Water Wars: Will more storage meet growth’s demands? Will less storage limit it?

The 1989 baseball movie “Field of Dreams” is best known for originating the familiar catchphrase, “If you build it, they will come.”

But along the booming but semi-arid northern Front Range, if reservoirs aren’t built to store mountain snowmelt and water becomes too expensive, will they still come?

“We are in the thick of that debate,” said Reagan Waskom, director of the Colorado Water Institute at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. “In a sense, water becomes a proxy war for growth management.”

SPONSORED CONTENT

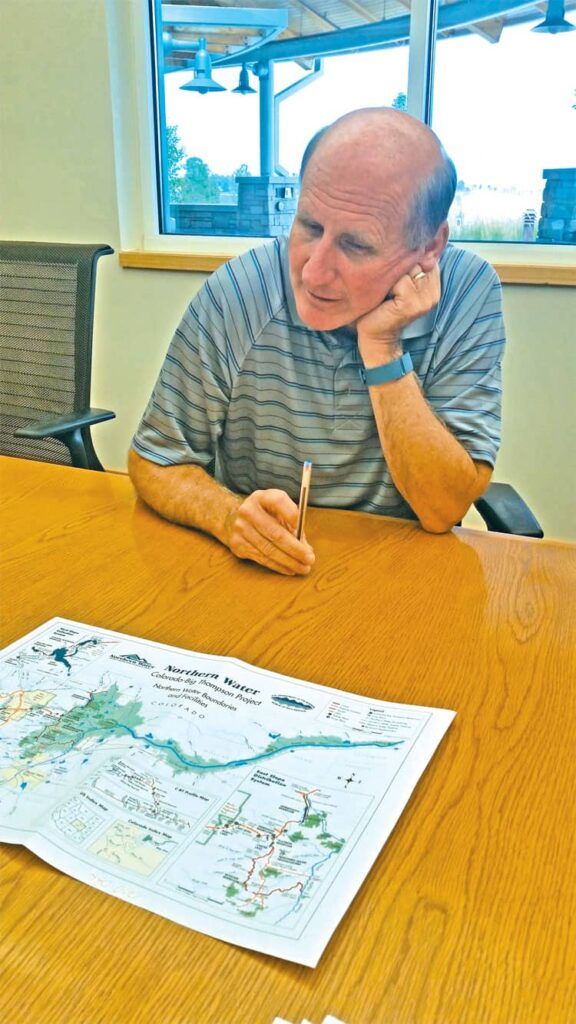

Municipalities, developers and agriculture interests are trying to figure out how to provide enough water to supply a population expected to double in the next few decades. If more water-storage reservoirs are built, the new residents and businesses will come, said Eric Wilkinson, general manager of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, known locally as Northern Water, “but if we don’t build it, they’re still going to come anyway.

“Controlling growth by limiting water? Possibly if you’re living on the moon.”

New housing affected

Not that the rising cost of water hasn’t stalled the inevitable, said developer Landon Hoover, president of Timnath-based Hartford Homes.

“It’s delayed some developments. We are limited in the number that we can do because of the magnitude of the water cost. It just stretches resources,” Hoover said. “Generally speaking, water is now more than the raw land cost. Five or 10 years ago, water was around $6,000 a house. Now it’s anywhere from $22,500 to $30,000.”

The prices delayed the start of two Hartford projects near Timberline Road and East Vine Drive in Fort Collins, he said.

Opinion

NISP the right answer for area’s future

NISP and its SDEIS: 2015’s summer disaster movie

Fort Collins is served by three large water-delivery systems: the city utility, which was started more than a century ago and owns senior water rights purchased when water was cheaper, and two water districts formed in the 1950s that own more-expensive junior rights. Where a new development is located determines what a developer must pay for water.

To start his housing developments, Hoover said, “I have to find the water shares, buy them upfront and then dedicate them to ELCO (the East Larimer County Water District). It ends up doubling the cost of the land, and so it takes a lot more resources to finance the development and limits the development.”

The costs are passed along to homebuyers, he said.

