SuviCa uses undergrads to test cancer drug on the fly

Rack one up for the fruit flies — and the concept of involving undergrads in front-line research, as well.

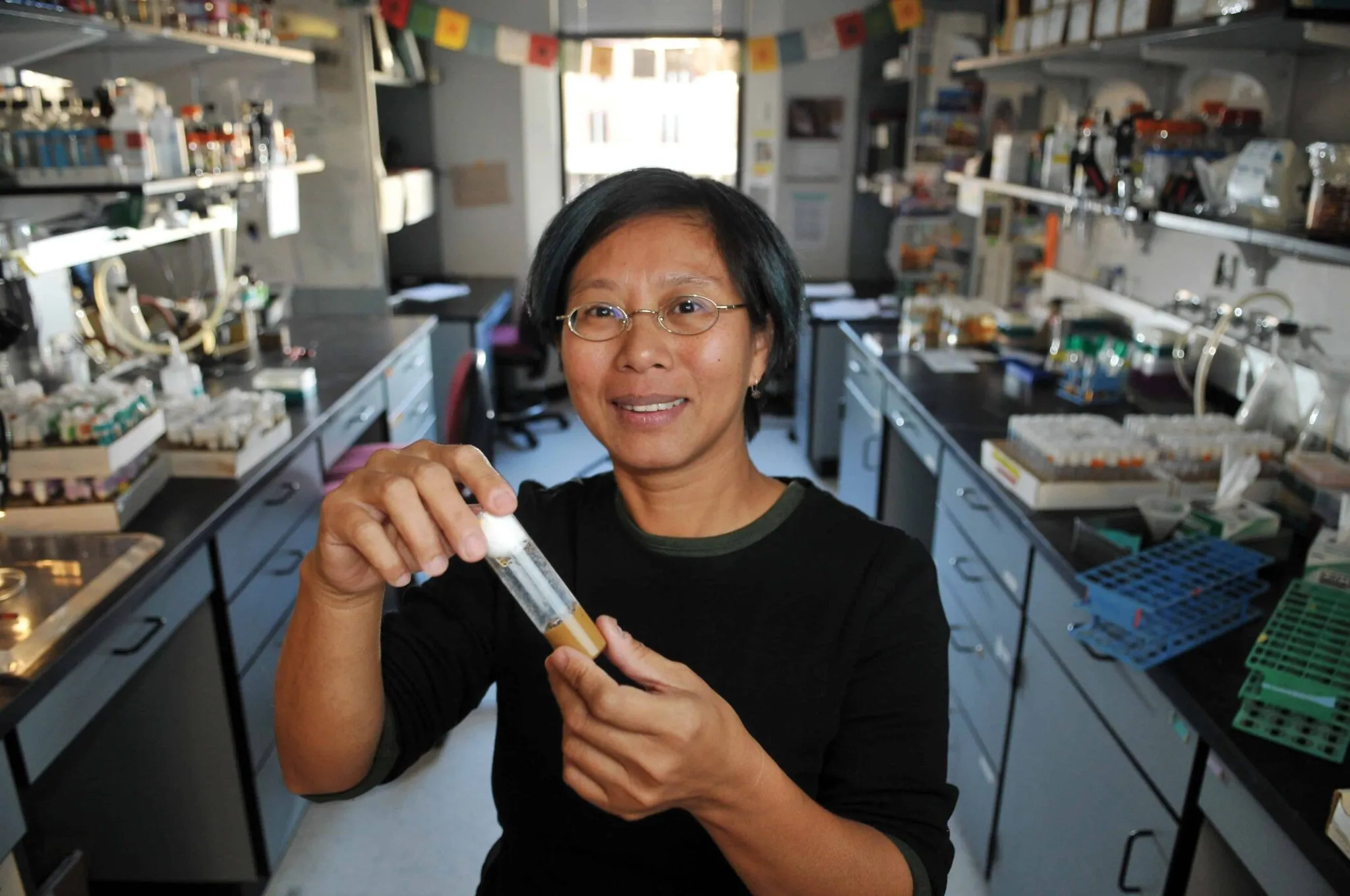

Both the flies and the students who work with them were instrumental in bringing Boulder biotechnology company SuviCa Inc. roughly $1.5 million in federal funding to develop a treatment for head and neck cancer last fall. The University of Colorado Boulder technology transfer company, headed by Tin Tin Su, its chief science officer and a CU professor, has a drug candidate known now as SVC112 that helps prevent regrowth of cancerous cells following radiation therapy.

While at…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!