Women, especially mothers, face pandemic-related setbacks

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Fort Collins business owner Cindy Skalicky found herself grateful her children are above age 11 and that she didn’t need child care. Yet, like many other female professionals, she had to adjust to the balance of her home and work lives.

“I felt a consistent rub to manage my time better because my kids were home all the time,” said Skalicky, owner of a home-based boutique messaging firm, On Point Communications, about her four children, ages 12, 14, 15 and 17. “I felt this gravitational pull to be increasingly attentive to them because they were here all day long.”

Skalicky had to figure out how to blend her home life with her work life and her children’s social lives without “knowledge of how to create boundaries in this strange time,” Skalicky said. She needed to spend time with her kids and while doing so not think about work, while also keeping her career “alive and thriving” when she wasn’t connected with those she works with — she helps individuals and corporate teams with end-to-end presentation skills, she said.

SPONSORED CONTENT

On Point Communications took a big hit in the second and third quarters of 2020 when Skalicky’s in-person presentations and training were cancelled and her clients could no longer engage in public speaking; she responded by pivoting to reach her target audience through virtual webinars and training. This while her husband’s business had to shut down for one month and she became the only one in the family who could earn an income.

“I wanted to stay engaged with people. That took time from my kids,” Skalicky said, adding that she felt guilty as a mother who works.

