Sports books and textbooks

March Madness betting on Colorado college campuses in the age of legalized gambling

Basketball players at both the University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado State University suited up for games during March Madness last month for the first time in the same year since students in Boulder and Fort Collins — who are over the age of 21, of course — were legally allowed to place wagers on the squads’ NCAA Division I Basketball Tournament games.

The impacts of Colorado’s legalized sports-gambling environment, which saw its first bets placed in 2020 and has proved enticing for fans of all ages, are highlighted for students, parents, school administrators, gambling companies, industry regulators and mental-health professionals during beloved athletics events such as March Madness.

“In our office, we’ve been spending more time focusing on” students’ issues with gambling, said Chris Lord, associate director of alcohol, drug programs and collegiate recovery at the University of Colorado Boulder. “Before the laws changed with sports betting, it’s not that we didn’t talk at all about gambling, but we’ve definitely started doing it more and putting more emphasis on it.”

SPONSORED CONTENT

Before the final buzzer sounds in Monday night’s NCAA Men’s Basketball National Championship game, bettors around the county will have legally wagered upward of $3 billion on March Madness, the American Gaming Association estimates.

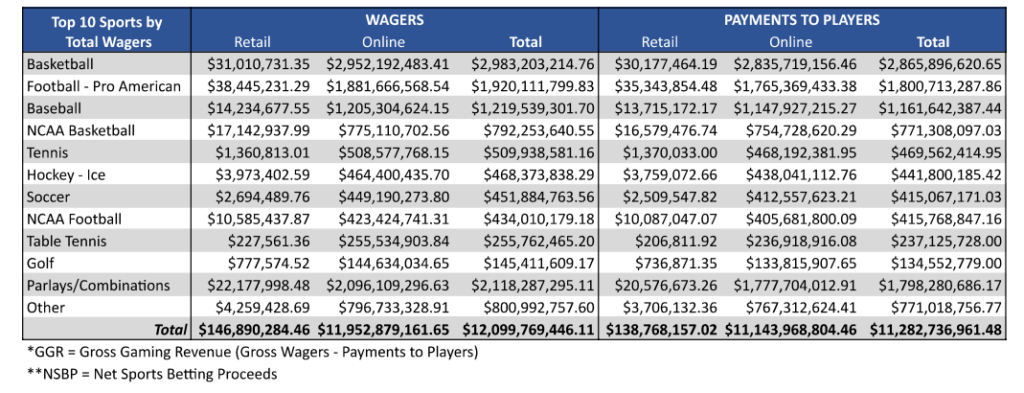

Between May 2020, when legal sports betting went live in the Centennial State, and April 2023, Coloradans had placed nearly $800 million in bets on college basketball, according to the Colorado Department of Revenue, with upticks occurring during major events such as March Madness. Betting on NCAA Basketball accounted for 6.5% of legal wagers placed in Colorado during that three-year period.

On-campus support and recovery outreach and education efforts for college students who may be struggling with gambling issues “really try to focus around those times” when major sporting events such as March Madness are occuring, Lord said. It’s no coincidence that the National Council on Problem Gambling’s annual Problem Gambling Awareness Month takes place in March.

While campus-specific data on gambling trends isn’t widely available, he said, it stands to reason that colleges with teams participating in March Madness would see increased interest in gambling among their students.

The reasons why sports fans gamble are fairly self-evident; a personal stake in the action makes watching games more exciting.

“Gambling in and of itself is not bad. It can be a fun outlet, a social outlet,” said AllHealth Network clinical vice president and licensed professional counselor Sarah Prager, who previously served as the vice president of the Problem Gambling Coalition Of Colorado. “Doing it is not necessarily a bad thing, but we are really focused on awareness that it can be a slippery situation quickly.”

For young gamblers especially, she said, there’s a social-bonding element at play when a group of college students watch games and share action together.

