Boulder, big and small: Growing high-tech giants create chances, challenges for startups

BOULDER — They all want to be here. But how can they all fit in?

Boulder draws some of the nation’s most dynamic and successful companies, thanks to its quality of life and its concentration of capital — both human and monetary. While technology giants such as Google, Amazon and Twitter continue to expand, the lure of daring venture capitalists and a wealth of resources draws budding entrepreneurs hoping to change their part of the world.

But how well can the big players and the new kids on the block coexist? With commercial space finite, affordable housing scarce and the ability to offer competitive benefits limited at least at first, startups in the shadow of the giants sometimes find it challenging to secure a place in the sun.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Empowering communities

Rocky Mountain Health Plans (RMHP), part of the UnitedHealthcare family, has pledged its commitment to uplift these communities through substantial investments in organizations addressing the distinct needs of our communities.

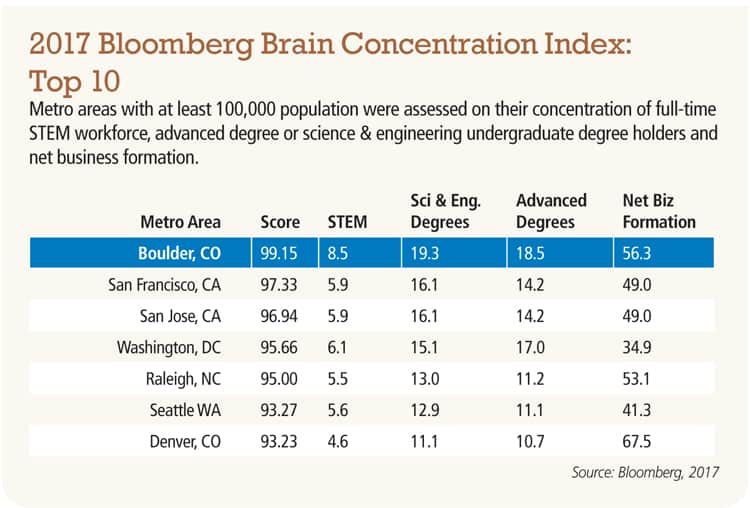

But they also find that Boulder’s tide of synergy tends to lift big and small boats alike. The result is that the quirky city at the base of the Flatirons boasts the nation’s most highly educated workforce and its most robust concentration of employment and employees within manufacturing- and STEM-related jobs.

Statistics for the second quarter of 2019 showed that Boulder-based startups raised $215 million in venture capital, more than half of the entire state of Colorado’s total of $400 million.

Making that synergy work didn’t just happen, though.

“For so long,” recalled Boulder Chamber president John Tayer, “we were a community that had only a few pillar primary businesses in our town — IBM, Corden Pharma, maybe Ball. What we were seeing is entrepreneurship and innovation, and that resulted in us being designated the startup capital of the nation. It was a tribute to risk taking and entrepreneurial spirit.

“What we often found challenging as these startups grew and started to need support, though, is that they ended up not being able to find the resources they needed in Boulder and ended up gravitating to the coasts. The tradeoff for moving their operations out of our community was that we were often able to fill the empty void with initial startup activity.

“That’s not healthy. You need a diversity of businesses through their growth cycles to make sure the economy is well balanced.”

Starting about 15 years ago, however, “startups started getting purchased by larger companies,” Tayer said. “Rather than locating, they said, ‘We see a lot of dynamism in this ecosystem and want to be a part of it.’ They started taking root here. They said, ‘We’re gonna plant here and start to connect with the entrepreneurial environment.’ They wanted to partner with other companies that they could absorb, but also the overall environment or creativity and risk taking they know is vital to their own success.

“The benefit is that we have a broader diversity of businesses in their development cycle,” he said. “So as the economy shifts and there’s not a lot of venture capital, we’ll be thankful we have the more stable companies like Google and IBM. We’re looking to always balance and stabilize our economy. It benefits the Boulder workforce, its residents, makes our community stable and maintains our high quality of life. We see this evolution of the economy as a positive for our community and something we should be celebrating.”

