From bucolic to contentious

Colorado River winds 1,400 miles on its path to the sea

NEVER SUMMER RANGE — The pair of moose seemed quite content, grazing on the abundant growth in the meadows of the Never Summer Range near Rocky Mountain National Park, which obviously benefited from the abundant snowpack of 2022-23.

They lifted their heads to gaze at passers by on the Long Draw Road, but quickly returned to their feeding.

Frogs croaked from the lily pads on a pond just off a service road that supports the Grand Ditch. The ditch feeds into the Poudre and then Long Draw Reservoir and ultimately the thirsty northern Front Range.

SPONSORED CONTENT

The area is the headwaters of the Poudre, which flows east. And also the great Colorado River, which flows west.

In fact, the croaking frogs were just a couple of hundred yards from the start of that great western river, a site known to many familiar with the backcountry of the national park but unknown to others.

A pair of young Grand Ditch workers driving on the service road were unaware that the Colorado River’s start was within visual distance, if they knew where to look.

Unlike students in Minnesota, who know where the Mississippi River has its start at Lake Itasca, the origins of the Colorado is not necessarily taught in Colorado. The curriculum guide for teachers makes no specific reference to it, although it does permit its mention under the guidance, “define the problems faced by people of Colorado because of the physical environment…”

But that’s not what this story is about.

It’s about the Colorado River, the river that has defined the growth of the West since covered wagons and later steam railroads carried settlers from east to west, the river that has fed the growth of the population centers and that waters the crops that feed not just the West but much of the nation and world.

It’s about a river that no longer provides enough water to do all that’s expected of it, and that increasingly has become a political powder keg as regions compete for its precious flows.

Not enough flow

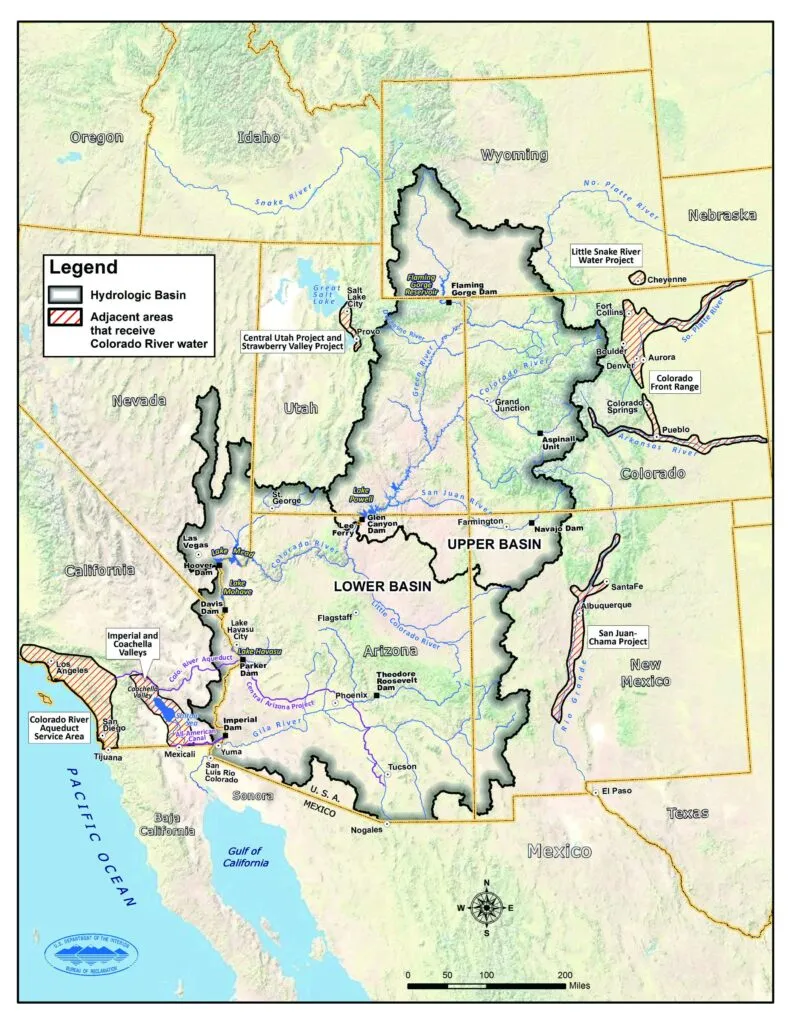

Here’s how the river is supposed to work, according to the grand compromise forged a hundred years ago as the Colorado River Compact.

The river is expected to deliver 14 million acre feet of water each year from snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains, mostly in Colorado. Seven U.S. states share in the flow.

An acre foot

An acre foot is enough water to cover an acre of land one foot deep. 1 acre foot = 325,851 gallons, enough for two or three families for a year.

The upper states of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming are entitled to half the flow or 7.5 million acre feet. The lower basin states of Arizona, Nevada and California get the other half. A 1944 international agreement provides 1.5 million acre feet to Mexico. Twenty-two federally recognized native tribes also claim shares of the river.

