Colorado River crisis: Operating on ‘water time’ no longer an option

Decisions by the U.S. Department of the Interior and its Bureau of Reclamation to slash water releases in the lower basin states from Lake Mead and Lake Powell on the Colorado River should serve as a wakeup call.

Reductions are coming to Northern Colorado, too.

Tuesday, after Monday’s deadline when the seven western states in the Colorado River system were supposed to put forward a plan to reduce water use, the federal government issued a statement and a directive that water-conservation measures outlined in a 2019 drought contingency plan would be implemented.

SPONSORED CONTENT

How Platte River Power Authority is accelerating its energy transition

Platte River Power Authority, the community-owned wholesale electricity provider for Northern Colorado, has a history of bold initiatives.

Based upon levels in the nation’s largest reservoirs, Arizona will see a 21% reduction, or 592,000 acre feet, in water made available to the state from the system. Nevada will see a 25,000 acre-foot reduction or 8%, Mexico will see a 7% reduction or 104,000 acre feet, and California will see no reduction unless the lake levels fall even further than predicted.

The reductions fall far short of what the federal government said earlier would be necessary: 2 million to 4 million acre feet of reduced usage throughout the system.

The reductions are necessary to protect the nation’s investment in the reservoirs and the power plants that fuel much of the west.

The Bureau of Reclamation projects that Lake Powell will drop by January to a surface elevation of 3,521 feet or 32 feet above the minimum power pool. Lake Mead’s elevation will be 1,047 feet.

“There are implications for Northern Colorado and the state generally,” said James Eklund, an attorney with Sherman and Howard and the former Colorado commissioner to the Upper Colorado River Commission.

“The news yesterday was a signal. They [the federal government] tried to get the states to come up with a plan. The states failed. People thought the federal government would come up with a plan, but it refrained.”

“It means more uncertainty. The region [Northern Colorado] depends on thousands of acre feet of Colorado River water; it should serve as a call to action,” Eklund said.

While the upper basin states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico did put forward a five-point plan, Eklund said it didn’t go far enough and didn’t include hard targets for reductions in water use in the upper basin. “The state has pointed a finger and placed blame [on the lower basin]. It should have come up with a plan by the deadline. … they didn’t hand in the homework assignment.”

“Every day without a plan results in uncertainty. Seventy percent of the flow of the Colorado begins in our state.”

Jennifer Gimbel, senior water policy scholar at the Colorado Water Center at Colorado State University, agreed that the federal actions Tuesday didn’t go far enough. “We thought we’d find out yesterday what the government is likely to do,” she said.

Actions yesterday mean “it’s business as usual for Northern Colorado” but residents should be more aware of the “impending crisis.”

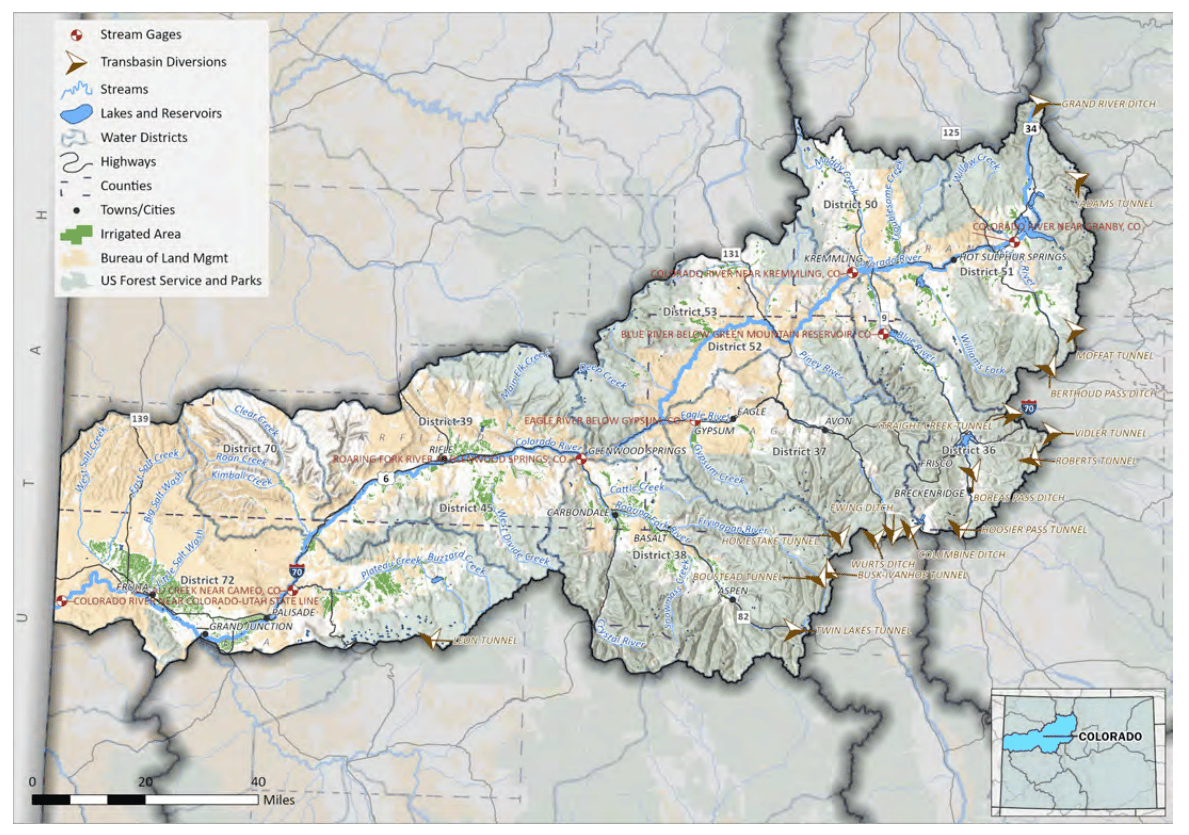

Cities and farms getting water from the Colorado Big Thompson Project and Windy Gap should be aware that supplies could be curtailed in future years.

“We should be prepared to conserve more and reduce usage,” she said.

Adam Jokerst, former city of Greeley deputy director of water resources and now Rocky Mountain regional director of WestWater Research in Fort Collins, said it is time to take action, and he sees the $4 billion committed in the federal Inflation Reduction Act as a means to implement some conservation measures in the West.

Eklund, who signed off on the 2019 drought contingency plan that was supposed to prevent shortfalls through 2026, acknowledged that the plan has come up short and solutions will require “big and ambitious projects. … We’ll have to spend a lot of money to assure access to water.”

Eklund expects that water entities will need to look closer at aquifer projects and native supplies. “We need to develop our native supplies, and fast. Not in ‘water time,’ which can take decades but we need to run our two-minute offense.”

Decisions by the U.S. Department of the Interior and its Bureau of Reclamation to slash water releases in the lower basin states from Lake Mead and Lake Powell on the Colorado River should serve as a wakeup call.

Reductions are coming to Northern Colorado, too.

Tuesday, after Monday’s deadline when the seven western states in the Colorado River system were supposed to put forward a plan to reduce water use, the federal government issued a statement and a directive that water-conservation measures outlined in a 2019 drought contingency plan would be implemented.

Based upon levels in the nation’s largest reservoirs, Arizona will see…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!