Even so, “it’s absurd to think the supply of water is going to keep people from wanting to be here,” Hoover said. “Oh, sure, at some point, if the traffic is so bad, people wouldn’t want to live here anymore — or if the cost of living gets so expensive. But both of those have to get so extremely bad before it would inhibit growth.

“Just making water too expensive? That’s not a strategy for dealing with growth. People still want to live in Boulder even though housing costs are through the roof.”

Northern Water spokesman Brian Werner said developers are “going to find the water. It’s doubled in price but still cheap. People will still want to live in Northern Colorado. It’s the economic driver of willing buyer, willing seller.”

Wilkinson agreed. “Most people don’t even look at the water piece of their new home,” he said. “Unless we get it up to 50 percent of a home’s value, it’s not going to affect it.”

The area served by Northern Water has a population of 880,000 people, Werner said, but the state demographer expects that to grow to as many as 1.5 million by 2050.

“Seven of the 10 fastest-growing cities in Colorado are in Northern’s boundaries,” he said. “We can’t ignore it.”

The growth is coming, Hoover agreed. “To not prepare for that is unwise.”

NISP to the rescue?

Northern Water wants to prepare for that growth by building the Northern Integrated Supply Project. If approved, NISP would include construction of a pair of reservoirs that, combined, could store more than 215,000 acre-feet of water, 40,000 of which would be allocated to municipal water supplies annually.

Glade Reservoir, which would be larger than Horsetooth Reservoir west of Fort Collins, would be built north of the intersection of U.S. Highway 287 and Colorado Highway 14 northwest of Fort Collins and would hold up to 170,000 acre-feet of water diverted from the Cache la Poudre River. Galeton Reservoir would be built east of Ault and Eaton in Weld County and hold up to 45,000 acre-feet of South Platte River water.

About a dozen cities and towns and four water districts have signed up to buy water from the NISP project if it wins final approval from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Supporters, including the Colorado Association of Commerce and Industry, the Northern Colorado Legislative Alliance and many other business- and agriculture-backed groups, see the project as crucial to keeping up with the growing demands of development, industry and agriculture along the Front Range.

Opponents have said the project would drain water from the Poudre as it flows through Fort Collins, limiting opportunities for recreation, including tubing, whitewater kayaking and fishing.

Gary Wockner, director of Save the Poudre, the group spearheading opposition to the project, said he isn’t sure whether growth would still come if NISP isn’t built — “Our organization has not engaged in the growth debate. We’re trying to save the river” – but he thinks it’s a dangerous gamble.

“NISP is proposed to be paid for by revenue bonds, which will be offered by all 15 of the stakeholders,” he said. “They’ll have to borrow money, and then hope growth comes to pay the bonds back. If the growth does not come, they’ll have to charge their current customers much higher water rates. Some communities are already doing that.

“Building NISP will actually subsidize growth and force small towns to grow — market themselves as fast as possible — or potentially default on their bonds.”

Impacts assessed

The cities of Fort Collins and Greeley and the Environmental Protection Agency have issued reports critical of the Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement issued by the Corps in June, citing incomplete or even flawed data on issues including water quality and temperature. Moreover, Greeley officials have said reduced flows in the Poudre would force that city to spend more on water treatment.

“It would be a large one-time capital expenditure — we can only estimate tens of millions, plus additional ongoing maintenance and operations costs,” said Eric Reckentine, Greeley’s deputy director of water resources. “If you’re reducing flows in the river, you’re decreasing water quality. Less water in the river, but the same sediment load. Sediment and nutrient load increases, which decreases water quality.”

For Northern Water officials, however, the litany of complaints are just part of the process that will shape the Corps’ final environmental impact statement, expected by early next year.

“It’s always been our understanding that the Corps basically planned the process in this way — data from Phase 1 to be used in Phase 2,” Wilkinson said. “It will be developed and analyzed prior to the FEIS.” Until then, he added, “I’ve been told I have alligator skin.”

Criticism of the SDEIS is “being blown way out of proportion,” Werner added. “It’s making something out of the process that obviously isn’t intended in the process.”

Wilkinson said he’s unfazed by the Fort Collins City Council’s unanimous resolution of opposition to NISP as outlined so far in the SDEIS.

