Lessons learned

Flood, chaos, trauma yield to silver linings

Hard rain that fell in broad sheets across the northern Front Range foothills and plains on Sept. 8, 2013, was most welcome.

The showers spawned by a storm system that streamed in from the southwest quenched a landscape that had been left parched and cracked by several weeks of heat and drought. The deluge continued over the next three days, blowing away nearly every regional rainfall record. Then, by Sept. 11, all those blessings became curses as the land absorbed its limit and began spilling the rest just as the heaviest rains arrived.

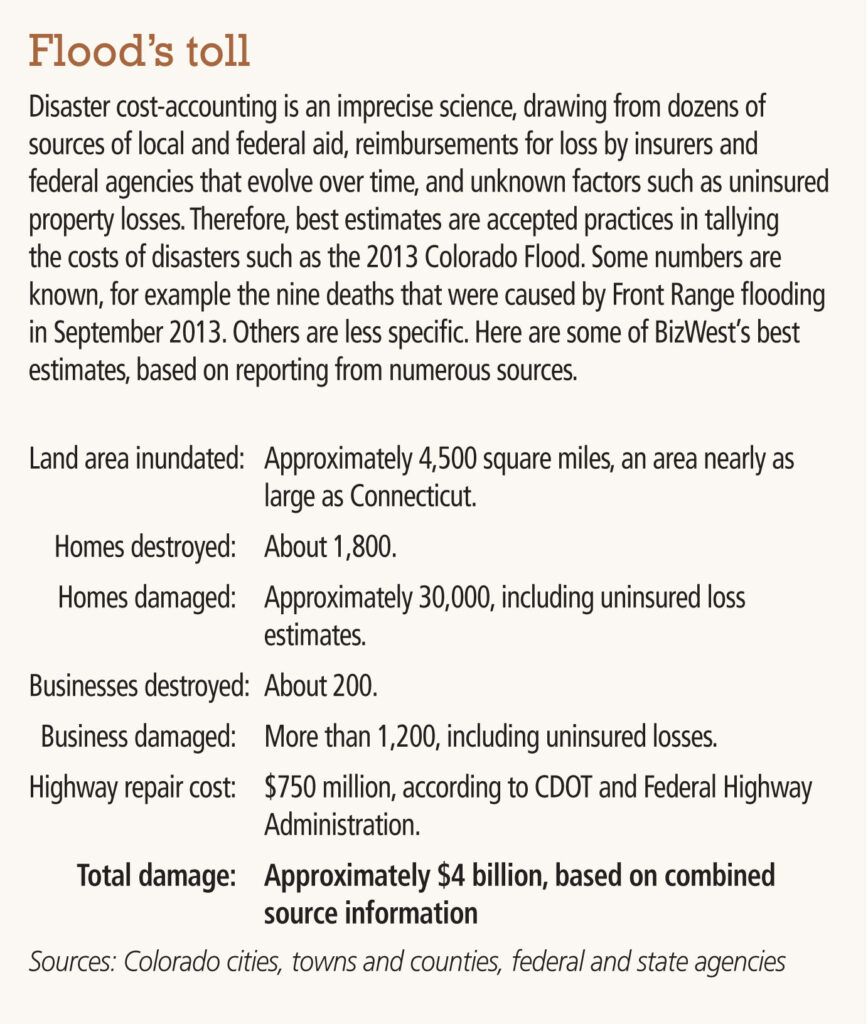

The result in some locations was cataclysmic. Creeks and rivers normally placid during late summer became roaring torrents that gushed through canyons and swept across the bordering plains. Fast-flowing water inundated hundreds of square miles of land, killed nine people, ripped apart homes and businesses and destroyed roads, utilities, parks and anything else in the rushing water’s way.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Boulder, where 18 inches of rain fell during the seven-day storm, was first to feel the fury. A man and woman, both 19, died Sept. 11 while trying to escape their Subaru that had become mired in a slurry of mud, boulders and debris that fast-moving floodwaters had shoved down a street on Boulder’s northwest edge.

Further north, the town of Lyons was being scoured by St. Vrain Creek as it carved a 400-foot-wide gorge through the town on Sept. 12. The St. Vrain then surged eastward through Longmont where it damaged or destroyed hundreds of homes and businesses.

Following the same schedule, the Big Thompson River, flowing at 500 times its normal seasonal flow, brought similar peril to Loveland. After tearing through its narrow lower canyon, killing two women whose homes were splintered by the rocks and trees the river carried, the Big Thompson spread across Loveland, spilling over roads, swamping bridges and cutting the city in two.

All that water, from the multitude of rivers, creeks, streams and smaller drainages that empty from mountains to plains eventually reached the South Platte River. Towns and cities such as Johnstown, Milliken, Evans and parts of Greeley, as well as Eastern Plains towns including Fort Morgan and Sterling, were overwhelmed by flows that no one could have imagined.

Unexpected benefits

During much of the past decade, the tasks of restoration, recovery and financial survival kept many Northern Coloradans from seeing a brighter outcome from all the wrenching trauma of the 2013 Flood and its $4 billion toll. However, a broad consensus today seems to hold that the region is better off for having endured it.

