Focus sharpens on end-of-life decisions

FORT COLLINS — Conversations between doctors and patients about planning for death could become more prominent in Colorado hospitals if the federal government goes forward with Medicare reimbursements next year.

End-of-life planning has generated controversy in the past, with opponents of the Affordable Care Act claiming the practice was akin to the use of “death panels.” The planning sessions, however, have gained more prominence at health facilities statewide as hospitals seek to improve patient outcomes, save money and reduce stress for doctors and nurses trying to assess what kind of care an unresponsive person might have wanted.

SPONSORED CONTENT

How Platte River Power Authority is accelerating its energy transition

Platte River Power Authority, the community-owned wholesale electricity provider for Northern Colorado, has a history of bold initiatives.

Medicaid, the program that serves the poor, as well as private insurance companies already reimburse health-care providers for end-of-life planning. But if Medicare moves forward with the practice, it will mean that millions of elderly people who are most likely to need this assistance will receive it.

As of July 2012, 686,012 people in Colorado were enrolled in Medicare.

Everyone from patients with terminal cancer to younger persons who might die in a car crash could benefit from such assistance. The outcome of the discussions can range from wanting to die at home to not wanting a feeding tube. Such plans help determine who makes the decision about when a loved one should be placed on life support or taken off.

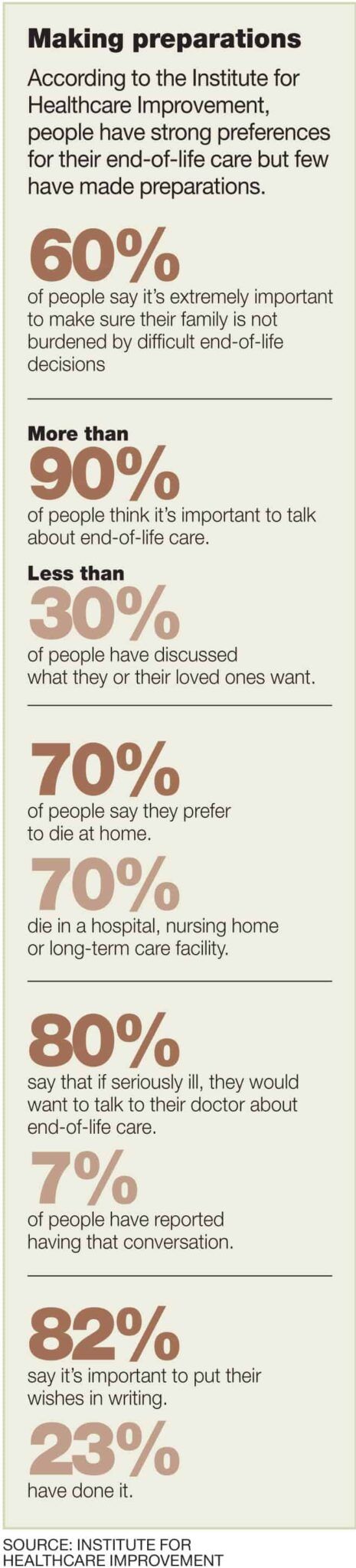

Most people say they would prefer to die at home, said Dr. JP Valin, chief medical officer for Banner Health. Most patients, however, end up dying in a hospital because of a lack of end-of-life planning.

“Somehow, there’s a disconnect between what people say they want and what actually happens,” he said.

If more conversations between patients and doctors took place, he said, people would get their wishes more often.

“We would be more likely to understand, meet and honor the wishes of patients if we had those discussion earlier,” he said. “Sometimes, it’s very difficult when the patient never talked to anyone in their family, their loved ones, their children, their spouse, as to what their wishes and desires were.”

Each year, the American Medical Association provides the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services with revisions to a coding system that is used to price thousands of physician services. In a typical year, hundreds of codes are added, revised or deleted.

This year, advanced-care planning was among the codes sent to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which will decide whether or not to include it in the coding system.

Such advanced-planning services already are reimbursed on a state level through Medicaid: $40 for a 30-minute consultation just once annually based on a law passed by the Legislature last year. While they already offer end-of-life planning in a variety of forms, health care providers hope they can go further when they are reimbursed for end-of-life planning through Medicare.