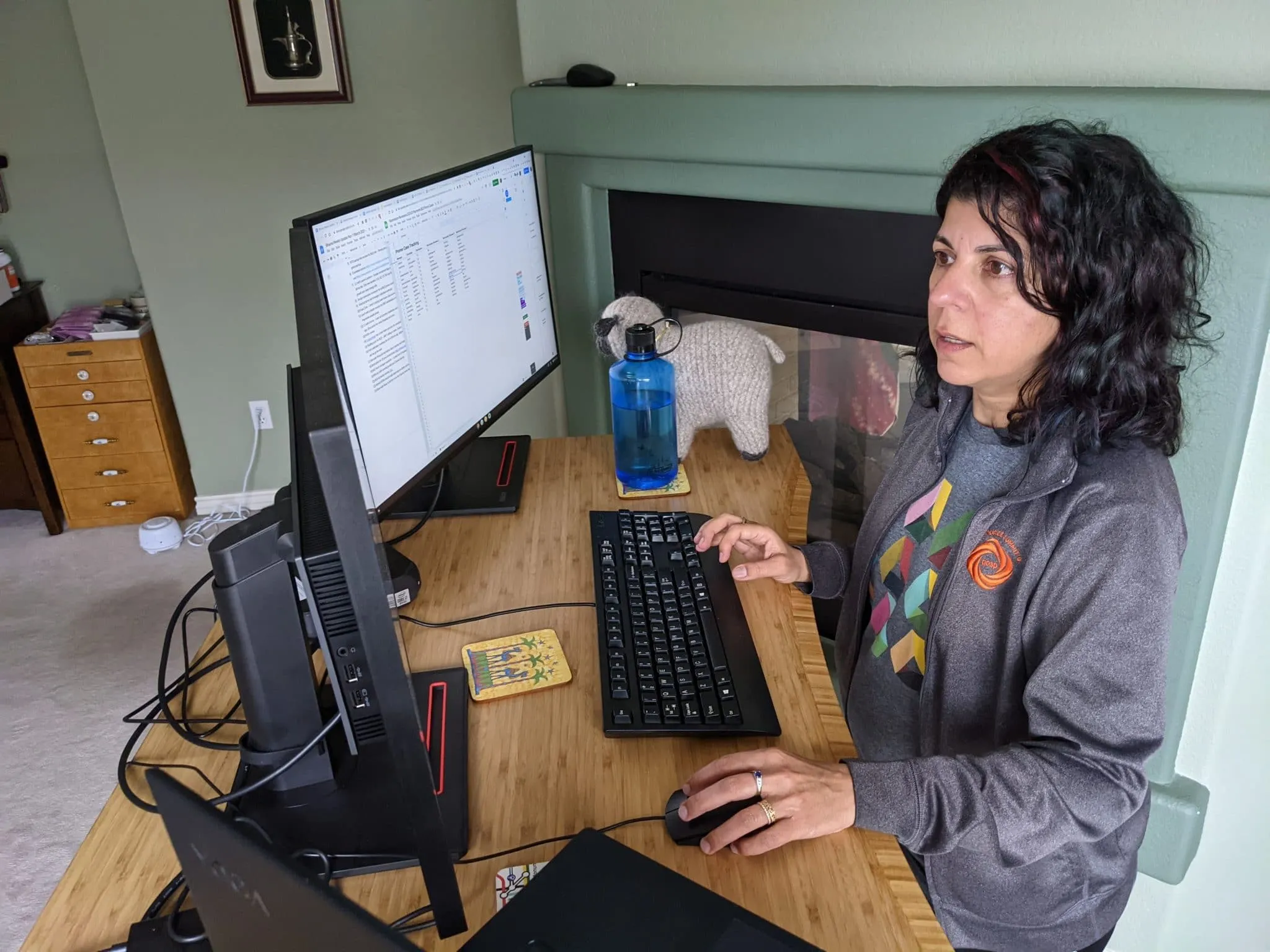

Bhavna Chhabra, site director and technical team engineering director at Google Boulder, also experiences feelings of guilt when she cannot spend as much time as her 2-year-old daughter would like her to, now that she is working from home. She also has a 17-year-old in high school and a 20-year-old in college.

“While I have my husband, who’s a stay-at-home dad right now with our 2-year-old, quite often she wants mommy. She knows I’m in the house,” Chhabra said. “I feel obligated to go to her.”

Chhabra, a Boulder resident who speaks about and mentors women in the workplace, has seen the effects of the pandemic on women at Google Boulder and at other companies. One of her coworkers quit to be at home with her child, and for others, the larger share of child care and housework fell on them, she said.

“Because of COVID, child care is not available or families are not comfortable. That means that quite often families are juggling a lot without external help and without child care,” Chhabra said.

If families are working and engaging in online learning at home, that adds to the burden of household chores with the addition of cleaning, cooking and other housework created by more time spent at home. Chhabra, for instance, used to hire a house cleaner but because of concerns about the virus is doing her own cleaning, plus cooking more meals that used to be eaten at school and the office.

“There are so many men who are just as engaged and available for their children, but typically I see a lot of women carry that burden,” Chhabra said.

Anecdotally and not just related to the pandemic, Chhabra has seen women opt out of the workplace to care for their children; when they return to the same or a different company, they are behind and have lost time for furthering their careers, she said. Plus, their skills may have atrophied, she said.

“The more you’re missing work hours, the less time you have to prove what you can do,” Chhabra said.

When Chhabra’s two oldest children were younger, she quit her tech job in Boulder to raise them, but when she came back two years later, her peers had moved on in their careers into lead and management positions, she said.

“I felt so torn between my career … and being a good mother,” Chhabra said. “Because of my experience, I have so much empathy for what women are going through.”

Peggy Shell, chief executive officer and founder of Creative Alignments Recruiting Reinvented in Boulder, isn’t sure if she wasn’t her own boss if she’d be able to meet a boss’s expectations. She juggles her work with care of her two children, ages 8 and 14, who have engaged in remote learning for the past year except for one month in the fall.

“I work a lot but it’s very spotty and with interruptions. Now my work day is the whole day with lots of breaks for meals and help with homework,” Shell said.

One of Shell’s female employees, though able to work remotely, temporarily left the company to provide child care for her two children under age 5 and now is back on a part-time basis. She missed out on a year of growth and isn’t eligible, at this point, for promotional opportunities, Shell said.

“The problem is you take women out of the workforce for a short amount of time and the opportunities are not in front of them. … They aren’t in the position they might have been to get a promotion,” Shell said. “They have to find a similar job that’s lateral or even a step backward. They’re not going to move forward.”

Anecdotally, Shell has seen a number of women through the pandemic take a step back in the workforce, either leaving by choice or through a job loss. She hopes that when they return, employers will provide flexible hours and opportunities for job sharing and remote work when possible, she said.

“We’ll see if it’s a short-term blip, or if we’ve taken a huge step backward. I think it’s the latter,” Shell said.

As it is now, the workforce has lost a large number of women post-pandemic with a recent statistic showing a statewide loss of 20,000, said Tatiana Hernandez, chief executive officer of the Community Foundation Boulder County. Women are losing or leaving their jobs, as well as cutting back on their hours, to provide child care and to become their children’s teachers when schools operate virtually, she said.

