Exiting the exchange: Insurers fleeing health-care exchanges nationwide

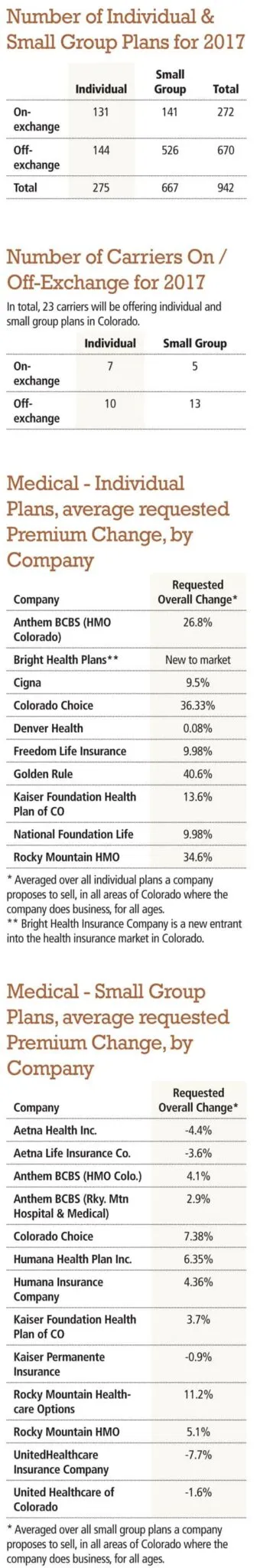

Health-insurance exchanges in Colorado, and across the country, haven’t quite worked out as expected since the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was fully implemented in 2014. Some large insurers have pulled out of the individual exchange market for the 2017 benefits year, and others are asking the Colorado Division of Insurance for as much as 40 percent increases to the premiums they charge to pay for expected increases in costs.

Health-insurance exchanges in Colorado, and across the country, haven’t quite worked out as expected since the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was fully implemented in 2014. Some large insurers have pulled out of the individual exchange market for the 2017 benefits year, and others are asking the Colorado Division of Insurance for as much as 40 percent increases to the premiums they charge to pay for expected increases in costs.

As changes are being set for 2017, it is clear that many individuals in the state will lack choice…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!