As salaries increased, students picked up the tab

Special Report: Payday on Campus

Federal loan pools helping fuel cost of higher education

FORT COLLINS — Colorado State University sophomore Courtney Wilson has racked up $56,000 in debt in her pursuit of a bachelor’s degree.

The sophomore from Lomita, Calif., a Los Angeles suburb, has had to work two jobs: one in retail 10 hours each week, and another one as a campus laboratory assistant for 18 hours each week. Wilson works most mornings, has classes in the afternoon and does schoolwork at night: She doesn’t have much of a social life, she said.

After she graduates, Wilson, a psychology major, plans to join the U.S. Air Force, in part to help pay off her loans. She hopes her parents will help her repay what the military cannot cover. For now, she devotes a portion of her paychecks to make small payments on loan interest.

SPONSORED CONTENT

How Platte River Power Authority is accelerating its energy transition

Platte River Power Authority, the community-owned wholesale electricity provider for Northern Colorado, has a history of bold initiatives.

“That’s really all I can afford to pay off,” Wilson said.

Administrative aid

In recent years, large pools of federal loan money and financial aid have helped fuel the rising cost of higher education. Students have had greater access to financial aid and loans, giving universities greater latitude to increase tuition, said Richard Vedder, an economics professor at Ohio University and director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity in Washington, D.C.

The federal student loan program has expanded dramatically, offering assistance to middle-income students as well as students from low-income households, Vedder said.

Special Report: Campus payrolls defy recession. Full story.

The government lent students more than $100 billion for the 2011-2012 school year, more than doubling the amount lent a decade earlier, the Chronicle of Higher Education reported.

“The federal student loan program has become more generous in terms of the magnitude of money handed out,” Vedder said. “The ability of the kids to get their hands on money, one way or the other, has allowed the colleges to be more aggressive in raising their tuition and fees.”

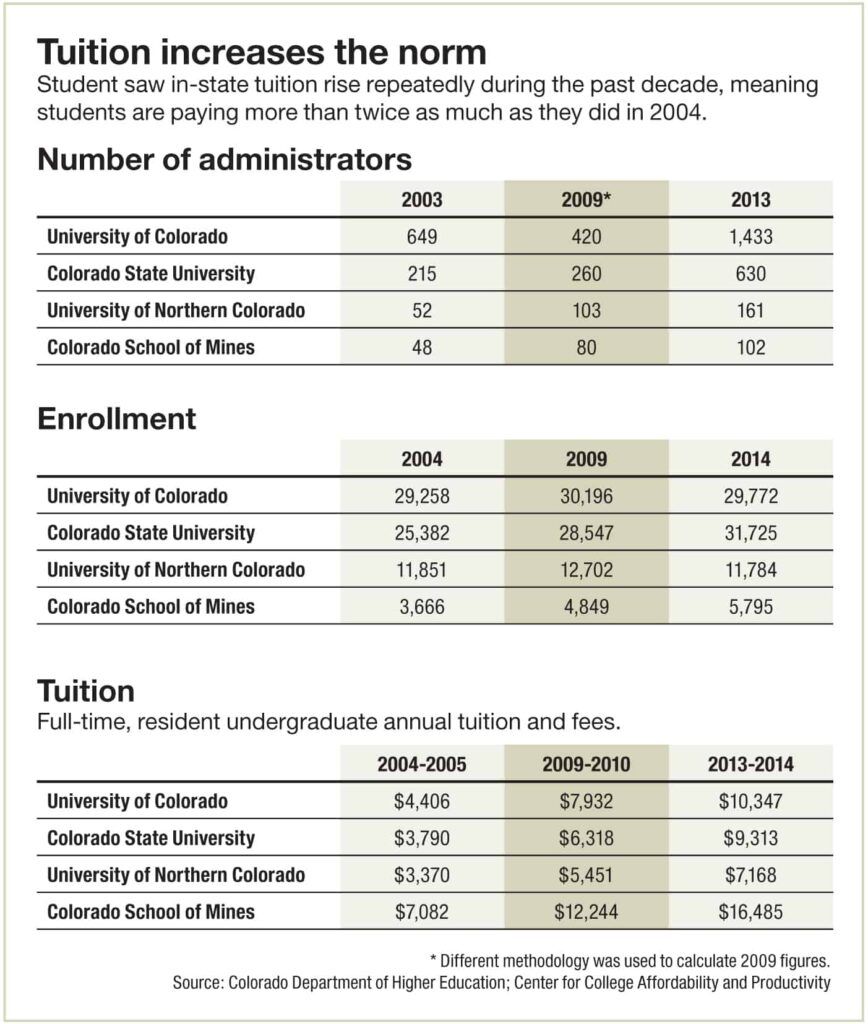

Data from the Colorado Department of Higher Education illustrates the trend.

• At the University of Colorado, financial aid soared to $380.2 million in 2013, up from $157 million in 2003.

• Students in the Colorado State University system received $201.7 million in 2013, vs. $94.9 million in 2004.