The startup-friendly climate led to the founding of seed accelerator Techstars in 2006. Natty Zola, managing director for the Techstars programs in Boulder, has managed its last five cohorts and cited some other advantages to Boulder as well.

“If you leave a big company here and start a startup, there are more potential acquirers here,” he said, “and if you start a startup that doesn’t work, it’s a place where you can have a soft landing between startups. You don’t have to move out of the area and do good work before you start another one. Maybe you can take your job back at Google or Facebook for a while until you start your next one; that’s actually a big benefit.”

“That’s all part of the magic that makes Boulder special,” added Clif Harald, executive director of the chamber’s economic-development arm, the Boulder Economic Council. “We have a very powerful ecosystem that supports large and small alike.”

Brad Feld, co-founder of the Foundry Group, began financing technology startups in the area in the early 1990s.

“If you look at the evolutionary history of Boulder,” Feld said, “the presence and growth of companies like Google have tracked with the regular and steady growth of the overall startup community.”

Feld always “talks about how important large companies are to the vitality of smaller startups,” Harald noted, “because big companies will partner with startups — funding, contractual services. Large companies’ employees can be mentors to startup entrepreneurs. Or they’ll spin off new companies. That interdependence of larger and smaller early-stage companies is a powerful, almost mystical kind of synergy.

“And remember, not all large companies are as good at innovation as startups or have the nimbleness and agility that can jumpstart success.”

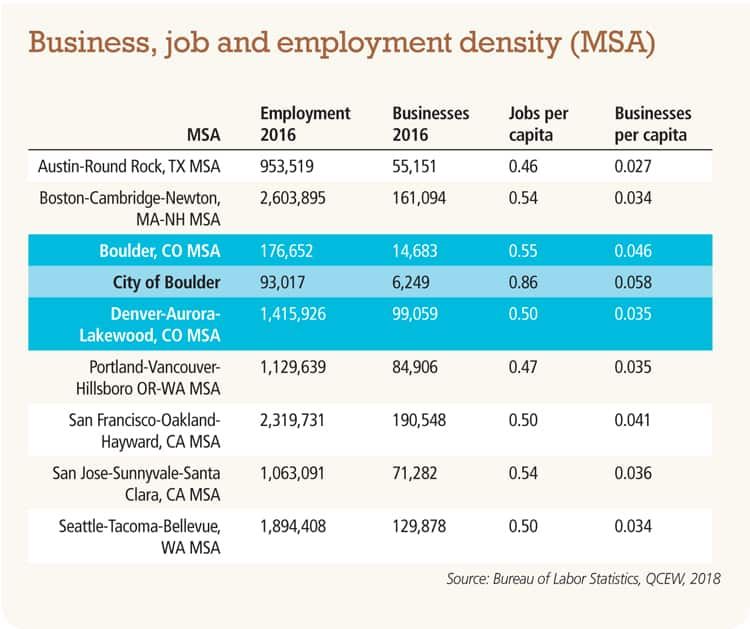

As visible as are some of Big Tech’s expanding footprints, such as Google’s massive facility along 30th Street, Harald is quick to point out that Boulder remains mostly a small-business economy. He said data provided by the University of Colorado Boulder indicates that 98 percent of businesses in the city have 50 or fewer employees and 76 percent have fewer than 10.

Are startups at a disadvantage when it comes to competing for talent and space as well as finding affordable places for workers with smaller paychecks to live? Tayer, Harald and Zola don’t think so — at least not now.

“You can’t make the assumption that individuals who have tech experience always want to gravitate to the biggest player in the field,” Tayer said. “A lot of them are energized by entering a startup business; they have the opportunity to grow or develop themselves. It’s not a straight question of salary and benefits. Many folks looking for career opportunities that are fulfilling find it in a fresh-off-the-ground startup.”

