Direct Primary Care makes wellness pay

Last month, Dr. Cory Carroll, who has been in family practice for nearly  25 years, made a momentous decision that was at once scary and exciting.

25 years, made a momentous decision that was at once scary and exciting.

He dropped Medicare.

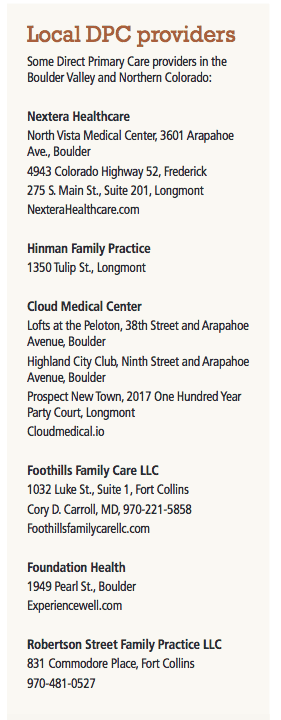

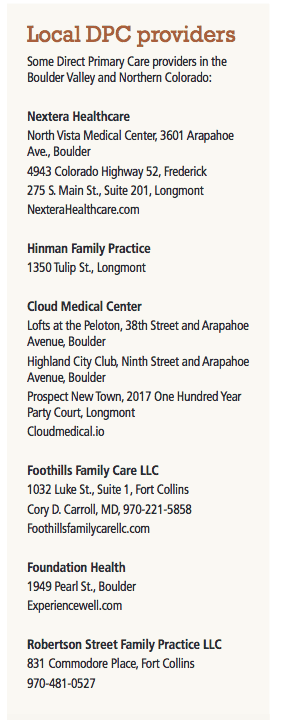

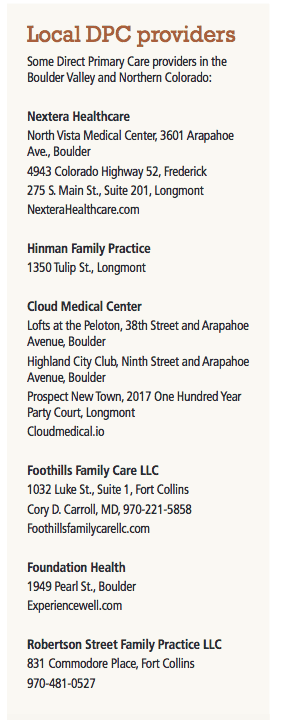

Instead, Foothills Family Care LLC is now joining a growing list of practices that are fully invested in the “Direct Primary Care” model, in which patients pay a monthly membership fee instead of paying for services.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Select your Republic Services residential cart now!

In preparation for Republic Services becoming the primary provider of residential recycling, yard trimmings, and trash, residents should now select the best cart size and service schedule for their household needs.

He began the transition in January by trying a hybrid business plan that still incorporated fees for services but morphed slowly to the new paradigm.

“There was a lot of fear involved. This is a new model,” Carroll said. “When you talk to experts, they say with the typical transition for an established practice, only about 10 to 20 percent of patients will sign up. So as an established doctor, as I was, with a full panel, I would lose on average 80 to 90 percent of patients. There’s the newness, the patients not wanting to pay an extra fee.”

But Carroll was willing to try, and added that it wasn’t a case of teaching an old dog new tricks. “I’ve always been a new dog in an old dog’s body,” he said.

“When I started the transition, I initially had about 175 to 180 patients in Direct Primary Care, about 20 percent. But with the pricing I developed, I needed 300 to 320 patients to break even — to cover salaries for employees and myself and all the overhead. As I was moving my business model this year, I wasn’t spending a lot of effort in marketing, so my growth in the Direct Primary Care practice was stagnant.

“So what I found, with continuing with Medicare, I was not able to meet expenses as we moved into the sixth, seventh, eighth month of the experiment,” Carroll said. “Besides, the current insurance model was more burdensome, regulatory and frustrating, and for a small solo-doctor practice it was impossible to manage.

“So I could either scrap it all and go back to the insanity or dive in full force.”

He finally realized he had no choice but to cut the cord.

“The day before I needed to give Medicate my opt-out notice, I did it — and it was a good decision.”

What happened?

“It went quite well,” Carroll said. “When I gave notice to my Medicare population, there was some anger, some frustration — but surprisingly, and graciously, many of my Medicare patients understood the frustration and wanted to support and maintain a presence in my practice.”

He retained about 25 percent of his patients including half his Medicare clients, and his patient rolls now are approaching 300.

“It’s still novel, different, perhaps scary — especially to providers,” Carroll said, “but it allows me to be much more focused on patient care.”

The insurance system required face-to-face encounters between doctors and patients, Carroll said, but he can now talk with them in ways that are convenient for them — including Facetime or Skype. “They get to dictate, up to a point, how I can serve them,” he said. “There’s no reason for me to physically force them to come to my office. I had two 20-minute phone conversations with patients today.

