. It also brought in CSU chief medical research officer Heather Pidcoke to advise it on FDA submissions.

Salter declined to say when he thinks the Woodward ventilators will be ready for production and use in hospitals because the FDA doesn’t reveal that information until the product is ready for authorization and until all of the more than 250 specific requirements are met.

“I can’t answer that, but it feels like we’re getting very close,” he said.

The company also expects to receive swift approval for the ventilators in Europe soon after the FDA signs off on it, pointing to a history of reciprocity between aerospace and health-product regulators in the U.S. and the European Union. Apart from a few small differences, if a plane is safe to fly and a ventilator is cleared for use in America, it’s almost certainly ready in the European Union and vice versa.

Woodward plans to build the ventilators in its Rockford, Illinois, plant because the facility already has FDA-approved clean rooms and the approximately 700 employees it has there have been on furlough for months.

Once the ventilator is cleared, Salter said the Rockford plant can build 10,000 ventilators with four weeks of lead time and nine weeks of production. Salter said making more COVID-spec ventilators isn’t particularly useful because they aren’t approved for use beyond the current pandemic. However, if a new pandemic emerges, Woodward and companies like it will have their schematics ready to be tweaked to meet the specific demands of a new disease.

A pivot in aerospace’s turbulent times

Woodward took on this project amid one of the most difficult weeks in its recent history after the widespread drop in commercial air traffic threw the entire industry in disarray. As airlines saw passenger figures plummet more than 85% in a matter of weeks, they were forced to cancel or pause purchases of new planes from the jet-making duopoly Airbus SE and Boeing Co. (NYSE: BA), the latter already struggling to bounce back from the 737 MAX crash controversy.

With new plane orders paused, the ecosystem of aerospace parts manufacturers, including Woodward, saw their revenues from the commercial air segment sputter.

On April 6, it mutually terminated a $6 billion merger with advanced materials maker Hexcel Corp. (NYSE: HXL), citing the need for both companies to focus on themselves. Woodward CEO Tom Gendron agreed to stay on at the helm after initially preparing to join the ill-fated Woodward-Hexcel combination as chairman of the board for a year before retiring.

Days later, it laid off or furloughed 11% of its U.S. staff, with plans to reduce its workforce further by 4% by the end of the year.

Salter said the teams that worked on this project all agreed to join when they were initially recruited, despite the enormous uncertainty of the broader health and economic crisis and the looming threat that they may lose their jobs in the depths of the coronavirus’ deep recession. He said the company is asking only for enough money to recoup the cost of production because it views the project as a public benefit at a time of unprecedented public crisis.

“It was motivating, and I’m going to use the word fun although it seems somehow inappropriate in the situation, but it felt like we were part of something, we are part of something that’s doing something good,” he said.

© 2020 BizWest Media LLC