Zola said many workers attracted to Boulder are “willing to sacrifice some near-term benefits for the opportunity to be part of a startup. Not everyone can forgo a standard level of benefits, but how about the learning curve? Big companies can’t offer that experience. Sure, perks or benefits are flashy and nice, but the benefits at a startup are a small team, an agile environment, more autonomy.

“You can go somewhere and earn fancy salaries at the big players, but your opportunities are limited in terms of equity acquisition. There’s a lot more value being put on meaningful amounts of equity in an early-stage company in Colorado.”

Availability of office and industrial space also has benefitted from the synergy, Tayer said.

“In many respects, big tech has been the catalyst for new commercial development,” he said. “We’ve not seen a diminution of available space for startups. Some of our larger tech industries have built their own accommodations and then rent out space, so they’re often a catalyst for further entrepreneurship and innovation. We also get a number of new-business inquiries interested in locating near some of the larger tech companies.”

The inevitable downside, he noted, is that “our strong economy drives up housing prices. We cannot deny we are in a very desirable place to live.”

Boulder’s expansive and scenic parcels of designated open space enhance that quality of life, but also impose limits on areas that can be developed for housing.

“We’re a huge supporter and protector of open space,” Tayer said. “It’s not only a quality-of-life asset but a significant driver of our economic success. We also recognize that within the doughnut of open space, there’s a great opportunity for more compact developments and more multi-use development in a variety of areas around our community — more diversity of housing stock.”

He cited the work of the chamber’s Boulder Together program to develop that broader spectrum of housing diversity, “while also recognizing that not all our workforce is going to want to work here or we can necessarily accommodate. Part of that is improving our transit system to move commuters in and out.”

Harald agreed that “the Denver-Boulder housing market can be expensive for people, but it’s not as expensive as coastal communities. Housing affordability is relative. We’ve seen kind of a balancing in the housing market, a little tempering of significant appreciation in prices. And we’re starting to see wages going up. So we might see more of an equilibrium between housing prices and incomes.”

Zola said Techstars clients haven’t had much trouble finding office space, either landing in co-working situations or subleased offices.

“When the company’s scaling, we have more challenges because there are fewer large office spaces. We’re still pretty cost-effective compared with the coasts, though.”

“When the company’s scaling, we have more challenges because there are fewer large office spaces. We’re still pretty cost-effective compared with the coasts, though.”

The hefty cost of housing is “probably the bigger issue,” Zola said. “Your savings last a shorter time to do a startup. That’s probably the more concerning thing to me. Maybe you offer discounted salaries in the beginning, but how long can you go before revenue is enough to pay for it or you need to raise money? That’s not stopping them but it’s in the back of their minds.

“Making sure your employees can live comfortably is more of a macro concern for me.”

Boulder’s city government has wrestled with the affordable-housing issue for years, and in recent months has been debating a proposal that has left Boulder Chamber officials and commercial real-estate firms less than comfortable.

In February, Boulder leaders implemented a development moratorium as a way to address concerns that investors in the city’s Opportunity Zone — a 2.5-square-mile tract bounded by 28th and 29th streets, Arapahoe Avenue and the Diagonal Highway — would reap all the rewards of the program and speed up gentrification rather than assist disadvantaged home seekers. Local affordable-housing advocates and some City Council members warned that without changes to the city’s land-use table, the city’s balance between jobs and housing would be made worse by commercial development in the zone.

The federal opportunity-zone program, created in 2017, lets capital-gains taxes be deferred if the gains are used for real-estate investments. It also defers future appreciation, so that if the capital-gains investments are left in place longer than 10 years, taxation is excluded completely.