“All of their friends have the (sports betting) app … so they can sit around in a room on the same platform. There’s a lot of peer pressure involved,” Prager said. “Also, all of the marketing is geared toward young people when you’re watching (sports on) TV. The celebrities, the glamorous lifestyle they’re portraying when you gamble, it’s all geared toward young folks who are looking to feel successful and glamorous and fun.”

Colorado bettors need not trek to a casino sportsbook in Blackhawk to place a wager. The only effort required is a couple of quick thumb-swipes across their smartphone screens.

This convenience, experts say, puts online sports betting in a different psychological space than, say, placing a $100 bet on red at a casino roulette wheel.

“A lot of our work right now is helping students realize that sports betting is gambling,” Lord said. “It seems like there is more weight to the word ‘gambling,’ and people tend to see it differently when they do sports betting.”

This psychological-distancing effect can be enhanced by the digital nature of the monetary exchanges on sports-betting apps.

“Anytime you make money less tangible, it becomes easier to gamble,” according to Prager, who said recent studies indicate that as many as one in five college students participate in sports betting. “When your phone is hooked up to your bank account and you don’t hand cash to anyone, it makes it easier to let go of.”

Gambling among college students is often “funded by their student aid,” she said. “That is going to turn into a big problem quicker than an adult (gambler) who has a bigger income.”

Losses on bets placed using student aid money become particularly troublesome because eventually those loans must be paid back with interest, she said. “It’s always compounding.”

While Colorado “saw an absolute increase (in problem gambling) when sports betting was legalized,” that hasn’t necessarily led to a significant increase “in people asking for help,” Prager said.

Ease of access, through gambling apps legalized in Colorado about four years ago or by living in close proximity to race tracks or casinos, generally leads to more participation in betting, she said. “We know that the more people spend on gambling as a population, we’re going to see more people with severe problem-gambling disorders.”

Young people, she said, tend to be particularly susceptible to falling into behavioral patterns that could indicate problem gambling.

“People in their early 20s are still in a period of development where impulsivity is a little bit higher until you hit about 25 years old,” Prager said. “That’s how the brain works. Anything that’s exciting and peer pressure is involved, they’re going to be more susceptible to.”

Younger gamblers are more likely to fall into the trap of “magical thinking,” Prager said, “where they think if they just bet more next time, if they just make a smarter bet next time, they can make up for these losses. … It doesn’t make sense, but our brains start to believe it.”

In theory, sports betting is prohibited for people under the age of 21, a cohort that includes many college students. In practice, assuming that minors on college campuses aren’t placing wagers on games is as naive as assuming they don’t drink beer at parties and bars. “I definitely know of people who are under 21 who do it,” Lord said.

That isn’t to say that sports-betting companies are simply looking the other way when it comes to underage gambling.

“Nobody on any college campus who is under 21 is able to bet on DraftKings. We have a very strict protocol that people have to go through” to prove their identity prior to placing a bet, said a DraftKings spokesperson who spoke to BizWest on background for this story.

The company’s mobile platform is able to monitor transaction and geolocation data for betting trends that could indicate an account is being shared with an unauthorized user.

“DraftKings does not advertise on any college campuses in any way — that’s part of our marketing code of conduct,” the company spokesperson told BizWest.

Notably, this policy also applies to branded information about problem-gambling resources. “We don’t want the DraftKings brand being associated (with betting) on college campuses,” the DraftKings spokesperson said. “If we were to do (problem-gambling) education ourselves, people could say, ‘Well, that’s just a backdoor way of marketing to college kids.’ So we work with other groups and we fund nonprofits that provide education on college campuses. …We don’t want DraftKings (branding) being on a college campus anywhere.”

Despite DraftKings’ policy, other sports-betting companies have identified college students as valuable targets for marketing.

When betting was legalized in Colorado in 2020, gambling operator PointsBet wasted no time in inking a multi-year marketing partnership with affiliates of the University of Colorado’s athletic department, the first deal of its kind at a U.S. college.