“Of course, the destruction, the loss of life and loss of property were terrible,” city of Loveland civil engineer Chris Carlson said in late August on a walk through one of the flood’s battle zones. “But the changes that have occurred here because of the flood have been so good for the community.”

Carlson described those benefits as he stood in front of the Wilson Avenue bridge over the Big Thompson in West Loveland. As the result of one post-flood project, the street’s southern approach to the bridge was raised three feet, at a cost of $4.1 million, to ensure that a future big flood would not present the same consequences that the 2013 event did.

Once public and private insurance claims had been settled, and FEMA had closed the books on its complicated reimbursement process for cities and towns, irrigation districts, utilities, businesses and private property owners, Northern Colorado communities turned attention away from recovery and rebuilding.

They focused instead on solving long-standing problems that had been laid bare by the receding flood and turned their planning staffs loose to re-think the ways cities, towns and counties could be made more resilient in the face of natural forces.

Related stories

- Mountain towns rebuilt themselves

- Sylvan Dale going strong a decade later

- Inn of Glen Haven’s new owners preserve a flood of memories

Best-practice report

Local governments and community leaders got plenty of advice along the way. In 2014, much of it came from the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Land Institute, a nonprofit group that advocates best-practice policies on land use issues.

The ULI assembled a nine-member panel — including architects, engineers, planners, lawyers, economic development experts and finance gurus from cities across the U.S. — who spent five days focusing on ways Larimer County communities could better prepare for natural disasters. While their focus was limited geographically, the group’s findings had relevance for all who had endured the ravages of the 2013 Flood.

Panel organizer Jim Heid, founder of California planning, design and real estate consulting firm Urban Green, described his group’s mission as “a daunting challenge, because of the enormous scale, complexity of issues and unique personalities of each of the jurisdictions we worked with.”

Among the 75 community leaders and subject experts that the panelists interviewed was Loveland engineer Carlson, who is credited in the ULI report for one of its core messages.

“The typical approach to flood mitigation is that you have to build everything harder, stronger, straighten the river, build levies, keep the river from getting out of its banks,” Carlson said. “Sooner or later, you’re going to get a storm that’s going to topple all of that. In New Orleans, it was Katrina. For us, it is what we saw in 2013.”

‘Let rivers be rivers’

The ULI report picked up a tagline from Carlson, a four-word mantra that the panel said should serve as a guide for any post-flood thinking: “Let rivers be rivers.” Panel members said the message was equally simple. “Work with the forces of nature, rather than against them.”

While the ULI advice was not directed specifically at Boulder County as it pondered ways to change its post-flood landscape, planners there intuitively put the same ideas to work. Longmont, for example, integrates some of that philosophy into its “Resilient St. Vrain Project” — or RSVP.

Havoc caused by the flooding river was a shock to the city, and some of the consequences were heart-breaking. More that 200 single-family homes that had been built in the 100-year floodplain were no match for 2013’s 500-year flood. By Sept. 13, after residents evacuated, most of those houses were rendered uninhabitable, and their contents destroyed.

The Resilient St. Vrain has so far spent $80 million from a mix of funding sources, and will add another $20 million for projects on the near horizon, to meet its resiliency goals. Along the way, the St. Vrain’s corridor through the city has become much more of an amenity, much less of a threat.

“This community had turned its back on the river for many years,” said Sean Cronin, executive director of the St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District, the water-management agency whose jurisdiction makes it a close partner with the city of Longmont.

“We didn’t consider how the stream needs to function, or recreation, or the environment, or the ways people interact with the river. All those things were neglected.”

RSVP has transformed parts of the St.Vrain corridor into some of the most beautiful and heavily used parts of the river’s corridor. The St. Vrain Greenway hard-surface trail carries cyclists and pedestrians along an eight-mile stretch eastward between Golden Ponds and Sandstone Ranch nature areas.

The 52-acre Dickens Farm Nature Area, completed in 2018, invites users of tubes, kayaks, paddle boards and other non-motorized craft to enjoy the river in the wettest possible ways. On warm summer days they flock by the hundreds. “I’m just thrilled with the ways people connect with the river now,” Cronin said.

‘Had to be done’

Rural roads, streets and highways throughout Northern Colorado were ravaged by the 2013 Flood, and some economic development advocates say the flood pushed needed projects ahead.

Loveland Area Chamber of Commerce President and CEO Mindy McCloughan said the I-25 Express Lane Project, now in its final stages, would still be just in blueprints if not for the flood.

“That was our big wake-up call,” McCloughan said, recalling the Sept. 12-13, 2013, closure of Interstate 25 in both directions by the flooding Big Thompson. “I think everybody in the region then knew that something had to be done.”

Hard rain that fell in broad sheets across the northern Front Range foothills and plains on Sept. 8, 2013, was most welcome.

The showers spawned by a storm system that streamed in from the southwest quenched a landscape that had been left parched and cracked by several weeks of heat and drought. The deluge continued over the next three days, blowing away nearly every regional rainfall record. Then, by Sept. 11, all those blessings became curses as the land absorbed its limit and began spilling the rest just as the heaviest rains arrived.

The result in some locations was cataclysmic. Creeks and rivers normally placid…