The upper basin bases its usage on hydrology, which means that when there’s abundant snow, there’s abundant water the next year. When there’s little snow, there’s less water available and Front Range interests supplement the flow from the multiple small reservoirs maintained by entities such as the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District.

In the lower basin, the situation is different. The region built its economy — agricultural or otherwise — based on the full half share of the river permitted under the compact. The federal government built two massive reservoirs, Lake Powell in Utah and Arizona at 254 square miles in size, and Lake Mead in Nevada and Arizona at 247 square miles. While smaller in terms of surface area, Lake Mead, formed by the creation of one of the wonders of the world, the Hoover Dam, is the largest reservoir in the United States.

In good years, the river provided for usage downstream and abundant snowpack not used upstream helped fill the reservoirs for use in later years. The reservoirs and their dams also provided cheap electricity that also accelerated growth throughout the West.

Diminished flows, climate change, increased demands caused by the 40 million people who depend upon the river all contribute to a growing crisis for those in the path of the river, particularly those in the lower basin where annual usage far exceeds the share anticipated by the Colorado River Compact.

Numbers cited vary, but generally the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation determined that historic flow of the river over 100 years averaged 16.4 million acre feet. In the past 10 years — drought years that are anticipated more frequently in the next decades — consumptive use and loss to evaporation and leaks has averaged 15.3 million acre feet.

The upper basin has consumed 3.5 million to 4.5 million acre feet fairly consistently, according to the Upper Colorado River Commission, and adjusts usage based upon hydrology — basically snowpack. In the lower basin, usage has been 3 million acre feet or more above the 7.5 million acre feet anticipated by the compact. When the river doesn’t provide, the lower basin pulls water from Powell and Mead. The drought impact has resulted in reservoir levels hitting a critical low point where generating electricity at the dams may be in peril.

The issue isn’t new.

In December 2012, the Bureau of Reclamation issued its water supply and demand study, the definitive document that is used as a baseline for discussion. It concluded that the seven basin states, Mexico and tribal nations must immediately begin to address the problem, and the report provided numerous scenarios that could have positive, or negative, impacts.

While discussions have been underway, long-term solutions have eluded all parties. The most that’s been done to reduce consumption has resulted from federal intervention to pay farmers billions to stop farming. Agricultural uses of the river account for 80% of consumption.

The numbers

There’s no shortage of data on the river, thanks to the Bureau of Reclamation and other entities tracking its performance.

Lake Mead was full in 2000 with a surface level of 1,214 feet above sea level but by August 2021 had fallen to 1,067 feet above sea level, or 35% of capacity. As of Aug. 1 this year, it stood at 1,061 feet and held 8.5 million acre feet of water. It has a capacity of 31 million acre feet.

Lake Powell, the second-largest reservoir in the U.S., stood at 33% of capacity in July 2021. In April this year, before this year’s flows into it began, it held 5.26 million acre feet and was at 3,520 feet above sea level. By Aug. 1, it stood at 9.3 million acre feet and 3,580 feet above sea level because of the heavy snowpack this past winter. It has a capacity of 24.3 million acre feet.

The U.S. Geological Survey said in 2020 that the river flow had dropped about 20% over the past century, about half of that due to climate change.

A study published by American Geophysical Union, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, found that the river loses about 8.1% of its flow for every degree Celsius of increase in temperature. Also, the river’s flow decreased by roughly the capacity of Lake Mead during the 2000-2021 drought in the American West.

Whiskey and water

As they say in the West, whiskey is for drinking, and water is for fighting.

The diminution of the river, as might be expected, has pitted the upper and lower basins of the river against one another, although the parties all say publicly that they want a collaborative solution to the problem.

The reason is the imbalanced use of the river with the lower basin, and California in particular, consuming 3 million acre feet or more than what the Colorado River Compact envisioned. Thanks to that usage, California grows much of the produce consumed across the nation as well as the feedstock used to produce cattle and other animal proteins. That agricultural production — and its impact on the nation as a whole — hangs in the background as the states debate water usage, whether acceptable under the compact or not.

Meanwhile, advocates for the upper basin contend that the compact, when written, envisioned a balanced usage, equitable shares of the river, regardless of the amount that the river delivers.

“We’re operating under the letter of the Colorado River Compact,” said Rebecca Mitchell, the Colorado River commissioner from Colorado who is by statute the primary negotiator for the state. “The foundational principle is equity,” she said.

“My focus is on negotiating first the guidelines for Lake Powell and Lake Mead (post 2026), working with tribal nations, working with all Colorado River users and with the federal government,” she told BizWest in an interview.

“Long term, we need to align uses with what’s attainable,” she said.

She said that while it “might be common sense that we can’t live beyond our means, that isn’t necessarily acknowledged everywhere on the river basin.

“There has to be a realization that users below Lake Mead have to come in line with what Mother Nature is providing. Instead of the hammer of the federal government, it’s going to be Mother Nature that determines what each basin can receive,” she said.