“You could categorize that as possibly conditional opposition,” he said. “I don’t read in their resolution that they cannot support NISP in its current configuration. If their concerns can either be answered or somehow otherwise addressed, there’s room there to talk. They may never support it, but what they’re saying is they can’t support it now. We’re going to talk to Fort Collins and say, ‘Let us understand your concerns.’

“There appears to be a difference in analysis between Corps consultants and Fort Collins’ and Greeley’s consultants,” Wilkinson said, “but obviously, that’s what the public comment period is for. There’s going to be a technical analysis. That’s part of the NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act of 1970) process — to sift through those facts.”

“We need the storage to be able to capture that water in wet years instead of feeding the Mississippi River,” said Dale Trowbridge, general manager of the Lucerne-based Cache la Poudre Reservoir Co. and New Cache la Poudre Irrigating Co.

But what happens if NISP isn’t built — besides the copious amounts of Colorado-owned water that would be lost to Nebraska and points east?

Wockner sees conservation, efficient use and growth controls as some of the answers. But conservation is another issue that Northern Water and Greeley see differently.

Greeley has had an “odd-even” system for outside watering based on the last numeral of a street address, Reckentine said. “We’ve had it since 1907. We’re the only city in Northern Colorado that has water restrictions all year long. When other cities go into drought restrictions, they’re basically into our standard.

“The fathers of Greeley understood water rights very well,” he said. “We’re known as Tree City USA, and it certainly doesn’t affect lawns. You don’t need to water every day to do that.”

However, Werner noted that other Colorado cities dropped odd-even restrictions years ago. “Communities tended to use more water because people watered more on their day,” he said.

‘Buy and dry’

The other option to provide for growth, both Wockner and Wilkinson said, is to buy water rights from farmers and ranchers.

“Eighty percent of the water is still being used for agriculture, so they’re going to buy it off of ag,” Werner said.

But agribusiness is of two minds, Waskom said. “People in ag want to see the industry stay profitable and strong, but each farmer and rancher wants to preserve the right to sell to the highest bidder. It’s a personality split.”

On one side are people such as Larry Patterson, a lifelong rancher who raised cattle and sheep in Wyoming and the Western Slope and who now grazes 13 horses on 35 acres near Wellington and nine more on 12 acres southwest of Fort Collins.

“They’ve got to hold onto their water rights,” he said. “I don’t think they know what they’re doing. It’s pretty hard to get water if you don’t have a decent right.”

Related

Thornton a major player in NoCo water

But others are more than willing to sell their rights — not only to municipalities but to developers such as Hoover at Hartford Homes.

“We’ve made it such a focus of ours to go find that water — door to door,” Hoover said. “Farmers, ranchers, exclusively. A lot of times they’re cashing out, putting it into another business they have. Most are drying up, and selling it for development.”

When Waskom talks to water-utility managers, he said, “they tell me they have buyers coming to them on a regular basis, willing to sell water.”

“The farm economy, age of farmers, land prices — that all enters into the equation,” Werner added.

The biggest buyers are municipalities, Trowbridge said. “The cities have the capability with their population, to increase the price they pay, so it’ll continue to drain water from agriculture.”

But is surrendering agricultural land either to development or to dryland farming — the phenomenon known as “buy and dry” — desirable?

“Some of the land is in flux between ag and dry, and some has been dried up altogether,” Trowbridge said. “They don’t want deep-rooted crops. A lot are just put into grass, and it’s not even that good for grazing.”

Nearer cities and towns, the dry land is more likely to sprout houses.

Wilkinson frames preserving agriculture, such a major part of Colorado’s economy and culture, as a selling point for NISP.

“Do you want to have an ag economy that’s extremely important to Colorado’s environment, its economic vitality? Do you want locally grown food? The average farmer feeds an average of 200 people,” he said.

Trowbridge said his companies’ system is one of the entities involved with NISP. “We’ll exchange water with Northern’s system,” he said, but added that agriculture is a key to making some of the proposed NISP agreements work.

“The NISP project is to divert water from the Poudre into Glade. Some of that is our water,” he said. “So in order to make that up to us, they’ll have to draw water out of the South Platte into Galeton. In order to make the exchange, we still need to irrigate. There has to be ag use here.”