“On a macro level, we understand council’s position on growth, and it’s not a new thing to Boulder,” said Becky Callan Gamble, president of Dean Callan & Co., a commercial real-estate firm operating in the city since 1963. “We’ve gone through decades of councils, some that are business-friendly and some that make it a little more challenging. Companies are aware that there are challenges associated here, but a lot of municipalities have challenges associated with that, especially those where it’s a favorable place to work, which Boulder is.

“Affordable housing is not anything new, and always is a hot topic for candidates to run on or discuss,” she said. “I don’t think it’s a secret they’d like to see some additional workforce housing options.”

By August, the Boulder Planning board had recommended ending the development moratorium. Some in the business and development communities liked that idea, but not the proposed series of changes to the regulations that guide land use in Boulder that became linked to the repeal.

The proposed new land-use regulations would limit office uses to no more than 25 percent of a building’s floor area unless onsite affordable housing is included, would block construction of additional offices in some largely residential areas where office space already is abundant, and would increase scrutiny of developments that didn’t fit within that newly defined scope through the city’s non-conforming use review process, potentially slowing or stalling projects.

The proposal was up for second reading Sept. 3, but after three hours of discussion, debate and public comment from residents, affordable-housing advocates and members of the business community, the council sent the related ordinances back to staff for additional review until a session scheduled for early October.

“One of the big concerns we are hearing about is small business and the potential loss of those businesses,” Councilwoman Mary Young said during the Sept. 3 meeting. Boulder Chamber public affairs director Andrea Meneghel praised the work of council members and city planning staff but added, “We understand what you want to do, but we aren’t sure if this is the way to go about it.”

The chamber published figures estimating that the more restrictive land use tables could affect properties citywide, not just those properties within the Opportunity Zone. That figure refers to the total number of parcels within zoning districts that would be substantively changed by new city regulations.

“It’s pretty draconian,” Tayer said. “The initial proposal would have said any business expanding by 10 percent or any office building would have to go through use review. Many thousands of businesses would have been impacted by that regulation. It’s clear they weren’t sensitive to the time such a review process takes and many thousands of dollars businesses would have to invest in use-review applications, all with uncertainty that they would be approved.

“City Council heard the concerns and asked staff to go back to the drawing board and take another crack at it,” he said. “We’re awaiting the revised recommendations from staff but at the same time proposing a different approach.”

Tayer urged the city instead to “start to approach the business community in a collaborative way to urge incentives that would motivate businesses and commercial property owners to transition to residential development.

“Scarcity increases demand,” Tayer said, “and the consequence is that prices and rent rates rise. It makes it more burdensome on small businesses and entrepreneurs as they try to find a foothold in our community.”

Gamble said she agrees but also sees the controversy as the nature of the beast in Boulder.

“I think it has some landlords and developers concerned,” she said, “but companies that were concerned about their ability to grow in Boulder — that existed before this, and companies considering Boulder certainly will keep close tabs on the political climate and what’s been set forth by this council. There could be a new direction in a few more months. We just don’t know.”

Techstars’ Zola acknowledged the challenges, but said he believed they can be overcome by the overwhelming energy of Boulder’s entrepreneurial environment, especially for startups.

“When you can’t compete on benefits or perks or pay, you’re offering early equity opportunities,” he said, “the opportunity to make a difference and be a part of something from the beginning.

“A lot of people work in big companies, but there are layers of people working ahead of you doing the work you want to do. At a startup, you can do the work of your boss’s boss’s boss on Day 1.

“Obviously, the nice payout if you can change the world is motivating.”

BizWest staff writer Lucas High contributed to this report.

BOULDER — They all want to be here. But how can they all fit in?

Boulder draws some of the nation’s most dynamic and successful companies, thanks to its quality of life and its concentration of capital — both human and monetary. While technology giants such as Google, Amazon and Twitter continue to expand, the lure of daring venture capitalists and a wealth of resources draws budding entrepreneurs hoping to change their part of the world.

But how well can the big players and the new kids on the block coexist? With commercial space finite, affordable…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!