The common ground, she postulated, is that “we can live with less. Innovation on the ground is already proving that. The hard ask (for the lower basin) is that you produce the same (amount of crops) with less water. You have to account for evaporation and transit losses.”

California has fought attempts to account for evaporation and leaks in the delivery system, because it stands to lose even a greater share of the river’s water because it’s farther south and affected to a greater degree by warming.

The Center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University estimated that 1.9 million acre feet of water is lost each year to evaporation in the lower basin.

California water users, also, have some of the most senior water rights, which they have been reluctant to compromise.

The fear

The fear by all the states subject to the compact is that they won’t be able to come up with a long-term solution.

After prodding, the upper basin developed a five-point plan to develop plans for conservation of the river’s water and assist with refilling Powell. The lower basin put forward a plan to reduce usage by 3 million acre feet by 2026 and 1.5 million acre feet by 2024, short of the 2 million to 4 million acre feet that had been requested as an immediate reduction.

If long-term agreements can’t be reached among the states, the “hammer of the federal government,” as Mitchell called them, could come into play.

Sen. Michael Bennet, senior senator from Colorado, said “there’s always a risk” if the states fail to come up with a plan of their own. “If we can’t get to an agreement, that’s an unfortunate harbinger of what 2026 will look like,” he said, in reference to discussions to get beyond short-term fixes and get to more or less permanent reductions in water use after 2026.

Bennet, and his Senate counterpart John Hickenlooper, are working to form alliances with senators from other states and to communicate the issues, which aren’t necessarily apparent outside of the river basin.

“It’s vital for us that the other states understand what it’s like living through a 1,200-year drought. A lot of states don’t (understand),” Bennet told BizWest.

“When smoke from California fires showed up in New York for the first time, it was revealing. People realized that we had to do something different,” he said. Still, he understands that a compromise between the states is critical to avoid “having an unwelcome solution crammed down on us by the Department of Interior.”

Bennet understands that federal investment in the region is critical to finding permanent solutions. “John Hickenlooper and I are raising this every single day,” he said.

Some of that investment will come in the federal Farm Bill — investments in soil conservation “unlike anything we’ve seen since the Dust Bowl.

“For the first time, there’s acknowledgement that the 40 million people who live in the basin of the Colorado River, they’re worthy of that kind of investment on behalf of the U.S. taxpayer,” Bennet said.

Potential investments

The estimate of costs of investments might be considered mushy. The 2012 Bureau of Reclamation report, now more than a decade old, made projections that included multiple scenarios. Even the “slow growth” scenario projected consumptive uses to require 18.1 million acre feet by 2060. Population under the slow growth projection would rise to 49.3 million by 2060, up from the 40 million people now in the river basin.

While conservation, limiting evaporation, plugging leaks and other strategies attempt to get at uses, potential strategies also include increasing supply.

Some like cloud seeding come with a modest cost and questionable efficacy. Others, such as bringing in other sources of water from other regions, are much more expensive. They include bringing water to the Front Range from the Great Lakes, dragging icebergs to southern California, building submarine pipelines, and floating massive water bags of freshwater from the Columbia River down the coast to southern California.

All options and all categories could yield 5.7 million acre feet by 2035 and maybe 11 million acre feet by 2060, according to the bureau’s report.

Some of these solutions would require decades to accomplish, if the political will and dollars can be found. Icebergs, for example, would cost upward of $3,400 per acre foot to accomplish. Importing Great Lakes water to the Front Range would cost $2,300 per acre foot, the report said, in 2012 dollars.

Recent events

While the massive snowfall in the Rocky Mountains this past winter gave the river and its reservoirs a brief reprieve, no one is expecting those conditions to continue. Droughts lasting five or more years are projected to occur 50% of the time over the next 50 years, according to the Bureau of Reclamation 2012 report.

“It’s important not to lose the time that nature has given us,” Mitchell said. “We have to sit at the table and talk about what we can do. What ideas do we have (among the states) so this is not managed for us. … It’s not going to be just one thing that saves us. (Federal money) needs to be spent for permanent reductions in use.”

Because the lower basin has come up with some reductions, negotiators are focusing on the post 2026 plan to control the reservoir levels and find ways to permanently reduce usage, even as the population grows and the climate warms.

Mitchell said her focus is on defending the compact, making sure interests of tribal nations are considered, and changing the mindset about releases from Powell so it is managed by hydrology instead of by the declining levels of Mead.

NEVER SUMMER RANGE — The pair of moose seemed quite content, grazing on the abundant growth in the meadows of the Never Summer Range near Rocky Mountain National Park, which obviously benefited from the abundant snowpack of 2022-23.

They lifted their heads to gaze at passers by on the Long Draw Road, but quickly returned to their feeding.

Frogs croaked from the lily pads on a pond just off a service road that supports the Grand Ditch. The ditch feeds into the Poudre and then Long Draw Reservoir and ultimately the thirsty northern Front Range.

The area is the headwaters of the Poudre,…