“It’s a disproportionate effect on women in the workforce than we’ve seen before,” Hernandez said. “You’re seeing the effects most on working mothers and particularly on moms who are low or moderate income.”

Nearly half of all working women, or 46%, worked in low-wage jobs pre-pandemic in 2018, Hernandez said, quoting from the American Community Survey. During the pandemic, job losses occurred in the hospitality, leisure and restaurant industries, which have a higher number of women than men, while jobs in frontline industries brought on new stressors, she said.

“For those women who were or are working in what we consider frontline industries, whether that be in education or health care, they are stressed out and overburdened and may be looking at career changes,” Hernandez said.

The resulting long-term effects on women’s economic and social mobility post-pandemic will have what Hernandez refers to as “a long tail.”

“The long tail, when you combine job loss, lack of child care and teaching responsibilities that fell predominately on women and the domino effect on housing stability, mental health and overall financial wellbeing, women, and in particular working moms, will need incredible support just to get back to their pre-COVID levels of stability,” Hernandez said. “Pre-pandemic, a large number of women, 46% of women, were barely making ends meet. It will take a lot to get them back to barely making ends meet and then to thriving.”

The statistics are even worse for women of color, Hernandez said.

“The pandemic made a pre existing racial inequality for working women even worse,” Hernandez said. “For me and a lot of us in the social sector, how we build programs that target and support particularly women of color in our recovery efforts are going to be particularly critical.”

Whitedove Gannon, a mentor and the founder and host of the FEMnation Podcast, has seen the entrepreneurs and professional women she works with readjust their schedules to accommodate their home lives, fitting work around online learning and more meals at home, she said. At the same time, many of the women faced a lull in their business at the start of the pandemic and then had to pivot from one-on-one consultations to virtual groups, since there was a default to virtual, she said.

“Some lost clients because they wanted one-to-one,” Gannon said, adding that though it took time, they gained other clients who could be reached virtually. “In the evolution process, it created opportunities in another spectrum they hadn’t realized they’d grown to yet.”

Ann Clarke, founder of Colorado Women of Influence, hears from dozens of women about how the pandemic has affected them personally and professionally through in-person discussions hosted by her nonprofit, Zoom meetings, neighborhood get-togethers and her chamber of commerce involvement. Many of the women, who typically don’t complain, have little praise for leadership’s responses to the pandemic, particularly “how ignorant our leaders are locally and regionally and nationally of the real situation of Coloradans and especially of women and girls,” she said.

“There is so much distrust of leadership,” Clarke said. “We always wanted to be good citizens, but we’ve been taken for granted. I’m seeing more and more anger and resentment toward our leaders (who are) making draconian rules and don’t have a clue about what’s going on.”

Clarke knows of dozens of small female-led businesses that closed during the pandemic and a half dozen that remained open but still are struggling, she said. Several of the businesses have gone virtual, but many of those owners had to balance taking care of their families with pivoting their businesses, resulting in increased stress, she said. Certain business owners, such as those of restaurants, have the additional expenses of meeting the state’s COVID health and safety guidelines, such as plastic shields and filtration systems, while also hoping they can remain in business, she said.

The business owners and professionals Clarke has talked to also are frustrated at the disparity among states regarding mask mandates and the enforcement of full shutdowns versus allowing businesses to remain open or to take a hybrid approach.

“We see that and we don’t understand why Colorado is open the way it is,” Clarke said.

Clarke normally has “great faith in people,” she said.

“But I’m discovering my faith in government and our politicians, I don’t have any idea what their motivation is,” Clarke said. “I’m quoting from the women I’ve talked to; they said, wow, these people love the power they have. With the swipe of a pen, they create rules for us to follow.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Fort Collins business owner Cindy Skalicky found herself grateful her children are above age 11 and that she didn’t need child care. Yet, like many other female professionals, she had to adjust to the balance of her home and work lives.

“I felt a consistent rub to manage my time better because my kids were home all the time,” said Skalicky, owner of a home-based boutique messaging firm, On Point Communications, about her four children, ages 12, 14, 15 and 17. “I felt this gravitational pull to be increasingly attentive to them because they were here all…