Alternatives studied

Waskom outlined some possible alternatives to buy-and-dry, including “forbearance” agreements and fallowing arrangements.

“A farmer agrees not to plant a crop, and the water they’d use to irrigate they’d transfer to another use on a short-term basis,” he said. “Water law allows that to happen three years out of 10. It’s a business deal. The farmer plays golf and gets a check from the city. The limitation is that a farmer can’t walk away from his markets and labor and expect they’ll be there next year.

“My institute has been very involved in doing research around those agreements,” Waskom said. “We believe there is potential there. That said, municipal water managers want to own their portfolios. They would rather lease to ag than have ag lease to them.

“Our current water court structure makes it difficult and expensive. Is it a pathway for the future? Yeah. Does it abrogate the need for Glade now? Probably not.”

The reason, Waskom said, is drought.

“Water resource managers are always planning for drought,” he said. “Drought is what keeps them awake at night. It looks like we’re building more than what we need, but there will be drought in the future. We just don’t know when.

“The one thing the climatologists tell me they’re pretty certain about — temperature increases. We have frequent drought anyway on the Front Range, but hotter droughts are always more serious than cooler droughts. With the wildfires in 2012, cities had their water resources compromised.

“We don’t know what precipitation is going to do, but climatological records already show increasing temperatures in Colorado. That’s a trend we’re going to stay on, and that concerns water managers.”

Explaining climate change can get political, Waskom said. “We’ve been talking to extension agents, and there’s lots of resistance based on values. It’s fascinating how the science of climate change is inconvenient, but the science of GMOs is inconvenient at the other end of the spectrum.”

Politics and the western spirit of independence also have played into state and local governments’ resistance to linking land-use planning to water, he said.

Another idea the institute is studying is underground water storage.

“In this area, we get three feet of evaporation off the top per year” from an impoundment such as Horsetooth or Carter Lake southwest of Loveland, Waskom said. “Storing water underground in aquifers tends to be nonevaporative. It is feasible, but there’s scientific debate about it, and policy limitations too. Could underground storage decrease the need for NISP? There’s scientific debate about that. Because of the unknowns in the science and the energy costs of recovering that water, though, it wasn’t deemed a viable alternative to Glade Reservoir. Could it be in the future? I think so.”

The bottom line

Meanwhile, the growth debate continues.

According to Wockner, “NISP is a drop in the bucket of all the new growth they’re projecting will come.” But Trowbridge said he believes building NISP will take at least some of the pressure off.

“Go back 70 years,” he said. “If they hadn’t built Horsetooth or Windy Gap, Colorado wouldn’t be the vibrant economy it is. Our water comes in the form of snow. You have to take advantage of what you get. The last few years, we’ve seen a lot of hit to our economy for lack of storage.”

“I doubt most developers know enough about NISP to judge whether the tactical implementation of it is good or bad,” Hoover said. “But developers see that there needs to be a solution for water storage in Northern Colorado if people want affordable housing, places where teachers, firefighters, middle-income families can live, $300,000, $400,000 houses.

“There’s really a limited supply of water, and we’re nearing the end of that supply. Unless demand shuts off, there’s no relief for prices. The issue isn’t whether we have enough water rights, the issue is we don’t have enough storage. By having storage, it will at least temper water prices. I don’t know if it’ll ever drastically lower them.”

The bottom line, Waskom said, is that “we’re going to need reservoirs, infrastructure, conservation, underground storage, ag deals, all of the above, to keep Colorado’s economy strong and vibrant into the future.”

Dallas Heltzell can be reached at 970-232-3149, 303-630-1962 or dheltzell@bizwestmedia.com. Follow him on Twitter at @DallasHeltzell.

The 1989 baseball movie “Field of Dreams” is best known for originating the familiar catchphrase, “If you build it, they will come.”

But along the booming but semi-arid northern Front Range, if reservoirs aren’t built to store mountain snowmelt and water becomes too expensive, will they still come?

“We are in the thick of that debate,” said Reagan Waskom, director of the Colorado Water Institute at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. “In a sense, water becomes a proxy war for growth management.”

Municipalities, developers and agriculture interests are trying to figure out how to…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!