“I still schedule it,” he said. “It’s an appointment for me, but instead of a waiting room of people who have had to take off work and sit for God knows how long out there, they can do it from home. It’s exciting because it’s a better way to take care of patients.”

Under the Direct Primary Care models, Carroll’s patients pay a varied monthly fee: $15 for patients younger than 18, $40 for ages 18 to 39, $55 for those 39 to 65, and $70 a month for those older than 65. There’s a 15 percent discount for couples and families, one month free if a year’s service is purchased, and a 10 percent discount if patients meet health criteria such as having an ideal body weight, being a nonsmoker, or eating a plant-based diet.

“I’ll likely increase that to 20 percent as more patients succeed,” Carroll said.

The new model allows Carroll to “focus a lot of my practice on prevention — how to avoid type 2 diabetes, hypertension.”

It also works better for his bottom line, Carroll said.

“If my patients are healthy and I only make money if they come to me when they’re ill, I don’t make a lot of money,” he said. “There’s no incentive to transition from sick to health. I still get compensated for this work, whereas with the fee-for-service model you lose money.”

That payment model isn’t rigid for Direct Primary Care practices, which adds an extra bit of consumer-friendly competition to the field.

“I’ve heard at different conferences that if you’ve seen one direct-care office, you’ve seen one,” said Ginnie Meyers, wellness partner at Foundation Health in Boulder. “Everyone’s a little different.”

Foundation charges $175 a month across the board or $150 if payment is made quarterly, plus a $25 discount for dependents. The practice still supports those with insurance, especially to cover major procedures its clinic can’t do.

“Companies also might be interested in having this as a supplement to whatever they have,” Meyers said. “Brokers are setting up an insurance plan that will look exactly the same as a typical fully insured plan — with deductible, copays, a gamut of bells and whistles – but the difference is that it’s a partially self-funded plan. The employer would pay the doctors through a third-party administrator up to a certain amount, whatever they’ve budgeted. If they don’t pay that amount, it goes into an escrow account — a ‘claims reserve.’ If they don’t use it, they get it back. It’s a way to reward employers for getting healthy.

“We’ve had a lot of companies saving a lot of money. We had one client group of 60 who got $52,000 in claims reserve back.”

But with other practices also using the model, “we have to be different from your primary doctor — longer visits, more one-no-one, focus on general well-being. Every part of your life is taken care of.”

Most phenomenally in terms of what American patients are used to, she said, “most visits might last anywhere from one to three hours. Patients are in the waiting room less than five minutes and then in the clinic as long as they need to be.

“We’re really structured in a way that providers can practice medicine in the ways they really thought they were going to when they went to medical school.”

Whereas a typical primary-care office might have 2,500 to 4,500 patients per provider, Meyers said, “we cap our patient load at 1,000 among all our providers.” After making the transition in February 2014, she said, “We broke even in under two years.”

Both Meyers and Carroll expressed frustration as rates of obesity, diabetes and hypertension increase in the country.

“We were treating symptoms, not helping patients understand that what they eat is the main driver of disease,” Carroll said. “The medical model is still enmeshed with pharmaceutical solutions.

“I was a practicing engineer before med school,” he said, “and the phrase ‘We don’t know’ is frustrating to an engineer because we needed to know how something worked before we built it. That’s why we have to understand the critical importance of what you eat and how your body exists.

“That’s what we’re doing now. We give them facts and evidence, and then their diabestes, blood pressure, cholesterol all get better. Direct primary care allows me to emphasize that, 100 percent, and still get reimbursed.

“This model moves us away from that ‘Here’s your pill, here’s your next appointment’ scenario.”

For catastrophic care, plans such as Liberty Direct are available, he said. It’s not compliant with the Affordable Care Act because it doesn’t cover some pre-existing conditions, but it still meets Internal Revenue Service requirements that allow taxpayers to avoid the penalty the ACA charges.

“It’s a nice option for small businesses struggling with insurance costs,” he said. “They will count that as insurance.”

Carroll acknowledged that with a monthly fee covering all services, there could be some abuse — but he figures it balances out.

“Some may need more care while others need less,” he said. “If I’m smart I can take care of all of them, make a living and be sustainable. I’m very satisfied with my financials.”

He figures he could hire an exercise coach, host group yoga classes and bring in a chef who teaches healthy meal planning in the office.

“I told a patient today that if I’m successful, we’ll take him off three drugs in the next year, which basically could pay for my monthly fee,” Carroll said. “As they get healthier, I’m going to charge them less money.”

Last month, Dr. Cory Carroll, who has been in family practice for nearly  25 years, made a momentous decision that was at once scary and exciting.

25 years, made a momentous decision that was at once scary and exciting.

He dropped Medicare.

Instead, Foothills Family Care LLC is now joining a growing list of practices that are fully invested in the “Direct Primary Care” model, in which patients pay a monthly membership fee instead of paying for services.

He began the transition in January by trying a hybrid business plan that still incorporated fees for services but morphed slowly to the…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!