‘We must protect this house!’

Intellectual property, copyright defense a must for Boulder Valley, Northern Colorado companies

So you’ve launched a company, found your customer base, mastered the nuances of your supply-chain and retail strategy, and built a name for your brand that connotes quality.

Then you’re perusing Amazon and come across a seller you’re unfamiliar with selling a product that looks suspiciously familiar.

Congratulations, you’ve made it to the big leagues — your product has been counterfeited.

SPONSORED CONTENT

In innovative economic environments such as Northern Colorado and the Boulder Valley, companies from consumer-packaged goods manufacturers to pharmaceutical firms regularly experience situations like this, and vigilance is required to protect trademarks, copyrights, brands and other types of intellectual property.

“Intellectual property is a game of cat and mouse sometimes,” said attorney David Kerr, co-founder of Berg Hill Greenleaf Ruscitti LLP’s intellectual property practice group.

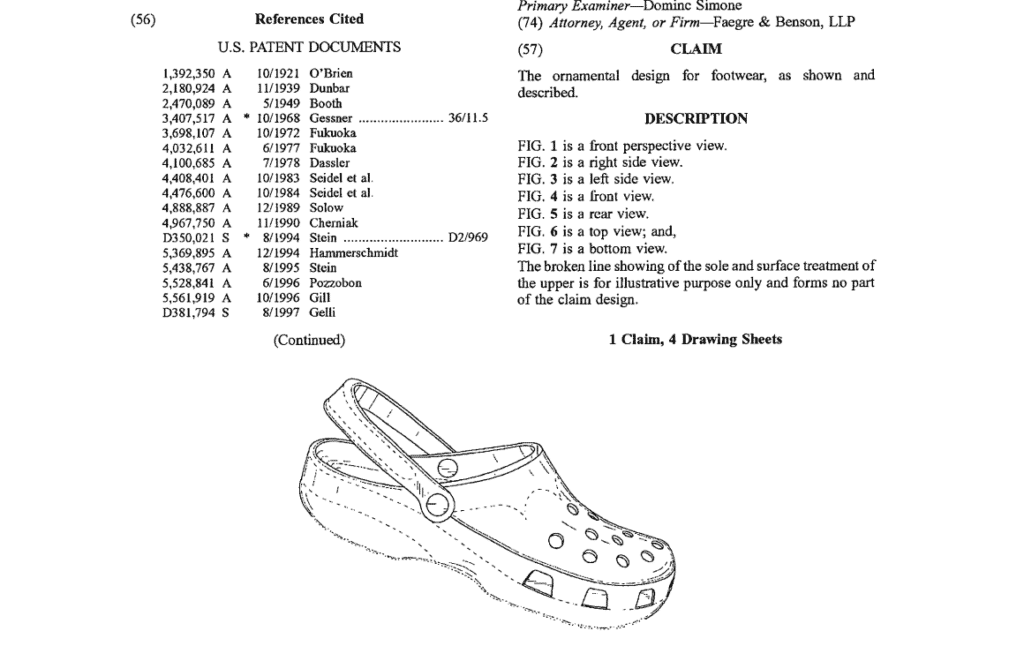

In July, Broomfield-based casual footwear maker Crocs Inc.’s (Nasdaq: CROX) won judgments against copycats USA Dawgs Inc. and Double Diamond Distribution Ltd. of $6 million and $55,000, respectively, bringing to an end a copyright-infringement case that had been kicking around the U.S. District Courts, appellate bodies and the U.S. International Trade Commission since 2006.

“We are fiercely protective of the Crocs brand and our iconic DNA. We have zero tolerance for infringement of our intellectual property rights or for anyone who tries to benefit off the investments that we have made in our brand,” Crocs chief legal officer Daniel Hart said when the judgments were issued.

For popular brands with products that are fairly simple to replicate, experts say it’s only a matter of time until knock-off artists come knocking.

“Inevitably, other enterprising individuals look at the success of this thing and think, ‘Well, this is pretty low-tech’” and can be replicated and mass produced, Colorado State University marketing professor Jonathan Zhang said. “The barrier to entry is fairly low, and you’re likely to get a lot of ‘me-too’ products.”

Kerr recalled a past client whose company manufactured in Asia. The firm contracted with a factory that would pump out a million units of product for the client and then another half-million units “to be sold out the back door.”

He added: “If they don’t have good relationships with manufacturers and good controls in place … they can absolutely be taken advantage of.”

The rise of e-commerce giants such as Amazon and Alibaba has further complicated the situation for counterfeit victims by providing a somewhat lawless online marketplace for knockoffs.

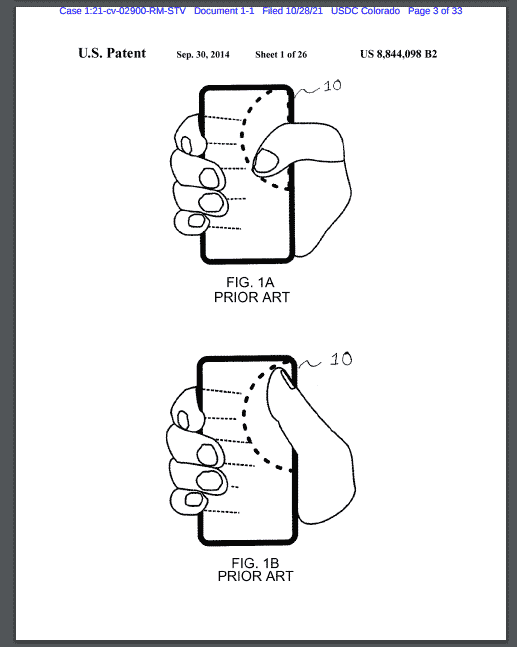

Last year, Otter Products LLC and TreeFrog Developments Inc., both Fort Collins companies, sued the operators of a Florida company that allegedly used Amazon fulfillment centers to store and supply infringing products, which in addition to real new and used Otter products also include knockoffs that bear the Otter trademarks.