The roughly $1.6 million contract was discontinued last year after a New York Times story published in late 2022 that shed light on a controversial referral program baked into the deal that paid CU athletics a $30 bonus every time a new user signed up with a Buffs-specific promo code. PointsBet did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Last year, DraftKings launched a pilot program in Colorado with Kindbridge Behavioral Health, a Tennessee-based mental health-services provider, to help identify problem-gambling behavior among users and direct those in need to free resources for support.

“We want everyone on our platform to engage in responsible play and we are committed to educating consumers on the multitude of resources offered,” DraftKings chief compliance officer Jennifer Aguia said in a March statement.

The partnership, which in March was expanded to all 25 states where DraftKings operates and is mirrored by other gaming companies in the state, arose as a result of Colorado’s Division of Gaming effort to ensure that gaming operators in the state play a more active role in addressing problem gambling.

“This effort underlines our commitment to combat problem gaming with personalized, accessible support,” KindBridge CEO Daniel Umfleet said in a prepared statement last month. “This collaboration sets a new industry benchmark for comprehensive care, ensuring swift and essential support is accessible to those in need.”

Soon after sports betting was legalized in Colorado, “I realized how vastly different gambling addiction, or problem gambling, is to chemical and substance addiction,” Prager said. “The treatment is so different, and it’s so interesting because there are no external (physical or overt behavioral) symptoms, and it’s very easy to hide.”

To be clear, there are signs of gambling addiction — dwindling bank account balance, furtive use of cell phones — “but, currently in our society, nobody links those things” to problem gambling, Prager said. “They automatically say, ‘You’re addicted to your phone’ … or a spouse assumes (the gambler) is cheating on me. …No one assumes gambling.”

The problem-gambling recovery process is “often started by the family of the gambler,” she said. “If you’re a parent of a college student at one of these schools, the first step would be asking very clearly how much they bet on March Madness.”

Problem gamblers are often encouraged to adopt the mantra of “I will not be in action for the rest of my life,” Prager said, even if that means not peeling the McDonald’s Monopoly pieces from a carton of fries. “Anything that involves risk and the potential for a win, a gambler in recovery will not engage in.”

Betting apps have internal systems built into the platforms to identify and combat problematic-gambling behaviors. Users can set wager limits, deposit limits, time-on-site limits, and can even choose to lock themselves out of the apps for a period of time through a process known in the industry as self-exclusion.

“We want this to be for entertainment, and we don’t want you gaming outside of your means,” the DraftKings spokesperson said. “… All of our products, we view as just being for entertainment. If somebody is playing and playing beyond their means, they’re not having fun anymore.”

While sports betting was just legalized a few years ago, the concept is as old as sports themselves. Prior to legalization, the practice was facilitated by black-market bookmakers, who pocketed the proceeds without kicking any revenue to Colorado’s tax coffers.

“States want to legalize sports betting to make sure that they are capturing the revenue that previously went to illegal operators or off-shore companies or bookies or whoever was getting the revenue and not paying any taxes on it,” a DraftKings spokesperson told BizWest.

Colorado has been a pioneer in bringing black-market industries into the mainstream. The Centennial State a decade ago established the nation’s first legalized recreational cannabis market and is poised in the coming years to play a similar role with the psychedelics industry.

The rationale for legalizing smoking a joint, munching a bag of magic mushrooms or placing a wager on the Rams basketball squad often boils down to the same calculus: Colorado adults should be trusted to make responsible choices for themselves, and may opt make those choices regardless of government approval. So why not provide a sanctioned framework for doing so that brings black markets out of the shadows and provides new sources of tax revenue?

“For sites where people play on illegally, there are no consumer protections,” the DraftKings spokesperson said. “There are no repercussions if an illegal sportsbook doesn’t pay you. There are no responsible-gaming tools.”

Basketball players at both the University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado State University suited up for games during March Madness last month for the first time in the same year since students in Boulder and Fort Collins — who are over the age of 21, of course — were legally allowed to place wagers on the squads’ NCAA Division I Basketball Tournament games.