Far from the funding crowd

Designed to help companies grow, state law has yet to fulfill promise

Ray Burrasca spits out three initials to describe the Colorado Crowdfunding Act, the state’s year-old equity-crowdfunding law that has yet to fund a single company: DOA.

“As far as I know, the state crowdfunding act was dead on arrival,” said Burrasca, founder and organizer of Colorado Crowdfunding, a group promoting crowdfunding in the state, but who opposed the design of the new law.

Burrasca, who also serves as managing director for Windom Peaks Capital LLC, an investment-banking and financial-services advisory firm, described the act as “defectively designed,” partly because it created no secondary market or exchange for sale of the securities, which he considered a critical flaw.

SPONSORED CONTENT

Exploring & expressing grief

Support groups and events, as well as creative therapies and professional counseling, are all ways in which Pathways supports individuals dealing with grief and loss.

“When I discovered what they were up to, I actually started to lobby people at the state against the legislation,” he said. “There is no activity under the state crowdfunding act, nor platforms that are active under the state crowdfunding act,”

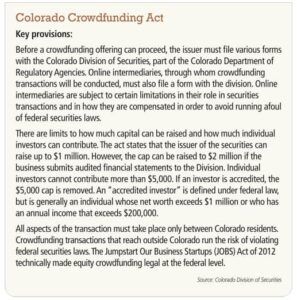

The Colorado Crowdfunding Act was signed into law by Gov. John Hickenlooper in April 2015. It allows crowdfunding efforts “through which investors can acquire debt or equity interests in a prospective company lawful in the State of Colorado,” according to the Equity Crowdfunding page of the Colorado Division of Securities website.

Key to the measure are online intermediaries, essentially websites through which equity can be raised. Five companies initially filed with the Division of Securities to facilitate equity crowdfunding, including:

• Colorado Equity Crowdfunding:

coloradoequitycrowdfunding.com

• EquityEats Inc.:

• EzyXchange Ltd.:

• MassVenture CO Inc.:

• Invest Local LLC.:

One of those websites, coloradoequitycrowdfunding.com, redirects to a GoDaddy landing page, and others have failed to become fully operational.

“There have not been any offerings yet conducted through any online intermediaries,” said Colorado Securities Commissioner Gerald Rome.

He said there have been “problems with online intermediaries getting up and running,” and the state has been working with some of them to “help out on the issues.

“I think that’s where the bottleneck is right now,” Rome said.

One of the issues with the law has been escrow requirements that have proved difficult for the intermediaries, Rome said. An amendment to the Colorado Crowdfunding Act passed during the 2016 legislative session seeks to clarify certain escrow provisions.

“Escrow is still somewhat problematic, finding financial institutions that are willing to do that,” Rome said. “That’s one of the hurdles that are out there.”

Karl Dakin, owner of Dakin Capital Services LLC and a BizWest columnist, who supported the Colorado Crowdfunding Act, said it has several issues that need to be addressed, including the escrow provision.

“I intend to seek a modification of the Colorado Crowdfunding Act to remove the mandatory requirement for the use of an escrow agent and make the requirement discretionary with the Colorado Division of Securities,” he said. “This is the current structure under the Colorado Limited Registration offering, and I believe that is a workable solution.”

Rome said software has been one issue for the intermediaries, which might have to accommodate 100 or even a couple hundred investors.

“That kind of software is expensive,” he said, adding that it’s “a barrier for some of the intermediaries.”

Dakin agreed. One of his companies is Invest Local LLC — one of the intermediaries registered with the state and co-owned by Dakin, Dan Taylor and Lucas Marquardt.

“Discussions with local software developers led to estimates for developing a platform beginning at $350,000 and higher,” he said, adding that of the platforms that already met the regulatory and technical requirements, “none wanted to divert their attention from their existing business plan to enter the market in Colorado.”

Invest Local in October contracted with a startup company that had intended to bundle its software company with a payment processor/escrow agent. However, that agent was not authorized to do business in Colorado, Dakin noted.

Invest Local since has entered into a “white-label” license with CrowdForce, based in San Diego, to provide “a customized platform to meet Colorado regulations and specific requirements,”

Dakin said Invest Local expects to be operational by Aug. 1.

Dakin sees another problem with the Act as written.

“I also intend to seek modification of the minimum capital goal,” he said. “The Colorado Crowdfunding Act currently sets the goal at 50 percent of the maximum capital goal. This threshold fails to recognize that many businesses can make good use of investment dollars less than the minimum capital goal. The goal should be related to the business plan and ability to generate revenue and not set by formula.”