In 2020, Popsockets founder David Barnett told a U.S. House Judiciary antitrust subcommittee that Amazon was “strong-arming” the company and failing to remove products that impersonated its wares.

Barnett told the subcommittee that PopSockets’ brand is harmed by the “enormous amount” of copycat products being sold on Amazon by third-party vendors, claiming that his company was fending off more than 1,000 fake and pirated items a day.

“There’s a threat that their actions are diluting our strength of brand,” he told lawmakers. “Imagine if [Italian fashion company] Versace sold stuff on Amazon for 50 cents. It would make customers say, ‘Wait a minute, I thought Versace was a luxury brand,’ and have negative feelings about the brand.”

Zhang said, “When these ‘me-too products’ get too big for comfort, then it makes economic sense for a [company such as] Crocs” to push back with litigation.

Of course, it’s not just consumer goods companies that fight over intellectual property, and local companies aren’t always on the plaintiffs’ side of the equation.

Brickell Biotech Inc. (Nasdaq: BBI) in 2020 forked over $1 million in cash and an undisclosed amount of stock to settle a lawsuit with Miami-based Bodor Laboratories, which alleged bad-faith practices related to a licensed anti-sweating treatment, including claims that Brickell tried to patent the technology as its own.

“The U.S. patent system is certainly the most robust and most predictable patent system in the world” for both obtaining and protecting intellectual property, Kerr said. “If you want to enforce a patent, the U.S. courts are a great place to do it. There’s a lot of precedent, the courts are familiar with it and there are predictable procedures.”

The concept of “first to invent” is important in the U.S. patent system, Kerr said, especially for biosciences or technology products as multiple companies are often chasing the same outcome — an anti-sweating treatment, for example.

This makes it critical for innovative companies “to file their patents before their competitors can.”

The process is complicated by the fact that it often takes years for patent applications to be approved.

But once the patent is granted, companies and their attorneys shift their focus to protecting it.

Patent attorneys can also help companies research the types of IP that their competitors possess in order to avoid infringement minefields.

“Most companies that rely on intellectual property expect others to respect their patents and intellectual property in the same way they respect other people’s patents and intellectual property,” Kerr said. “Most people don’t want to be sued, and they don’t want to have to sue people.”

This patent surveillance process serves not only defensive goals but can allow companies to go on the offense to exploit corners of the market where no IP exists.

“That’s the really strategic aspect of intellectual property law that we spend a lot of our time dealing with,” Kerr said.

Most developed countries around the globe typically have similar systems to the U.S., while developing nations often have less established procedures for protecting patents.

China, with its authoritarian regime and status as “factory of the world,” is something of the 800-pound gorilla in the room during discussions of overseas intellectual property.

In 2018, Popsockets identified 14 Chinese firms that were making knockoffs. The company took their claims to the U.S. International Trade Commission, which then issued a general exclusion order, permitting the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency to seize imported counterfeit products.

“China has a reputation for not being a place where it is easy to enforce your IP,” Kerr said. “That reputation is certainly well earned, but it’s changing.”

As the Chinese economy has evolved in recent decades and companies there begin to amass their own collections of intellectual property, “they begin to realize the importance of respecting other people’s IP,” Kerr said.

Once Chinese firms begin having their own products and ideas copied, “they suddenly have a newfound respect for the system,” he said.

But regardless of movement in the right direction among certain global counterfeiting hotspots, “there are always going to be some companies out there with a business model of cheating, stealing and taking IP,” Kerr said. “That’s the price of doing business sometimes.”

Protecting intellectual property is often about more than combating counterfeiters; it’s about protecting the very essence of a company’s identity: its brand.

Branding is not a new phenomenon that came to prominence along with the rise of capitalism and the industrial revolution several hundred years ago.

Pre-industrial examples of brands include, well, the literal brands that herdsmen and women used to identify their livestock from others, as well as names used by French regulatory bodies to differentiate types of wine by quality of grape and region of origin.

“People have always needed some sort of signal of quality to make decisions,” Zhang said.

That said, the concept of branding has evolved to potentially include a series of rather vague attributes. But the purpose remains the same.

“A brand is a name, a logo, a set of colors,” Zhang said. “But really what it is is a promise that a company makes to a consumer about its quality, its performance, its durability.”

Companies, like the operators of branded livestock ranches before them, have an incentive to protect their brands and therefore their reputations.

“Copyright infringement or intellectual property infringement is very detrimental to the target because [another entity] is freeriding on the goodwill that the brand presents,” Zhang said.

This concept reared its head locally in 2020 when Boulder-based sports nutrition powder maker Skratch Labs LLC sued Scratch Kitchen, a new Boulder take-out and delivery restaurant concept from Delivery Native LLC and natural and organic industry veteran Michael Joseph, alleging that the eatery’s name is too similar.

By adopting a similar name, Scratch Kitchen’s owners have “caused actual confusion and are likely to continue to cause confusion and to deceive consumers and the public regarding the source of defendant’s products and to harm the distinctive quality of Skratch Labs’ marks,” according to the trademark-infringement lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court in Denver.

Joseph told BizWest at the time that he believes Skratch Labs’ suit is a frivolous attempt to pry a settlement payment from Scratch Kitchen.

“This is bullying,” Joseph said. “And it’s bullying during a pandemic when small businesses are suffering.”

The case was settled this year.