Banner Health handles end-of-life planning by incorporating conversations between doctors and patients along with regular health-care services. But if Banner Health received reimbursements for end-of-life conversations, patients could schedule appointments where they could devote greater attention to end-of-life planning, Valin said.

“In the future, if Medicare were to reimburse for these, that may encourage more patients to come in and have a dedicated visit exclusively for advance-care planning,” he said. “Today, those discussions typically occur as part of a regularly scheduled visit.”

Last year, University of Colorado Health started an inpatient palliative medicine consult service at Poudre Valley Hospital that serves people with life-threatening conditions. A staff of two has seen more than 300 patients, old and young, with a variety of diagnoses since the service began in August 2013.

The same kinds of programs have proliferated throughout the nation despite the lack of reimbursement by Medicare, said Lisabeth Paradise, a nurse practitioner board-certified in hospice and palliative medicine. In fact, private insurers are reimbursing hospitals for the conversations because they understand the value of preventing unnecessary or prolonged hospitalizations.

“It keeps the patients’ voice at the table, which I think is invaluable for families,” Paradise said. “It gives patients control: It gives them knowledge that their wishes will be followed and that their loved ones won’t be in a position to have to decide on their behalf.”

UCHealth also participates in the Conversation Project, which encourages conversations between family members about end-of-life planning. The program provides tips for people on how to have the discussions with loved ones.

Dr. Dan Johnson, physician lead for palliative-care innovation and development for Kaiser Permanente, said the end-of-life conversations through the health provider and insurer have taken place regularly for years.

“What we’re seeing is much more attention around how important these conversations are,” he said.

Kaiser Permanente has learned that doctors and patients need to have more than one of these kinds of discussions to help match care with people’s desires. Kaiser Permanente has just started training other employees besides doctors, such as nurses and social workers, on how to build the conversations into usual care.

“It starts to allow us to develop the relationships that will help us in the decision-making process,” Johnson said. “We want to make sure that the care we’re delivering is personalized, recognizing that people with the same illness may respond differently and want different things depending on what their goals and values are.”

While Medicaid reimbursements are given for end-of-life planning, Medicare reimbursement would represent a positive step for services that Kaiser and others already deliver. At the same time, Johnson said he would not want to see any policy that requires people to do end-of-life planning, as some patients may not be ready to form a plan.

Not all health professionals agree on that facet of end-of-life planning. Banner Health chief executive Peter Fine thinks lawmakers should require people to submit a living will and medical power of attorney in their Medicare applications.

“There might be concern among some about the appropriateness of government involvement in making this intensely personal matter a requirement of applying for Medicare benefits,” Fine wrote recently in Becker’s Hospital Review. “I would ask these people to consider the fact that the completion of these documents preserves and strengthens individual choice, keeps the highly personal discussion about dying within the privacy of the family and has the real potential to save tens of billions of dollars.”

Conversation Project

University of Colorado Health holds sessions where people can learn more about how to have discussions with family members about end-of-life planning.

• 5:30 to 7 p.m. Oct. 8, Poudre Valley Hospital, Café F meeting room, 1024 S. Lemay Ave., Fort Collins

• 5 to 6:30 p.m. Oct. 21, Fort Collins Senior Center, 1200 Raintree Drive, Fort Collins

Source: UCHealth

Steve Lynn can be reached at 970-232-3147, 303-630-1968 or slynn@bizwestmedia.com. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveLynnBW.

FORT COLLINS — Conversations between doctors and patients about planning for death could become more prominent in Colorado hospitals if the federal government goes forward with Medicare reimbursements next year.

End-of-life planning has generated controversy in the past, with opponents of the Affordable Care Act claiming the practice was akin to the use of “death panels.” The planning sessions, however, have gained more prominence at health facilities statewide as hospitals seek to improve patient outcomes, save money and reduce stress for doctors and nurses trying to assess what kind of care an unresponsive person might have wanted.

THIS ARTICLE IS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Continue reading for less than $3 per week!

Get a month of award-winning local business news, trends and insights

Access award-winning content today!