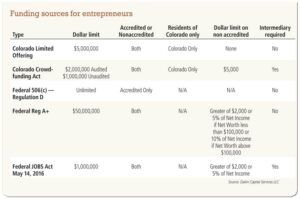

Other options available

But, practical problems with requirements of the act aside, other factors might be restraining use of the new law, Rome said.

But, practical problems with requirements of the act aside, other factors might be restraining use of the new law, Rome said.

In addition to issues with intermediaries, software and escrow, Rome said, some entrepreneurs might have delayed using the Colorado Crowdfunding Act in order to instead explore the federal crowdfunding provisions of the Jumpstart our Business Startups — or JOBS — Act.

Additionally, entrepreneurs have other options for raising funds, including Regulation D offerings, direct public offerings and other structures.

Colorado allows direct public offerings, whereby securities can be registered and sold publicly. One company — and so far the only company — to have used the structure in the past five years is My Trail Co., headed by Demetri Coupounas.

Coupounas said MyTrail was not only the first company to use a DPO in five years but “the first ever online.”

He noted that My Trail currently has two offerings that are open. One is the DPO in Colorado, and the other is under Title III of the JOBS Act.

The DPO so far has raised more than $470,000, he said, while the federal offering has raised $120,000, with another $20,000 in the pipeline. Both contain identical presentations, he said.

“I like them both very much in that they both allow you to present what you have to present to the public,” he said. “They both have good and appropriate requirements about information that is shared with the public.”

Regarding the DPO, Coupounas said, “I was truly impressed with how Colorado was making you do everything that you ought to do.”

Regarding Title III of the JOBS Act, he said, “That whole process also is similarly solid and rigorous in the information that you have to present. It’s a good process that is not only allowing new, small enterprises to raise capital broadly but is properly protecting the public from not having good information on which to base one’s decisions.”

What part is working?

Coupounas said one key difference between the DPO and federal crowdfunding is that, with the DPO, once you pass the threshold for what the minimum raise is, funding is immediate. With Title III, which My Trail offers through the Wefunder.com website, funds are not immediate.

He added that he undertook the federal crowdfunding because it offered an easy opportunity to reach investors from outside Colorado.

“Title III is working,” Coupounas said. “It’s up and it’s functioning, and it’s funding companies.”

He said that critics should not be too quick to discount the effectiveness of the Colorado Crowdfunding Act after just a year. He noted that the state law he has used — the direct public offering — hadn’t had a funding in five years.

“This is an innovative, fast-moving area of finance and business,” Coupounas said, referring to various forms of equity crowdfunding. “I’d be very cautious to say what vectors are going to work and which are not … fine tune and fix whatever isn’t working.”

Rep. Dan Pabon, D-Denver, a key sponsor of the Colorado Crowdfunding Act, said he understands that four or five fundings are in the pipeline under the law, including restaurant opportunities and “an organic grocery-store model in Westminster.”

He added that a good economy in Colorado means interest rates are low and that capital is fairly cheap and available, providing entrepreneurs with other options. Plus, he said, investors have many other options in terms of where to put their money.

But, he said, if fundings under the Colorado Crowdfunding Act continue at their current non-existent pace, it soon might be time to revisit the law.

“I think it’s a little premature, but if another quarter or two go by and no activities happen, it’s worth talking to the securities community and the investor community and find out what’s keeping you from using this opportunity,” Pabon said.

For his part, Rome said he thinks there’s still a role for the Colorado Crowdfunding Act.

“I think so,” he said. “It’s always been our position that when you’re raising money, $500,000, a million dollars, it really is going to be a local effort.”

He said that a brewery in Boulder or Denver, for example, would find that “the interest in your company is going to come from the Denver-Boulder area. It’s going to come from your customers. In essence, to have some sort of regulatory oversight of that, it makes much more sense to do it on a local basis, rather than a federal basis.”

“We know that there are small businesses out there who are anxious and willing to try and raise money through Colorado Crowdfunding,” Rome added. “We’re still engaged with that community in trying to work through some of those issues and trying to make it happen.”

Christopher Wood can be reached at 303-630-1942, 970-232-3133 or cwood@bizwestmedia.com.

Ray Burrasca spits out three initials to describe the Colorado Crowdfunding Act, the state’s year-old equity-crowdfunding law that has yet to fund a single company: DOA.

“As far as I know, the…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!