• University of Northern Colorado students received $75.3 million in financial aid in 2013, up from $34.4 million in 2004.

• At Colorado School of Mines, financial aid has increased to $60 million from $12.7 million during the same period.

“The schools have accumulated more cash, and they’ve used that cash rather richly on themselves on more staff and higher pay,” Vedder said.

In 2000, the state funded 68 percent of a student’s cost of college, while students paid 32 percent, according to a report by the Colorado Department of Higher Education. By 2010, the state funded just 32 percent, increasing students’ share to 68 percent.

“It’s almost a direct correlation to the decline in state appropriation,” said Diane Duffy, chief financial officer for the higher-education department. “State funds have gone down, tuitions have gone up to fill the gap.”

Student debt skyrockets

Those tuition bills are being financed with $1.2 trillion in U.S. student debt. President Obama has called the situation “a crisis in terms of college affordability and student debt” while others have voiced concern that the mounting debt will trigger another financial collapse.

In the past five years, the state has reduced funding for higher education from $706 million to $513 million, a decrease of 27 percent in total dollars. The reduction in funding per resident student has dropped even more, by 36 percent.

Resident tuition remains about average compared with other states, according to the Department of Higher Education report. Still, Colorado has the 16th-highest student-loan default rate of U.S. states and territories, at 15.3 percent.

“After years of declining public investment in the infrastructure and operations of higher education, the goal of maintaining high-quality, accessible and affordable higher education opportunities for Coloradans is at risk,” reads the report.

In 2010, when the Legislature gave university governing boards the flexibility to set tuition rates, a series of rapid annual increases in tuition ensued, according to the Department of Higher Education. The policy will expire during the 2015-16 fiscal year. Lawmakers meanwhile have capped tuition increases at 6 percent for the next two years while increasing higher education funding by $100 million, according to the Colorado Statesman.

Tuition up 100 percent

Meanwhile, tuition has more than doubled at each of Colorado’s major research universities during the past 10 years.

Even as tuition has soared, Vedder disputes the common argument made by universities that administrators need higher pay to deal with increasingly complicated operations spurred by higher enrollment.

“The administrative chores of running a university haven’t changed dramatically,” he said.

While some officials say the higher administrative demands have occurred because of rising enrollments, the data indicate that not all schools have seen dramatic growth in the size of their student bodies.

• At UNC, enrollment actually has declined slightly to 11,800 students from about 11,900 in 2004.

• At CU-Boulder, enrollment has risen by just 500 students over the past 10 years, to 29,800 from 29,300.

• CSU in Fort Collins saw the highest volume of enrollment of more than 6,300 students in the past 10 years. Enrollment grew to 31,700 from 25,400, a 25 percent increase.

• Colorado School of Mines has seen the highest percentage increase in enrollment, which rose to 5,800 in 2014 from 3,700 in 2004, a nearly 60 percent jump.

At CSU, enrollment has grown at a compound annual rate of slightly more than 2 percent, while undergraduate resident tuition and fees have grown at a compound annual growth rate of more than 9 percent, reaching $9,300 during the 2013-14 school year, up from $3,800 during the 2004-05 school year.

Wilson, the CSU student, already has received $10,000 in loans from Nelnet, a federal student loan provider, and the remaining $46,000 in bank loans through Discover Student Loans. A portion of those loans will fund the $26,000 cost of attending CSU as an out-of-state student this year.

Rock star administrators?

Wilson knows that a portion of her tuition funds the salaries of high-paid administrators such as CSU President Tony Frank.

“I don’t understand why he is such a big deal,” Wilson said.

Lt. Gov. Joe Garcia, executive director of the Colorado Department of Higher Education, said the higher-education department is doing an analysis to better convey to the public and policy makers what factors determine the cost of educating a student and prices charged to students.

“Certainly, no question, there’s been growth in terms of overall dollars spent for salaries for some high-level folks within Colorado’s public institutions of higher education,” he said. “I think the important thing to keep in mind here is whether it’s competitive with other state institutions of higher education throughout the country.”

The top administrators’ salaries account for a fraction of 1 percent of the budgets of Colorado’s public institutions, but their pay remains important on a symbolic level, Garcia said.

“We are saying to the public that we want to keep costs low for students,” he said. “And people naturally look to the salaries of the highest-paid administrators and say, ‘Well, is this a responsible way to spend that money?’ That’s a fair question.”

Steve Lynn can be reached at 970-232-3147, 303-630-1968 or slynn@bizwestmedia.com. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveLynnBW.

Special Report: Payday on Campus

Federal loan pools helping fuel cost of higher education

FORT COLLINS — Colorado State University sophomore Courtney Wilson has racked up $56,000 in debt in her pursuit of a bachelor’s degree.

The sophomore from Lomita, Calif., a Los Angeles suburb, has had to work two jobs: one in retail 10 hours each week, and another one as a campus laboratory assistant for 18 hours each week. Wilson works most mornings, has classes in the afternoon and does schoolwork at night: She doesn’t have much of a social life, she said.

After she…

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!